Reference: June 2024 | Issue 6 | Vol 10 | Page 18

Case study

A 38-year-old male was reviewed in the rheumatology clinic for the first time following a 15-year history of lower back pain and stiffness. He had previously been seen by a spinal team for lower back pain, where no surgical intervention was deemed necessary. He subsequently attended a pain specialist for repeat lumbar medial branch blocks for the previous three years.

He was unable to work and was on disability payment because of chronic pain and difficulty mobilising. Two months prior to rheumatology clinic review, the patient described his first episode of a painful, red, right eye with photophobia and blurred vision, which was subsequently diagnosed as acute anterior uveitis by ophthalmology. Given this diagnosis, the patient was referred to the rheumatology service.

On review in clinic, the patient’s back pain was isolated to the lower back and buttocks without any radiation. It was associated with more than two hours of early morning stiffness and early morning wakening secondary to pain. Pain was responsive to NSAIDs, and these were being used on an as-needed basis.

Pertinent examination findings included spinal measurement showing: Tragus to wall -28 cm (normal range <10cm), intermalleolar distance -106cm (120cm), modified Schober’s -1cm (>7cm), lateral flexion -5cm bilaterally (>20cm), cervical rotation -70 degrees on the right and 50 degrees on the left (>85 degrees), and chest expansion -3cm (>5cm).

Disease activity and functionality scores showed an ASDAS of 4.19, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) of 7.2, and a Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) of 5.8. Joint count showed zero swollen or tender joints and the patient was FABER (Patrick’s test) positive. There were no noted skin or nail changes consistent with psoriasis and no enthesitis or dactylitis. The patient reported no blood or mucous in the stool in recent years.

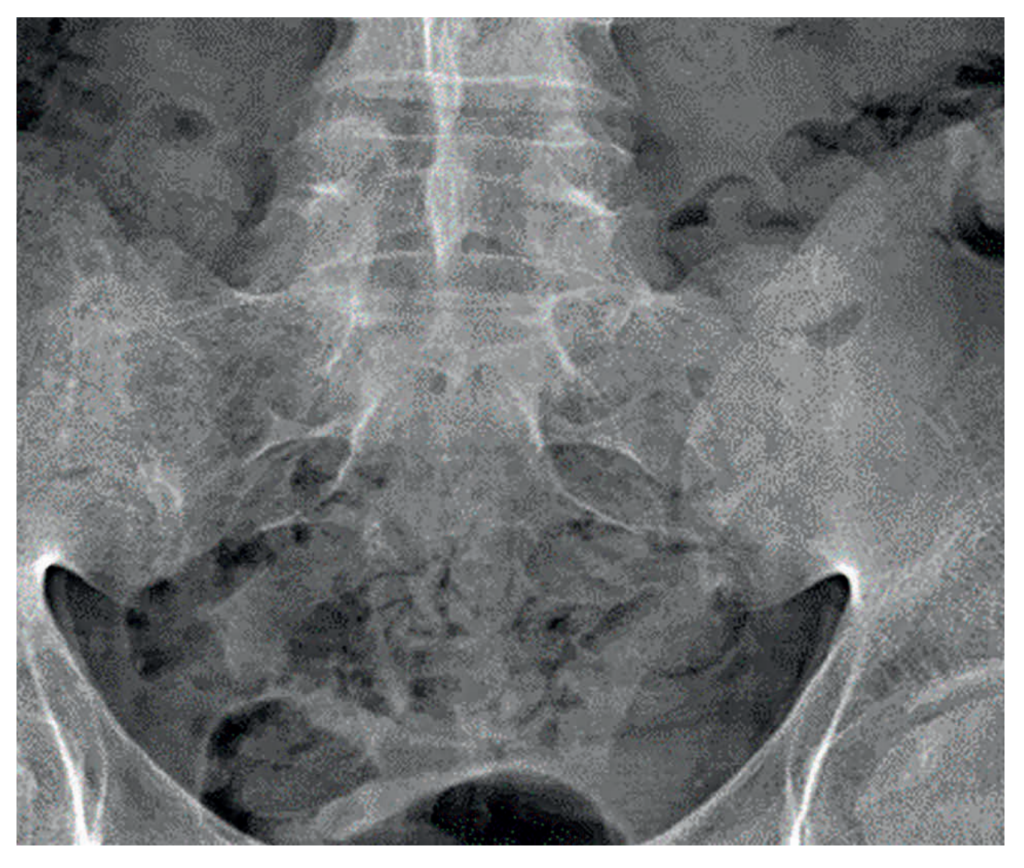

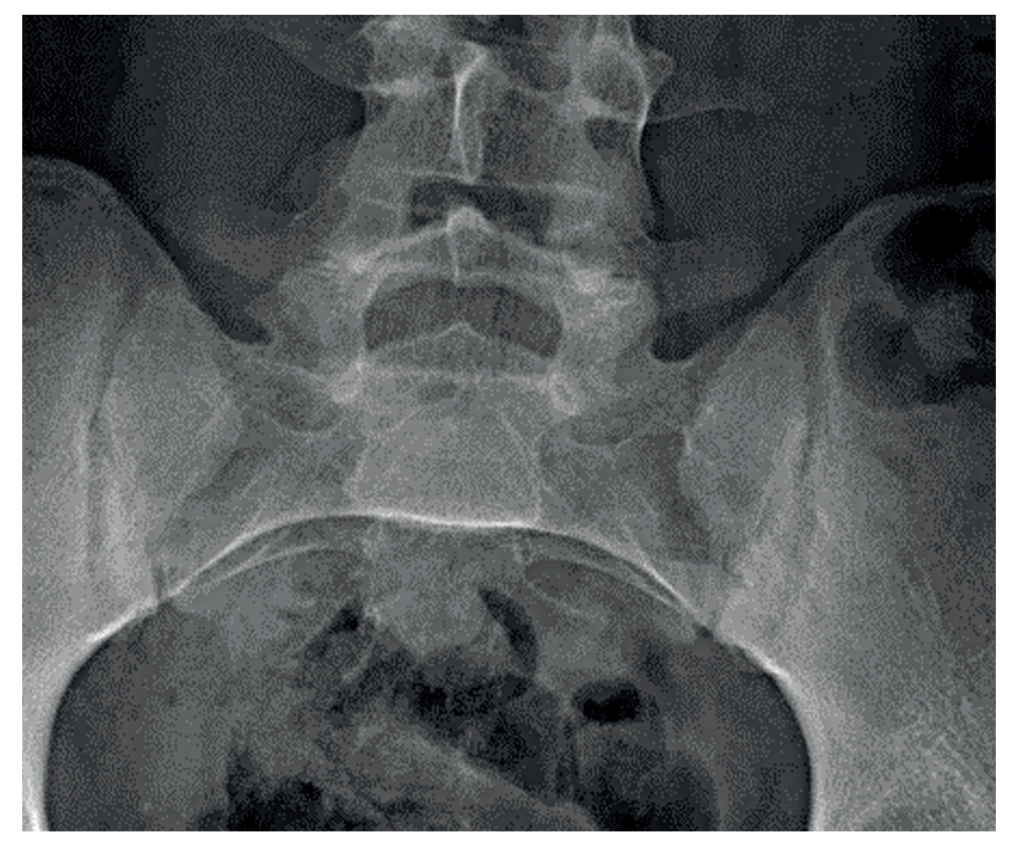

Recent investigations showed normal full blood count, renal and liver profile with a raised CRP of 10mg/L, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 21mm/hr. HLA-B27 was positive. On a review of previous pelvic x-rays, radiographic progression can be seen between 2007 (Figure 1), showing SIJ joint widening, and 2015 (Figure 2), showing SIJ sclerosis and erosions, and 2023 showing bilateral SIJ fusion (Figure 3).

This patient met the ASAS criteria for axSpA, with a greater than three-month history of back pain, being under the age of 45, with definite sacroiliitis on imaging according to the 1984 modified New York criteria for AS, HLA-B27 positivity, uveitis, a good response to NSAIDS, and

a raised CRP.

Given the radiographic changes, raised CRP, and high disease activity score, this patient was commenced on a TNFi in the form of adalimumab 40mg subcutaneously every two weeks. He was reviewed in clinic 12 weeks after commencement. BASMI and BASFI scores remained similar, however, ASDAS score dropped to 2.47, showing significant improvement in the patient’s symptoms.

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a systemic inflammatory form of arthritis that primarily affects the axial skeleton and sacroiliac joints, leading to fusion of the spine. It can also affect peripheral joints and entheses, as well as having extra-musculoskeletal manifestations, which can lead to pulmonary, cardiac, ophthalmic, and neurological complications. AxSpA affects between 0.1/0.2 per cent of people in Ireland, with a global prevalence estimated at 0.32-to-0.7 per cent. It can lead to a chronic and disabling condition, which can have major impacts on physical and mental health, as well as work productivity and socio-economic costs.

Pathogenesis

AxSpA is the prototype form of a spectrum of conditions known as spondyloarthritis (SpA). In more recent years, axSpA encompasses a broader phenotype, which includes both radiographic axSpA, also known as ankylosing spondylitis (AS), and non-radiographic axSpA (nr-axSpA), which may represent early or milder forms of disease.

AxSpA is an immune-mediated condition with characteristic clinical features including sacroiliitis and spondylitis, enthesitis, peripheral arthritis, and extra-musculoskeletal manifestations (EMMs), which include uveitis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and psoriasis.

The disease process is characterised by activation of an inflammatory process leading to cartilage and bone loss, followed by remodelling and new bone formation, resulting in bone fusion and sclerosis of the sacroiliac joints (SIJs) and axial skeleton.

Although the pathogenesis of axSpA is still not completely understood, it appears to be multifactorial, with genetics shown to play a significant role as well as several proposed exogenous factors. HLA-B27 allele inheritance has a strong association to axSpA, and although variable among ethnicities, HLA-B27 has a worldwide prevalence of about 8 per cent in the general population, and is positive in 74-to-89 per cent of patients with axSpA. Other genetic factors thought to be involved are those influencing antigen presentation and the interleukin (IL)-23/17A pathway.

Figure 1: SIJ x-ray in 2007 showing SIJ widening and early changes of sacroiliitis | Figure 2: SIJ x-ray in 2015 showing bilateral sclerosis and erosions | Figure 3: SIJ x-ray in 2023 showing bilateral ankylosis

Clinical manifestations

Onset of symptoms typically occurs between 20 and 30 years of age. Patients tend to present with inflammatory back pain (IBP) that starts before 45 years of age. Cardinal features of IBP include insidious onset, symptom duration of over three months, improvement with exercise and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and early morning wakening secondary to pain.

Psoriasis is said to affect approximately 10 per cent of patients with axSpA, however, there is ongoing debate regarding patients with psoriatic disease and axial involvement, also known as axial psoriatic arthritis (axPsA), and whether this is a separate disease entity. Although treatment options currently remain the same, patients can present differently in axPsA than in classical axSpA. Improved awareness of these differences in presentation is needed to improve recognition of axial involvement and prevent disability.

Differences include the age of onset, which can occur after 45 years of age, a lower rate of HLA-B27 positivity, and typical IBP has been reported in approximately only 50 per cent of axPsA patients. Radiographic differences include a lower grade and more asymmetrical sacroiliitis on MRI findings in axPsA. It is also noted that one-third of axPsA patients have spondylitis without sacroiliitis, unlike axSpA, where it is thought sacroiliitis occurs before or concurrently with spondylitis.

Uveitis is typically characterised by acute, painful, unilateral inflammation in the anterior chamber of the eye, which can present with acute pain, photosensitivity, and blurred vision. It is the most common EMM in axSpA, with reports showing up to 30 per cent of patients affected. It has also been shown to be HLA-B27-associated and has been linked to worse physical function and disease severity in axSpA patients.

The pathogenesis that links IBD and axSpA is still poorly understood. IBD is said to be clinically evident in 4-to-14 per cent of axSpA patients, with silent gut inflammation occurring in up to 60 per cent. AxSpa is more commonly observed in Crohn’s disease than in ulcerative colitis, with up to 20 per cent of patients with silent inflammation going on to develop Crohn’s disease within five years. IBD is seen in axSpA patients more than the general population and can be associated with disease severity.

Peripheral symptoms encompass enthesitis, dactylitis, and peripheral inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis and enthesitis are the most common, while predominantly affecting the lower limb. Enthesitis refers to inflammation of the entheses, where tendons, joint capsule fibres, or ligaments insert into the bone.

Enthesitis has a prevalence of approximately 35-to-60 per cent in axSpA, and can be associated with higher disease activity, as well as a significantly negative impact on the patient’s quality-of-life. The prevalence of peripheral arthritis varies according to disease duration, with a prevalence of 15-to-21.3 per cent in newly-diagnosed patients at baseline, and 37.4-to-50 per cent in patients with a longer disease history. This shows an increased prevalence with longer disease duration.

Diagnosis

AxSpA diagnosis remains challenging; with an average delay in diagnosis ranging from seven-to-10 years, and previous studies suggest patients with a delayed diagnosis may have a more aggressive disease course, with increased work disability reports and reduced quality-of-life and functional capacity.

Despite improvements in recent years, delays in diagnosis are notably multifaceted, with a low awareness among physicians still playing a pivotal role among other factors. Ultimately, the diagnosis of axSpA will be based on a combination of symptoms assessed through clinical history, physical examination, laboratory investigations, and imaging.

The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) has developed classification criteria for axSpA. These are based on the presence of sacroiliitis on imaging or HLA-B27 positivity in the presence of other SpA features. SpA features included in the classification criteria are: Arthritis, dactylitis, enthesitis (heel), a good response to NSAIDs, uveitis, Crohn’s disease/colitis, and a family history of axSpA.

Nr-axSpA is used to describe axSpA without definitive radiographic sacroiliitis, but that describes inflammation of the SIJs on MRI. AS, also referred to as radiographic-axSpA, describes radiographic sacroiliitis, which is based on the 1984 modified New York criteria, showing bilateral, grade 2-to-4 sacroiliitis or unilateral grade 3-to-4 sacroiliitis.

It is worth noting that typical IBP symptoms, fatigue, and presence of peripheral symptoms or EMMs can be present for several years before radiographic changes are detected. The ASAS classification criteria for axSpA has shown an 82.9 per cent sensitivity and an 84.4 per cent specificity.

Treatment

The management of patients with axSpA includes non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions and requires a multidisciplinary approach. In 2022, the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) and ASAS published recommendations for the management of axSpA, stating that treatment should focus on control of symptoms and inflammation, maximising health-related quality-of-life, and preventing progressive structural damage. With advancements in treatment in recent years, the recommendations focus on a more tailored approach to treatment based on clinical manifestations and patient characteristics, including comorbidities and psychosocial factors.

Initial recommendations focus on treatment targets and monitoring disease. This should include patient-reported outcomes (PROs), clinical examination, laboratory investigation, and imaging as clinically appropriate. The frequency of monitoring should be based on disease activity and severity, clinical manifestations, and treatment course.

As with other inflammatory diseases, disease activity scores can be used to monitor and document disease activity. The Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), calculated using C-reactive protein (CRP), is now being recommended when monitoring patients with axSpA. However, the more historically used Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) can also be used. Both scores include the perspective of the patient, but the main difference between the two is that ASDAS incorporates CRP, for an objective measurement of inflammation.

Four disease activity states can be shown using ASDAS including: Inactive disease, moderate, high, and very high disease activity. The three cut-offs to separate these activity states are: 1.3, 2.1, and 3.47. Further monitoring in clinical practice includes questionnaires collecting PROs for levels of pain, fatigue, morning stiffness, and physical function, as well as assessing swollen joint counts, EMMs, and spinal mobility.

Non-pharmacological management includes patient education, physiotherapy, and lifestyle modifications, including smoking cessation and regular exercise, and this should be discussed at the time of diagnosis.

NSAIDs are the first-choice pharmacological treatment for axSpA and are recommended to be taken as-needed for patients suffering from pain and stiffness. Continuous use is preferred for patients who respond well to NSAIDs, taking risk versus benefits into account. Patients should be trialled on at least two different NSAIDs at the maximum dose, used over a total period of four weeks to assess effect.

Patients with purely axial disease should not receive long-term treatment with systemic glucocorticoids due to lack of efficacy; however, recent studies suggest that short-term high-dose glucocorticoids could have a modest effect on signs and symptoms in patients with purely axial disease.

Conventional synthetic DMARDS (csDMARDS), such as methotrexate, leflunomide, or sulfasalazine, have a minimal role in patients with purely axial disease, however, sulfasalazine can be used for peripheral arthritis in patients with axial disease. In patients having failed NSAIDs, further treatment options include biological DMARDs (bDMARDs) or targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs) in the form of Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi).

Patients who have an ASDAS of ≥2.1 and who have failed ≥2 NSAIDs, and have an elevated CRP or noted inflammatory changes of SIJs on MRI or radiographic sacroiliitis on x-ray, should be commenced on tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) or IL-17 inhibitors. TNFi and Il-17i are preferred as first-line over JAKi due to larger evidence of efficacy, experience of use in patients with multiple comorbidities, and an increased knowledge about drug safety.

In the case of a first bDMARD or tsDMARD failure, switching to another TNFi or IL-17i or a JAKi should be considered. It is also important to consider EMMs or peripheral symptoms when choosing a treatment. In patients with a history of recurrent uveitis or active IBD, preference should be given to a monoclonal antibody against TNF, where an IL-17i may be preferred in patients with significant psoriasis.

In summary

Even with recent advances in identifying axSpA, the diagnosis remains challenging, with patients experiencing significant delays until a diagnosis is reached. The case study in this article highlights progression over time leading to disability, unemployment, and reduced quality-of-life in patients who are misdiagnosed or have a delayed diagnosis. As therapies are now available to control both symptoms and prevent radiographic progression, it is imperative patients are assessed and referred to rheumatology services promptly.

Lower back pain in adults is a common presentation in daily practice. Patients who suffer from chronic back pain often seek care from GPs, spinal surgeons, pain specialists, or physiotherapists. Education of the new axSpA spectrum and cardinal features of IBP are needed to prevent patients being prescribed heavy analgesia or undergoing unnecessary procedures.

As with this case, patients may also present with EMMs to gastroenterologists, dermatologists or ophthalmologists, highlighting the importance of awareness of SpA features across multiple specialties.

Education relating to axSpA should be enhanced among healthcare professionals to avoid diagnostic delays and prevent radiographic progression, which may lead to loss of functionality, reduced quality-of-life, and possible disability.

References available on request

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.