Reference: November 2024 | Issue 11 | Vol 10 | Page 25

Diabetes is a serious chronic disease which carries devastating complications such as renal disease, blindness, peripheral neuropathy, diabetic foot disease (DFD), and lower limb amputations. The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing estimates that 10 per cent of adults aged 50 years and older have type 2 diabetes (T2D) and 16 per cent of those aged 80 years and older.1 This rising figure is of particular concern, as the report further suggests that one-in-10 people remain undiagnosed and untreated for their diabetes, resulting in increased risks for future complications such as DFD.

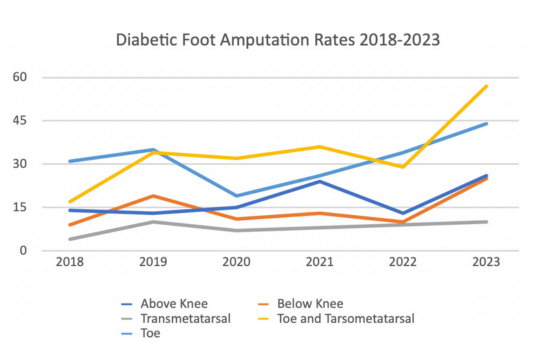

DFD accounts for a growing percentage of hospital admissions due to the development of chronic

foot ulcerations. This has been reflected in an acute tertiary level hospital in Ireland with persistently rising rates of major and minor lower limb amputation (Figure 1).

These figures have a significant influence over the healthcare budget in Ireland, directly affecting the provision of care for all patients. A registry-based study estimated the approximate costs of a minor diabetic foot amputation to be €23,940, and €42,814 for a major amputation.2 These figures do not account for the full burden of disease and it is well reported in the literature that the five-year mortality rate post lower limb amputation is over 50 per cent.3

Current guidelines within the HSE stress the importance of preventative care to identify, educate, and manage DFD. A significant portion of amputations are classified as preventable with timely accessibility to care. However, barriers exist in the provision of this timely care.

BlueDop audit

Inadequate resources, funding, and staffing levels are all contributing factors that reduce timely access to care. An Irish tertiary level hospital was able to identify in an audit that patients were waiting 10 weeks on average for non-invasive vascular assessments, such as ankle brachial pressure indices (ABPIs) and toe brachial pressure indices (TBPIs).

These tests are widely used to diagnose peripheral arterial disease, which is a major risk factor for DFD and helps steer clinical decision making. Delays in interventions and assessments are associated with increased amputation rates and poor outcomes.4 The BlueDop is a non-invasive bedside measurement of peripheral arterial disease and can be used as an alternative to the gold standard ABPIs and and TBPIs.

The BlueDop device was invented by Vascular Scientist David H King in 2010, and measures the arterial blood pressure in the posterior tibial or dorsalis pedis artery through an algorithm. The device then extrapolates information in respect to the velocity of the blood flow and waveform. Additional data such as the brachial arm pressure is inputted, providing the user with a cuff-free ABPI. The result is communicated wirelessly to a tablet monitor.

The BlueDop has several benefits. It can identify peripheral arterial disease, the test can be performed at the bedside by a podiatrist or a nurse, it requires minimal training, and is easy to execute. BlueDop does not need to be performed in a vascular lab by a vascular technician; and so, delays in diagnosing peripheral arterial disease are reduced.

FIGURE 1: Diabetic foot amputation rates at an Irish tertiary level hospital

Aims and objectives

The primary objective of the audit was to compare the BlueDop with the hospital vascular laboratory; assessing its accuracy and reliability. The overarching aim was to ascertain the level of value the BlueDop would offer in a clinical setting.

Methodology

The audit was retrospective in nature and resulted in a sample size of 23 patients who met the essential criteria – a history of diabetes and an active foot ulceration. Patient records and results were evaluated across a number of platforms including CELLMA, NIMIS, McKesson Radiology Manager, and HIPE data. The data was collected, anonymised, and entered into a working excel document in line with GDPR requirements.

Findings

General demographics

All of the subjects except for one were male, 20 of the 23 patients had T2D, and the remainder had T1D. Average age of the sample was 67 years. The majority of cases had a history of hypertension, high cholesterol, and many had received some level of vascular intervention (39 per cent). A total of 17 per cent were smokers and 4 per cent had end stage renal failure.

Accessibility to care

Accessibility to care was determined by the wait time for either a podiatry appointment or for ABPIs in the vascular laboratory. Wait time to see the podiatrist and have the BlueDop performed was 11 working days. The Bluedop assessment took an average of 13 minutes to perform.

The average wait time for the vascular laboratory assessment to have ABPIs and TBPIs was 10 weeks in nine cases, the other 14 cases were still awaiting a vascular laboratory appointment by the time the audit had finished. There were a further two cases of booked vascular studies that were cancelled with no rescheduled date.

Comparability to the traditional ABPI

Non-compressible vessels: Peripheral arterial disease and vessel calcification is a common occurrence in diabetic patients. A significant portion of the cases (five) indicated non compressible vessels in excess of 250mmHg. However, the Bluedop was able to produce an ABPI reading and mmHg values for all of these cases, as the technology is not impacted by vessel calcification.

Variation in assessment locations: The location of the peripheral pulse was not consistent between the two devices. The Bluedop only assessed the posterior tibial pulse location, whereas dorsalis pedis was often assessed in the vascular reports reviewed. This variation in locations makes it difficult to draw consistent trends and comparisons.

Audit design: The audit design was a major limitation in this study, as the auditing team was not comparing data from the same point in time, therefore, making it impossible to draw an accurate comparison. Around 65 per cent of ABPIs reports reviewed from the vascular lab were more than 12 months old. This further demonstrates a significant level of strain on the service. Further refinement of the audit design would allow for a direct comparison.

Discussion

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines outline that under the suspicion for peripheral arterial disease, a cardiovascular, ABPI, and doppler assessment must be performed.5 These assessment tools are operator dependent and can produce skewed readings due to arterial calcification, often seen in diabetes and ageing demographics. ABPIs and TBPIs can be difficult to do in patients with active foot ulceration as the site of the ulcer can interfere with the application of the test.

Accessibility to care is outlined in the HSE Diabetic Foot Model of Care6 as a key requirement for a multidisciplinary foot unit. To facilitate this, the correct provision of resources and adequate staffing levels are required. The results identify that there are significant wait times for bedside vascular studies in laboratory setting in the tertiary hospital. This patient demographic has active DFD and delayed access to care will impact outcomes.

This audit was undertaken during the time of the HSE recruitment embargo, likely further impacting staffing levels and the provision of care to some degree. The audit did not assess if there were any amputations as a result of the delayed access to care. However, all ulcerations remain active to date.

The BlueDop is a portable device that can be used in an outpatient setting or in the community, allowing for an immediate bedside vascular assessment, with an average assessment time of 13 minutes. It is a user-friendly device which can be operated by a multitude of healthcare professionals. Increasing vascular screening services at community level may reduce the strain on tertiary level services as inappropriate referrals can be effectively triaged.

The premise of the audit was not to determine whether the BlueDop is as accurate as the ABPI machine or could replace the ABPI machine as a diagnostic test. The rationale was that a small cohort of patients were and are still waiting to have their up-to-date ABPIs performed in the vascular laboratory.

Due to these limitations, previous ABPI results done at different time points were used as a comparison for the audit, however the location of the peripheral pulse differed between the BluDop device and the ABPI reports reviewed. Therefore, more patients and a standardisation of the BluDop and ABPI examination is required before we could say that the BluDop machine could take the place of the ABPI in the measurement of peripheral arterial disease in people with diabetes.

Limitations

Audit design is a major limitation as it was reliant on previously performed vascular studies. Conducting a study in lab conditions at the same point in time would provide a clearer picture. The sample size was relatively small, limiting its applicability.

Conclusion

Due to study design limitations, an accurate conclusion cannot be drawn in respect to comparing ABPIs at a tertiary level hospital vascular laboratory to the BlueDop. The study demonstrates significant strains on the healthcare system, with wait times impacting patient outcomes.

The BlueDop device is an innovative tool that could be used in a multitude of settings to help triage and direct care patient care. However, further research needs to be performed to conclude if this tool can replace traditional ABPI methods.

References

- Leahy S, O’ Halloran AM, O’Leary N, et al. Prevalence and correlates of diagnosed and undiagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus and pre-diabetes in older adults: Findings from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;110(3):241-249.

- Mealy A, Tierney S, Sorensen J. Lower extremity amputations in Ireland: A registry-based study. Ir J Med Sci. 2022;191(2):839-844.

- McPherson M, Carroll M, Stewart S. Patient-perceived and practitioner-perceived barriers to accessing foot care services for people with diabetes mellitus: A systematic literature review. J Foot Ankle Res. 2022;15(1):92.

- Nickinson ATO, Bridgwood B, Houghton JSM, et al. A systematic review investigating the identification, causes, and outcomes of delays in the management of chronic limb-threatening ischaemia and diabetic foot ulceration. J Vasc Surg. 2020;71(2):669-681.e2.

- Kordzadeh A, Hoff M, Tokidis E, King DH, Browne T, Prionidis I. Novel assessment (BlueDop) device for detection of lower limb arterial disease: A prospective Comparative Study. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37(3):763-768.

- Health Service Executive. Diabetic foot model of care. Dublin: HSE; 2022. Available at: www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/cspd/ncps/diabetes/moc/diabetic-foot-model-of-care-2021.pdf.