Reference: August 2024 | Issue 8 | Vol 10 | Page 20

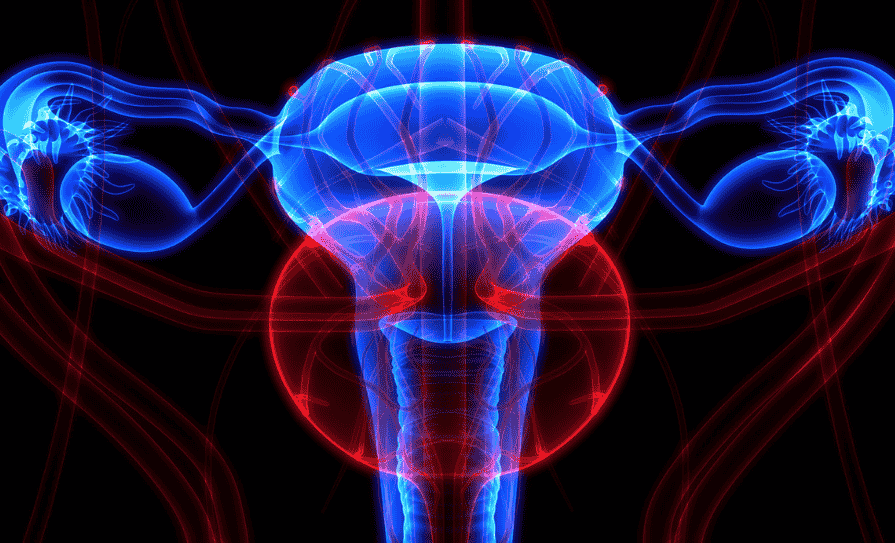

Uterine cancer is a prevalent gynaecological malignancy associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. It primarily includes endometrial carcinoma and the less frequent uterine sarcoma.

Endometrial carcinoma arises from the inner lining of the uterus, while uterine sarcoma develops from the myometrium or supporting connective tissue, each with distinct origins and clinical implications. Endometrial carcinoma is the more prevalent form.

Uterine sarcoma is a rarer and more aggressive form of uterine cancer, characterised by its diverse histological subtypes, and presents with more severe symptoms and a poorer prognosis compared to endometrial carcinoma.1,2

Epidemiology

Endometrial carcinoma accounts for more than 90 per cent of all uterine cancers. The global incidence in 2020 was 417,336. It ranks as the fourth most prevalent malignancy among women in high socioeconomic index countries and the sixth most common cancer in women globally. Most cases occur between 65 and 75 years of age.

Over the past 30 years, the incidence of endometrial carcinoma has surged by 132 per cent worldwide, a trend expected to continue due to the ageing population and rising rates of obesity and diabetes. Despite the growing number of women diagnosed with endometrial cancer, mortality rates are declining due to recent advancements in early diagnosis and treatment.1,2

Globally, uterine cancer is a significant health concern. In the US, it is the fourth most common cancer in women, with an estimated 67,880 new cases and 13,250 deaths in 2024.3 In Europe, the incidence of uterine cancer varies widely.

According to the European Cancer Information System, approximately 130,000 new cases are diagnosed annually in Europe, with the highest rates observed in Eastern and Northern Europe.4 The Irish Cancer Society reports about 550 new cases of uterine cancer each year, with a notable increase in incidence over the past decade.5

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of uterine cancer, primarily endometrial carcinoma, involves a combination of genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors that lead to abnormal cell growth in the lining of the uterus. Genetic alterations such as PTEN mutations, commonly found in endometrial cancers, result in unregulated cell growth through the PI3K/AKT pathway.

Other genetic mutations, including those in PIK3CA and KRAS, enhance cell proliferation and survival via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and RAS/MAPK pathways, respectively. Microsatellite instability (MSI), caused by defects in the DNA mismatch repair system and often associated with Lynch syndrome, contributes to the cancer’s development. High-grade endometrial cancers frequently exhibit p53 mutations, causing genomic instability and tumour progression.6

Hormonal influences play a significant role in uterine cancer pathophysiology. Unopposed oestrogen promotes endometrial proliferation, increasing cancer risk, particularly in the absence of balancing progesterone. A deficiency in progesterone results in increased susceptibility to endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma.

Environmental and lifestyle factors such as obesity, which leads to higher oestrogen levels from the conversion of androgens in adipose tissue, also contribute to the risk. Diabetes and hypertension are associated with higher cancer risk due to shared metabolic factors, and extended exposure to oestrogen due to early menarche and late menopause further elevates this risk.6

In the tumour microenvironment, cancer cells evade immune detection by upregulating checkpoint molecules like programmed cell death protein (PD-1) and its ligand PD-L1. Tumours also stimulate angiogenesis to sustain growth and metastasis. Understanding these mechanisms is important for developing targeted therapies and improving patient outcomes.6

Risk factors

Key risk factors for uterine cancer include advancing age, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, unopposed oestrogen exposure, and genetic predisposition. Excess adipose tissue in obesity leads to increased oestrogen levels unopposed by progesterone, promoting endometrial proliferation. Both diabetes and hypertension are associated with a higher risk of endometrial cancer.

Unopposed oestrogen exposure, which can occur due to hormone replacement therapy, tamoxifen use, or conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome, further elevates this risk. Additionally, a genetic predisposition, notably Lynch syndrome, significantly increases the likelihood of developing uterine cancer.6,7,8,9

Protective factors

Protective factors for uterine cancer include the use of combined oral contraceptives, maintaining a healthy weight, regular physical activity, and having full-term pregnancies. Combined oral contraceptives provide significant protection by balancing oestrogen with progestin, thereby reducing the risk of endometrial hyperplasia.

Maintaining a healthy weight helps prevent the excess adipose tissue that leads to increased oestrogen levels, which are not counterbalanced by progesterone. Regular physical activity contributes to overall hormonal balance and reduces obesity.

Full-term pregnancies lower the risk, as this interrupts the prolonged exposure of the endometrium to oestrogen by introducing periods of progesterone dominance during pregnancy. Breastfeeding also contributes to this protective effect by delaying the return of regular ovulation and menstrual cycles, thereby reducing the cumulative exposure to oestrogen.

Some studies suggest that coffee may have a protective effect against uterine cancer, but further research is required to fully understand the potential benefit.9,10

Clinical presentation

Uterine cancer, predominately endometrial cancer, often presents with abnormal vaginal bleeding, which is the most common symptom. This can include postmenopausal bleeding, bleeding between periods, and unusually heavy menstrual cycles.

Other symptoms include watery or blood-tinged vaginal discharge, persistent pelvic pain, discomfort during intercourse, unexplained weight loss, frequent or painful urination, and chronic fatigue. Some women may also notice pain or a mass in the abdomen and experience symptoms of anaemia, such as fatigue and shortness of breath, due to chronic blood loss.

Recognising these symptoms early is important, especially for those at higher risk due to factors like obesity, hormonal imbalances, increased age, and family history.6,11

Evaluation and diagnosis

Initial evaluation involves a detailed medical history, physical examination, and pelvic ultrasound. Endometrial biopsy is essential for histopathological diagnosis.6,11

A comprehensive medical history, including the patient’s personal and family medical history, menstrual patterns, and any relevant symptoms such as abnormal bleeding or pelvic pain, is carried out.

The physical examination focuses on the patient’s general health and a thorough pelvic exam assesses the size, shape, and any abnormalities of the uterus and surrounding structures.6,11

A pelvic ultrasound is conducted to visualise the uterine structure, assess endometrial thickness, and detect any potential masses or abnormalities. To confirm the diagnosis, an endometrial biopsy is necessary for histopathological analysis to identify cancerous cells and determine the presence, type, and grade of the cancer.

If necessary, additional tests such as a Sono hysterography or hysteroscopy may be carried out to further evaluate the uterine cavity. Imaging studies like CT scans or MRIs may also be used to determine the extent of cancer spread and assist in staging.6,11

Staging

The staging of uterine cancer, particularly endometrial cancer, follows the guidelines provided by the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO). The staging is based on the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) system, which is widely used for gynaecological cancers. The most recent guidelines outline the following stages:11,12,13

- Stage I: The tumour is confined to

- the uterus.

- Stage IA: The cancer is confined to the endometrium or invades less than halfway through the myometrium.

- Stage IB: The cancer invades more than halfway through the myometrium.

- Stage II: The tumour invades the cervical stroma but does not extend beyond the uterus.

- Stage III: Local and regional spread

- of the tumour.

- Stage IIIA: The cancer invades the serosa and/or the adnexa (ovaries or fallopian tubes).

- Stage IIIB: The cancer invades the vagina or the parametrium.

- Stage IIIC: The cancer spreads to pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodes.

- Stage IIIC1: Involvement of pelvic lymph nodes.

- Stage IIIC2: Involvement of para-aortic lymph nodes with or without pelvic lymph node involvement.

- Stage IV: The tumour invades the bladder and/or bowel mucosa, and/or distant metastasis.

- Stage IVA: The cancer invades the bladder and/or bowel mucosa.

- Stage IVB: The cancer has spread to distant organs, including intra-abdominal and/or inguinal lymph nodes

These stages help in determining the extent of the disease and guide treatment planning. The staging process typically involves a combination of physical examination, imaging studies, and biopsy or surgical findings.

The FIGO system’s detailed categorisation allows for precise identification of cancer spread, which is important for choosing the most appropriate therapeutic approach and assessing prognosis.11,12,13

Treatment

The treatment options for uterine cancer, particularly endometrial cancer, are diverse and depend on the stage and grade of the cancer, as well as the patient’s overall health and personal preferences. The main treatment modalities include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and targeted therapy.

The treatment of uterine cancer involves a multidisciplinary team, including gynaecologic oncologists, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, and supportive care specialists. This approach ensures that patients receive comprehensive care tailored to their specific needs.6,11,14

Treatment by stage

Stage I: Surgery – total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) is usually sufficient. Depending on the tumour grade and invasion depth, adjuvant radiation therapy or hormone therapy may be considered.11

Stage II: Radical hysterectomy with BSO and lymphadenectomy is common. Adjuvant radiation therapy and, in some cases, chemotherapy may follow.11

Stage III: A combination of surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy is typically used. Surgery aims to remove as much cancer as possible, followed by adjuvant therapies.11

Stage IV: Treatment focuses on palliative care to relieve symptoms and improve quality-of-life. Options include a combination of surgery, if feasible, radiation, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and targeted therapy.11

Surgery

Surgery remains the cornerstone of treatment for early-stage uterine cancer. Standard procedures include a total hysterectomy with BSO. Lymph node dissection or sentinel lymph node mapping may also be performed to ensure accurate staging.

The specific type of surgery depends on the cancer’s stage and the patient’s overall health. A total hysterectomy involves the removal of the uterus and cervix and is often performed via abdominal, vaginal, or laparoscopic methods. BSO involves the removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes, usually done in conjunction with a hysterectomy.

Lymphadenectomy is performed to remove lymph nodes in the pelvis and para-aortic area to assess the spread of cancer. In more advanced stages where the cancer has spread beyond the uterus, a radical hysterectomy is used, which involves removing the uterus, surrounding tissues, and the upper part of the vagina.6,11,14

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy rays to kill cancer cells and can be used either as the main treatment or as adjuvant therapy after surgery. External beam radiation therapy targets the tumour from outside the body and is commonly used for more advanced stages of cancer or to shrink tumours before surgery.

Brachytherapy involves delivering internal radiation directly to the tumour site through radioactive seeds or cylinders placed inside the vagina and is often used for early-stage cancers or as adjuvant therapy.6,11,14

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to destroy cancer cells and is typically used for advanced or recurrent uterine cancer. It may be administered either before or after surgery. Common chemotherapy drugs include doxorubicin, cisplatin, carboplatin, and paclitaxel. Often, combination chemotherapy is used to enhance the treatment’s effectiveness.6,11,14

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy is used to treat cancers that are hormone receptor-positive, especially when surgery or radiation are not suitable options. Progestins, such as medroxyprogesterone acetate and megestrol acetate, are synthetic progesterone-like drugs that slow the growth of endometrial cancer cells.

Aromatase inhibitors, including letrozole and anastrozole, work by reducing oestrogen levels, which helps to slow the growth of hormone-sensitive cancer cells. Tamoxifen, a selective oestrogen receptor modulator, blocks oestrogen’s effects on endometrial cancer cells.6,11,14

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy focuses on specific molecules involved in cancer growth and progression and is often used for advanced or recurrent uterine cancer. Bevacizumab (avastin) is an example of a targeted therapy; it is an anti-angiogenesis drug that inhibits the growth of blood vessels that supply the tumour.6,11,14

Evolving role of immunotherapy

Immunotherapy has revolutionised the treatment landscape for many cancers, including uterine cancer. It enhances the immune system’s ability to recognise and destroy cancer cells. The primary forms of immunotherapy being explored include immune checkpoint inhibitors, cancer vaccines, and adoptive cell therapy.1,6,14

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, particularly those targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 pathways, have shown promise in the treatment of advanced uterine cancer. One key development is pembrolizumab, a PD-1 inhibitor that has been approved for patients with MSI-high or mismatch repair-deficient (dMMR) endometrial cancer.

The KEYNOTE-158 study demonstrated significant response rates in these patients, leading to its regulatory approval. Additionally, combination therapies have also shown promise; for example, pembrolizumab combined with lenvatinib, a multikinase inhibitor, has demonstrated improved progression-free survival and overall survival in advanced endometrial cancer compared to chemotherapy alone, as shown in the KEYNOTE-775 trial.1,14

Cancer vaccines aim to induce a robust immune response against tumour-specific antigens. Several vaccines targeting overexpressed antigens in uterine cancer are currently under investigation. These include vaccines targeting human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2/neu), which is overexpressed in a subset of uterine cancers, and those targeting p53, a common mutation found in endometrial carcinomas.1,6,14

Adoptive cell therapy involves modifying a patient’s own immune cells to enhance their anti-tumour activity. Strategies being explored include chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, which engineers T-cells to target specific antigens expressed on uterine cancer cells. Another approach is the expansion and activation of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) extracted from tumour tissue.1,6,14

Future directions and challenges

Identifying predictive biomarkers is important for selecting patients who will benefit from immunotherapy. Current research focuses on several areas, including tumour mutational burden (TMB), where high TMB is associated with better responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Specific genetic alterations beyond MSI and PD-L1 expression are also being studied as potential biomarkers.1,15

Combining immunotherapy with other treatments, such as targeted therapy, chemotherapy, and radiation, holds potential for synergistic effects. Key research areas include optimal sequencing and combinations to determine the best strategies and sequences to maximise efficacy and minimise toxicity.1,15 Resistance to immunotherapy poses a significant challenge.

Understanding and overcoming resistance mechanisms involves examining several key factors. Tumour-intrinsic factors include genetic and epigenetic changes within the tumour itself. The immune microenvironment must be modulated to enhance the immune response, and host factors such as the patient’s overall immune status and comorbidities also need to be considered.1,15

The evolving role of immunotherapy in uterine cancer represents a paradigm shift in treatment. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, cancer vaccines, and adoptive cell therapies offer promising new avenues for improving patient outcomes, particularly in advanced and recurrent cases.

Continued research into biomarkers, combination therapies, and resistance mechanisms is important to fully harness the potential of immunotherapy in uterine cancer. Personalised immunotherapeutic approaches, guided by a deeper understanding of tumour immunology, hold the promise of significantly enhancing survival and quality-of-life for patients with this challenging malignancy.

References

- Baker-Rand H, Kitson SJ. Recent advances in endometrial cancer prevention, early diagnosis and treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16(5):1028.

- Makker V, MacKay H, Ray-Coquard I, et al. Endometrial cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):88.

- American Cancer Society [Internet]. Key statistics for endometrial cancer. USA: ACS; 2024. Available at: www.cancer.org/cancer/types/endometrial-cancer/about/key-statistics.html.

- European Cancer Information System [Internet]. Cancer factsheets in EU27 countries – 2020. ECIS; 2024. Available at: https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/factsheets.php.

- Irish Cancer Society [Internet]. Uterine Cancer. ICS; 2024 Available at: www.cancer.ie/cancer-information-and-support/cancer-types/uterine-womb-cancer.

- Mahdy H, Casey MJ, Vadakekut ES, et al. Endometrial Cancer. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Florida: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525981/.

- Aune D, Sen A, Vatten LJ. Hypertension and the risk of endometrial cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44808.

- Diabetes.co.uk. Diabetes complications – uterine cancer. UK: Diabetes.co.uk; 2024. Available at: www.diabetes.co.uk/diabetes-complications/uterine-cancer.html.

- Cancer Research UK. Risks and causes of womb cancer. UK: Cancer Research UK; 2024. Available at: www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/womb-cancer/risks-causes.

- National Cancer Institute. Endometrial Cancer Prevention. US: NCI; 2024. Available at: www.cancer.gov/types/uterine/patient/endometrial-prevention-pdq.

- Oaknin A, Bosse TJ, Creutzberg CL, et al. Endometrial cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2022;33(9):860-877.

- International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. Cancer of the endometrium: 2023 FIGO staging. London: FIGO; 2024. Available at: www.figo.org/news/figo-staging-endometrial-cancer-2023.

- Berek JS, Matias-Guiu X, Creutzberg C, et al. FIGO staging of endometrial cancer: 2023. J Gynecol Oncol. 2023;34(5):e85.

- Kalampokas E, Giannis G, Kalampokas T, et al. Current approaches to the management of patients with endometrial cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(18):4500.

- Hamoud BH, Sima RM, Vacaroiu IA, et al. The evolving landscape of immunotherapy in uterine cancer: A comprehensive review. Life (Basel). 2023;13(7):1502.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.