Reference: March 2025 | Issue 3 | Vol 11 | Page 46

Since 1950, advancements in medicine, public health, and living conditions have significantly extended human life expectancy, adding several decades to lifespan across many countries. By 2030, an estimated 57 per cent of women will exceed the 90-year life expectancy threshold – an achievement once thought impossible. Nearly half of all women will spend a substantial portion of their lives in the postmenopausal phase. A deeper understanding of menopause and its widespread impact on health and ageing has never been more essential.

Defining menopause

Menopause is defined as the final menstrual period, confirmed when a woman has gone 12 consecutive months without a period and no other medical cause is present. However, accurately determining the onset of menopause can be challenging in modern times, especially for women using hormonal contraceptives or intrauterine devices, which may suppress or alter menstrual patterns.

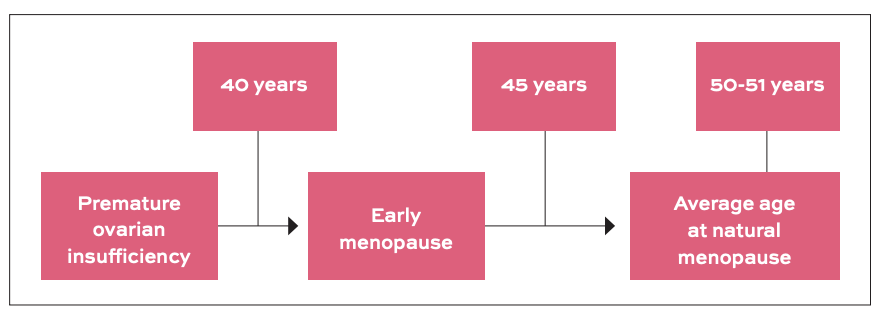

To provide further clarity, the European Menopause and Andropause Society (EMAS) classifies menopause based on the age of onset (Figure 1). Premature ovarian insufficiency is diagnosed when menstruation stops before the age of 40, while early menopause occurs between 40 and 45 years. The average age of natural menopause is approximately 50.5 years, after which a woman enters the post-menopausal phase.

The physiology of oestrogen

Oestrogen is a key hormone that regulates many functions in a woman’s body, including reproductive health, bone density, and cardiovascular protection. As menopause approaches, oestrogen levels begin to decline, eventually reaching very low levels after the final menstrual period. This hormonal shift is responsible for many of the symptoms associated with menopause, including hot flashes, mood changes, and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Among these, vasomotor symptoms, which primarily include hot flashes and night sweating, can significantly affect daily life, leading to fatigue, insomnia, and irritability. These symptoms typically begin during perimenopause and affect approximately 84 per cent of women worldwide.

While they generally persist for four to five years after menopause, up to 25 per cent of women may continue to experience them for 10 years or longer. Additionally, they are often accompanied by feelings of anxiety, depression, mood swings, and irritability. Chronically disturbed sleep, linked to vasomotor symptoms, can further exacerbate irritability, fatigue, concentration problems, as well as muscle and joint pain.

Cardiovascular health in women: The shifting risk

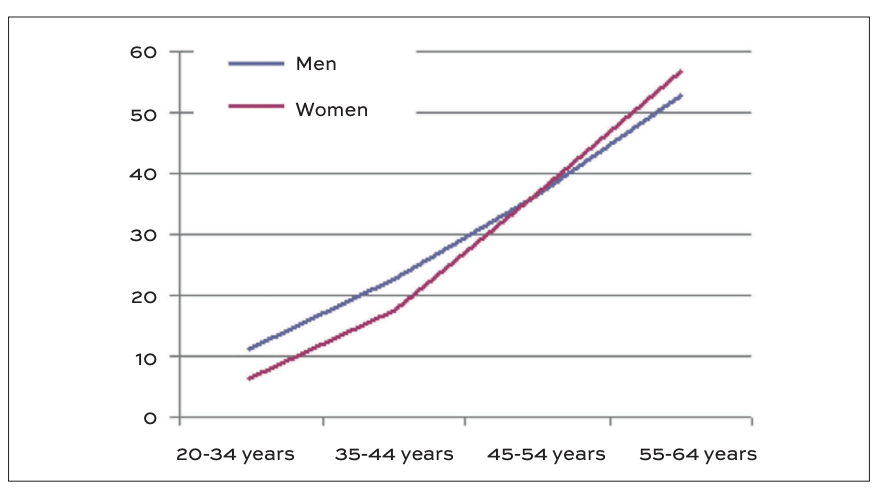

Pre-menopausal women have a significantly lower incidence of cardiovascular disease compared to men of the same age. However, this protective advantage diminishes after menopause, with older women experiencing a higher cardiovascular risk (Figure 2). While ageing and hormonal changes both contribute, substantial evidence indicates that reduced oestrogen levels are a major factor in this increased risk.

Studies such as the Nurse’s Health Study and the WISE Study have shown that early menopause, whether due to ovarian dysfunction or bilateral oophorectomy, is associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease compared to women with normal oestrogen levels. These findings have cemented oestrogen’s role as a key cardioprotective hormone.

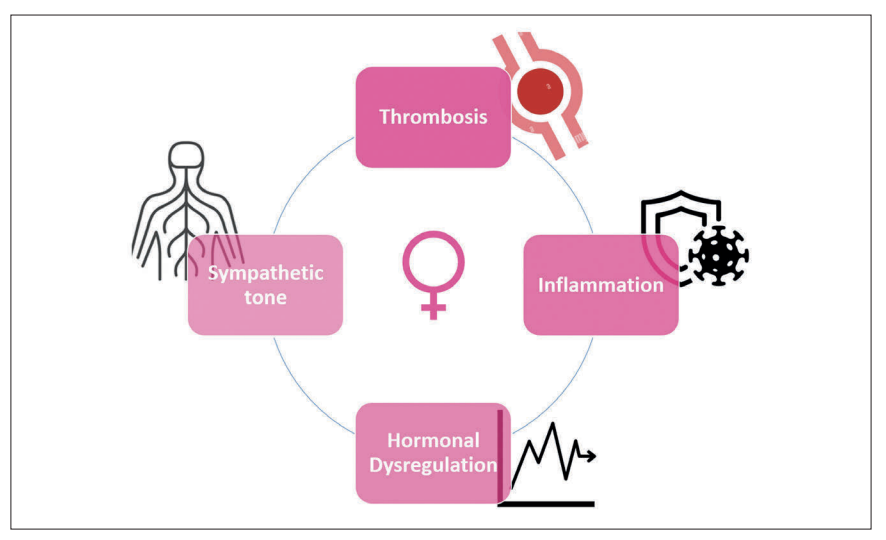

The heightened cardiovascular risk observed in women during the perimenopausal phase has been partially attributed to several factors identified in various studies, including elevated inflammatory markers, increased sympathetic activity, and a higher propensity for thrombosis (Figure 3).

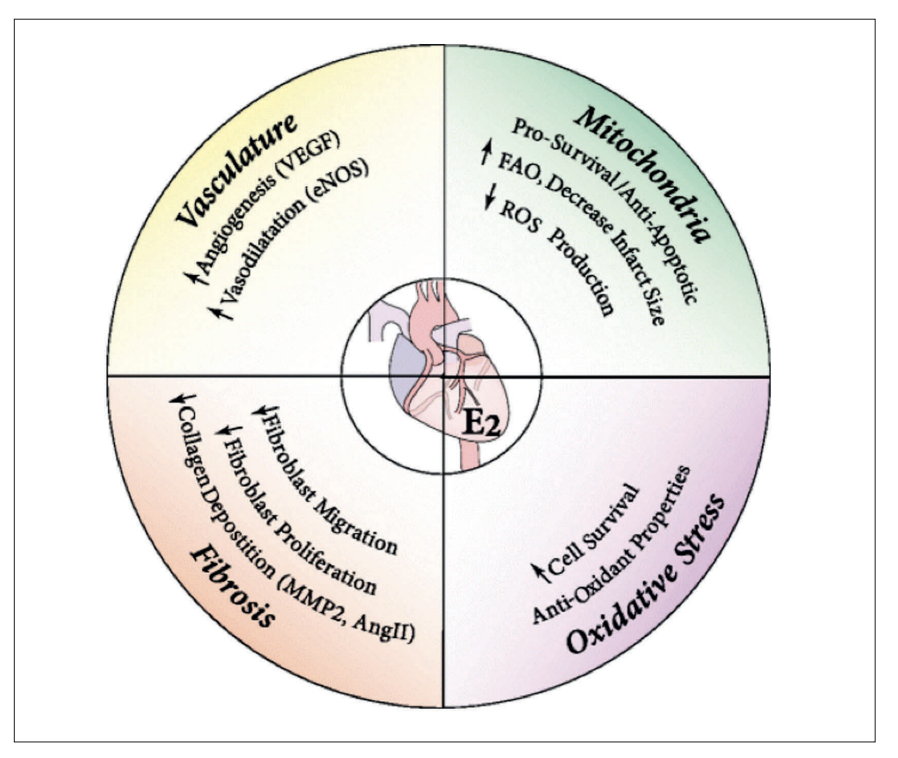

Compounding these harmful mechanisms is the depletion of oestrogen, which removes its multifaceted cardioprotective effects as illustrated in Figure 4. Oestrogen supports vascular health by enhancing angiogenesis (formation of new blood vessels) and promoting vasodilation, both of which maintain optimal blood flow and reduce arterial stiffness. Its mitochondrial protective role includes reducing oxidative stress and promoting cell survival, thereby mitigating damage to cardiac cells.

Oestrogen also prevents excessive fibrosis by reducing collagen deposition, which helps maintain heart tissue elasticity and function. Finally, its antioxidant properties counteract oxidative damage that can lead to chronic inflammation and atherosclerosis. The loss of these protective effects in post-menopausal women leaves them more vulnerable to endothelial dysfunction, arterial plaque formation, and other cardiovascular risks.

The rise and fall of hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

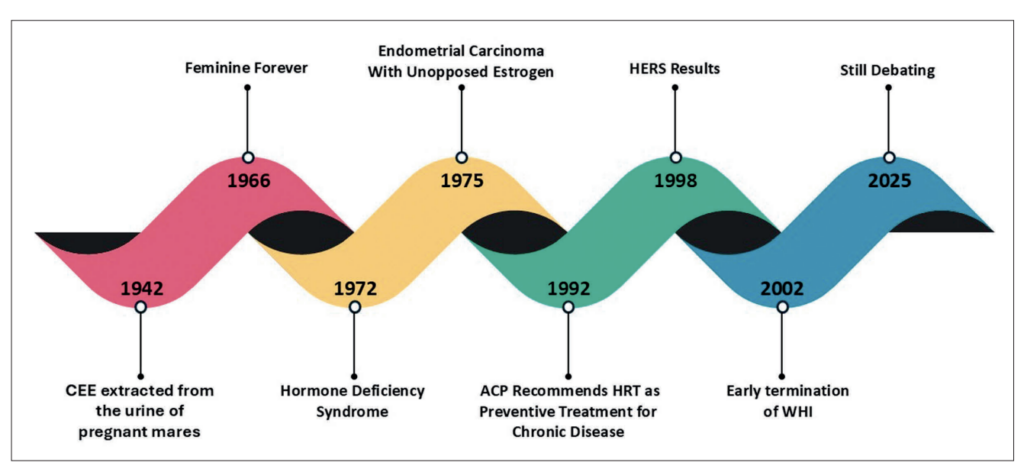

The recognition of oestrogen’s critical role in women’s health, particularly its cardioprotective and symptom-alleviating effects, led to the development of HRT as a therapeutic approach. Since its inception, HRT has undergone significant evolution – from being hailed as a groundbreaking solution to later becoming a topic of controversy and intense research (Figure 5). Understanding the history of HRT provides valuable context for its current role in managing menopause-related symptoms and health risks.

In 1942, premarin (conjugated equine oestrogens) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as one of the first widely used HRTs. Extracted from the urine of pregnant mares, its exact composition – a mix of various oestrogens – was not fully understood at the time due to limited analytical techniques.

Its approval was based on observational evidence and clinical experience, as it predated the rigorous requirements for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) established by the Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments of 1962. As premarin gained popularity, the cultural narrative around menopause began to shift, fuelled in part by the claims of influential figures like Dr Robert A Wilson.

In 1966, Dr Wilson’s book Feminine Forever became a bestseller, promoting the idea that oestrogen therapy was essential for menopausal women to retain their femininity, youth, and vitality. He framed menopause as a ‘deficiency disease’, describing it in highly negative terms, and warning that untreated women would become ‘dull’, ‘wrinkled’, and ‘sexless’. Wilson even suggested that oestrogen could prevent ageing, making women ‘forever feminine’.

His claims fuelled the widespread adoption of HRT, portraying it as not only safe, but necessary for all menopausal women due to its cardioprotective properties. However, it was later revealed that Wilson received financial support from Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, the manufacturer of premarin, raising ethical concerns about the objectivity of his advocacy.

Building on Wilson’s influence, by the 1970s, the medical community increasingly framed menopause as a hormone deficiency syndrome, akin to other endocrine disorders. This perspective further reinforced the widespread use of HRT – not only to alleviate symptoms like hot flashes and vaginal dryness, but also as a supposed remedy for ageing related concerns. However, this medicalised view of menopause has since been criticised for pathologising a natural life stage, while downplaying the potential risks of HRT.

In 1975, a pivotal revelation shocked the medical community, exposing the risks of HRT, which had been widely prescribed for decades without rigorous scientific scrutiny. For years HRT was promoted largely based on propaganda, with claims about its benefits often fuelled by cultural narratives and commercial interests rather than robust evidence.

Research by Smith et al finally demonstrated a significant link between unopposed oestrogen therapy (oestrogen without progesterone) and a 4.5-fold increased risk of endometrial cancer. This landmark finding marked a critical turning point, highlighting the controversies surrounding the overprescription of HRT.

Upon these findings, the Nurses’ Health Study, one of the largest studies of its kind (involving 121,700 registered nurses), was initiated in the US. Initial observational data from the study suggested that HRT might lower the risk of heart disease. However, these findings were far from conclusive as they were not derived from RCTs, which are the gold standard for establishing causation.

Despite the lack of strong evidence from RCTs, limited safety data, and ongoing controversies surrounding HRT, the American College of Physicians recommended HRT in 1992 for the prevention of chronic diseases including coronary artery disease. This decision continues to be questioned, as it highlights the medical community’s reliance on incomplete data in the absence of rigorous studies.

Another blow to HRT advocates came in 1998 with the publication of the Heart and Oestrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS) – the first ever randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to rigorously evaluate HRT in 2,763 women with established coronary artery disease.

This landmark study disproved the long-standing assumption that HRT was cardioprotective and, instead, exposed its potential risks. In the first year of HRT use, there was a 52 per cent increased risk of coronary artery disease events in the HRT group compared to placebo (HR 1.52, 95% CI: 1.01-2.29). Furthermore, long-term use of HRT was linked to a two-fold increased risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, raising urgent safety concerns.

Although HRT advocates argued that the HERS findings applied only to women with pre-existing coronary artery disease, this defence was shattered in 2002 when the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) delivered the final and most damning evidence against HRT.

This large, landmark RCT was designed to comprehensively assess the risks and benefits of HRT in 16,608 healthy postmenopausal women, unlike previous observational studies. However, the trial was abruptly terminated earlier than planned due to alarming safety concerns.

The WHI findings confirmed and expanded upon HERS, revealing that HRT use led to a 29 per cent increased risk of myocardial infarction, a 41 per cent increased risk of stroke, and more than double the risk of pulmonary embolism.

Furthermore, it demonstrated a 26 per cent increased risk of breast cancer, with the likelihood rising further with prolonged use. The study also documented significant increases in cardiovascular and cancer-related deaths, ultimately forcing investigators to halt the trial prematurely.

These findings ignited a never-ending debate regarding the safety of HRT, turning it from a presumed fountain of youth into a therapy requiring extreme caution. Once hailed as an essential treatment for all menopausal women, HRT was now viewed through a far more critical lens, as the risks appeared to outweigh the benefits.

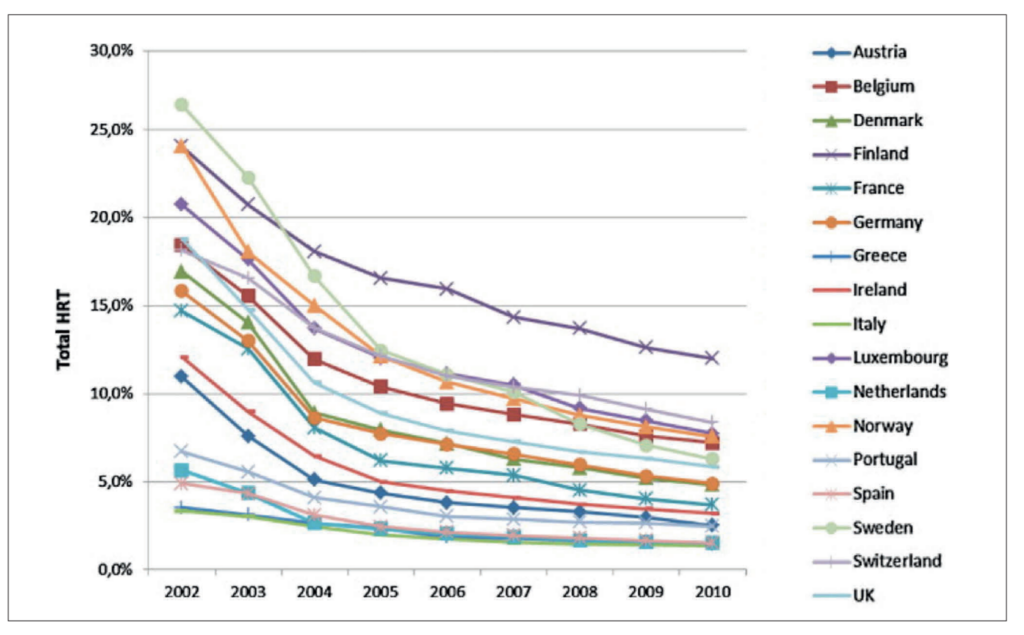

The WHI findings led to a sharp decline in prescriptions, shifting medical perspectives and raising ethical questions about how menopause had been framed as a condition needing medical intervention (Figure 6).

Revisiting HRT: Controversies and critiques

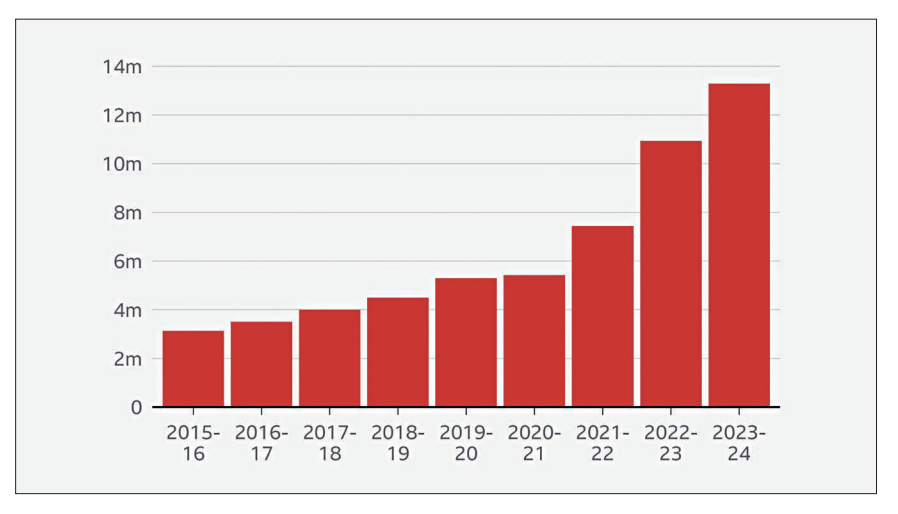

Despite the initial decline in HRT prescriptions following the WHI study, recent data from the UK and the US suggest a resurgence in HRT use, often without robust scientific evidence to support its safety and efficacy (Figure 7). This resurgence is fuelled by critics who argue that the WHI study was flawed and insufficient to justify the drastic reduction in HRT usage.

| HEALTH EVENT | RR VS PLACEBO GROUP AT 5.2 YEARS (95% CI) | INCREASED AR PER 10,000 WOMEN/YEAR | AR REDUCTION PER 10,000 WOMEN/YEAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| MI | 1.29 (1.02-1.63) | 7 | ND |

| Stroke | 1.41 (1.07-1.85) | 8 | ND |

| Breast cancer | 1.26 (1.00-1.59) | 8 | ND |

| Thromboembolic events | 2.11 (1.58-2.82) | 18 | ND |

| Colorectal cancer | 0.63 (0.43-0.92) | ND | 6 |

| Hip fractures | 0.66 (0.45-0.98) | ND | 5 |

| RR: Relative risk; AR: Absolute risk; ND: No data; MI: Myocardial infarction | |||

TABLE 1: Data from the WHI

One of the primary critiques centres on the fact that the WHI study employed a single type of HRT – CEE 0.625mg/day combined with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) 2.5mg/day – which contains higher oestrogen levels than many modern formulations. While this argument seems legitimate, it overlooks that WHI utilised the most prescribed HRT dosage and type of the 1990s and early 2000s.

Another major critique focuses on the claim that modern HRT formulations, such as transdermal oestrogen and bioidentical hormone therapy, differ significantly from the oral CEE and MPA used in WHI. Proponents argue that transdermal HRT bypasses hepatic first-pass metabolism, potentially reducing thromboembolic risks, while bioidentical formulations may provide a more favourable safety profile compared to synthetic progestins.

While observational studies have consistently reported lower rates of venous thromboembolism with transdermal compared to oral HRT, no RCTs have directly compared venous thromboembolism risk across oral, transdermal, and placebo therapy.

This reliance on observational data is concerning, as past observational studies also suggested oral HRT was cardioprotective – until large-scale RCTs like HERS and WHI decisively disproved that assumption. The same overreliance on non-randomised data risks misleading interpretations about transdermal HRT’s safety, emphasising the need for high-quality trials before making definitive conclusions.

Similarly, no studies have directly compared bioidentical hormone therapy with standard synthetic hormone therapy regarding cardiovascular outcomes, leaving claims of superior safety unproven. While some FDA-approved bioidentical HRT options exist, most compounded bioidentical formulations are not FDA-regulated – raising concerns about dosing inconsistencies, absorption, and contamination.

As a result, guidelines advise using FDA-approved formulations whenever possible due to their standardised production and safety profile. Until robust clinical trials evaluate long-term cardiovascular risks, any purported advantage of bioidentical hormone therapy remains speculative.

In summary, while transdermal and bioidentical formulations are increasingly popular, current consensus guidelines do not consider them inherently safer than standard HRT due to insufficient randomised data on long-term cardiovascular and cancer outcomes.

Nevertheless, some clinicians remain optimistic about transdermal HRT potentially lowering thromboembolic risk; however, its overall cardiovascular impact remains unclear, and similar concerns apply to bioidentical HRT, which also lacks rigorous safety monitoring.

These uncertainties highlight the broader issue of how risk assessment in WHI has been debated, with some arguing that the study overemphasised relative risk rather than absolute risk, potentially exaggerating the perceived dangers of HRT. However, a sub-analysis addressing this critique found that even the absolute risks were significantly unfavourable for HRT, reinforcing the study’s conclusions (Table 1).

Health event

Another point of contention has been the high dropout rate in the WHI trial, with 42 per cent of women in the HRT group discontinuing their medication before the study’s completion. Critics argue that this could have diluted the observed risks. In response, WHI investigators conducted sensitivity analyses to adjust for adherence, which revealed even higher hazard ratios for coronary artery disease, breast cancer, stroke, and venous thromboembolism. These findings suggest that the risks associated with HRT were, in fact, underestimated rather than overstated.

The timing hypothesis: HRT’s potential ‘window of opportunity’

Faced with mounting evidence against the safety of HRT, advocates introduced the timing hypothesis, hoping to salvage its potential cardiovascular benefits. This hypothesis posits that the cardiovascular and overall health benefits of HRT may depend on the timing of its initiation, particularly in relation to a woman’s age and the onset of menopause.

Supporters of this hypothesis argue that younger women in the WHI study – those between the ages of 50 and 59 – seemed to fare better. In fact, within this subgroup, the mortality rate was lower in the HRT group compared to the placebo group, with the placebo arm showing higher mortality rates.

While this observation has been cited as evidence supporting the timing hypothesis – suggesting that HRT may have cardiovascular benefits if initiated early in menopause – it is essential to approach such claims with caution. The WHI study, while landmark in its scope, was not designed or adequately powered to rigorously evaluate the timing hypothesis or to draw definitive conclusions based on age or time since menopause onset. Its primary objective was to assess the overall risks and benefits of HRT in a diverse population of post-menopausal women, without delving deeply into nuanced factors like timing or pre-existing cardiovascular health.

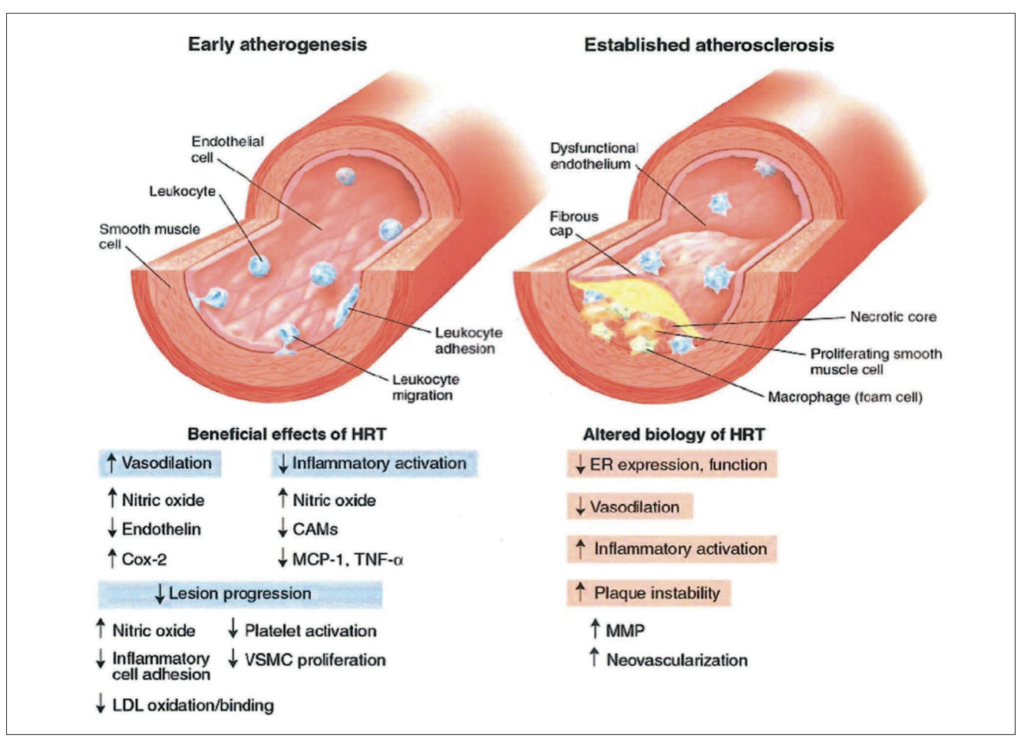

Proponents of the timing hypothesis argue that initiating HRT in the early stages of menopause, before atherogenesis (the development of arterial plaque) has begun, may offer benefits. They posit that early intervention could leverage oestrogen’s effects on vasodilation, reduced inflammation, and slower progression of atherosclerosis (Figure 8).

However, these same proponents also acknowledge that when plaques are already present, HRT may exacerbate risks, potentially promoting plaque instability or thrombosis. While intriguing, this dual effect – protective in early phases and harmful in later stages – raises questions about the mechanistic consistency of HRT’s actions.

In early stages, HRT demonstrates beneficial effects, including enhanced vasodilation, reduced inflammatory activation, decreased lesion progression, and inhibition of low density lipoprotein oxidation and inflammatory cell adhesion.

Conversely, in established atherosclerosis, HRT may contribute to adverse outcomes such as reduced oestrogen receptor function, increased inflammatory activation, impaired vasodilation, plaque instability, and neovascularisation.

If the timing hypothesis is to be validated, it necessitates robust evidence from well-designed RCTs specifically tailored to evaluate the interplay between timing, cardiovascular health, and HRT. Until such data is available, these claims remain speculative.

In 2014, one such attempt to investigate the timing hypothesis was the Kronos Early Oestrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS). This trial included 727 women aged 42 to 59 who were within three years of menopause onset (recently menopausal).

Participants were generally healthy and had no significant cardiovascular disease or other major health issues. They were randomised to receive either oral oestrogen, transdermal oestrogen, or placebo. After 48 months, the study evaluated carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT), a well-established marker of cardiovascular risk.

Despite initial hopes, KEEPS found no significant differences in CIMT between the groups, regardless of the form of oestrogen administered. These results challenged the notion that early initiation of HRT provides measurable cardiovascular benefits, casting further doubt on the validity of the timing hypothesis.

Two years later, in 2016, the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Oestradiol Study (ELITE) sought to further explore the timing hypothesis. This trial stratified 643 healthy participants into two groups based on their time since menopause onset: Women who were less than six years post-menopause and those who were over 10 years post-menopause.

ELITE reported a statistically significant reduction in CIMT progression in the group receiving HRT within six years of menopause onset compared to placebo (P = 0.008). However, the older cohort – those who were more than 10 years post-menopause – showed no significant difference in CIMT progression between the HRT and placebo groups. While these findings initially seemed to support the timing hypothesis, further scrutiny revealed the clinical insignificance of the CIMT reduction.

Dr Howard Hodis, the lead investigator of ELITE, had previously stated in 1998 that a reduction in CIMT progression of less than 0.011mm/year was unlikely to have a meaningful impact on cardiovascular outcomes. In ELITE, the observed reduction in CIMT progression was 0.0078 mm/year in the placebo group compared to 0.0044mm/year in the HRT group, falling below the clinically meaningful threshold Dr Hodis himself previously stated. This calls into question whether the findings have any real-world implications for reducing cardiovascular events.

The ELITE study delivered what many consider the final blow to the timing hypothesis. While it showed statistically significant changes in CIMT progression with early oestradiol therapy, these changes were clinically negligible, falling short of proving any meaningful cardiovascular benefit. By failing to provide definitive evidence, ELITE cast a long shadow over the idea that early initiation of HRT could prevent cardiovascular disease, leaving the timing hypothesis on shaky ground and largely unsubstantiated.

This argument is bolstered by the FDA, which has steadfastly maintained its warnings on HRT since the WHI study, despite repeated calls from some clinicians to ease these restrictions – if even for low-dose HRT. The FDA has consistently refused these appeals, citing the robust evidence from the WHI study that highlights the risks associated with HRT.

According to the agency, no new evidence has emerged to overturn these findings, reaffirming the conclusion that the current data does not support the safety of HRT. This stance further prompting continued caution in prescribing HRT, with the absence of definitive new evidence to justify its widespread use as a cardioprotective agent.

The current consensus on HRT use

In light of the controversies and evidence presented by studies like WHI, HERS, KEEPS, and ELITE, the medical community has reached a broad consensus regarding the appropriate use of HRT. Virtually every major guideline, including those from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, the North American Menopause Society, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology, the Endocrine Society, and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), converges on the following points:

- HRT should be used primarily for managing menopausal symptoms, such as vasomotor symptoms and vaginal dryness, when they significantly impact quality of life.

- HRT is not recommended for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease or other chronic conditions.

- Women with high cardiovascular risk or established cardiovascular disease should avoid HRT due to the potential for harm.

The ESC specifically underscores the importance of avoiding HRT in women with a history of cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarction or stroke. Additionally, they emphasise caution even in asymptomatic women, reflecting the unresolved safety concerns surrounding HRT’s broader health implications.

Shared decision-making: A key to HRT use today

Despite these stringent guidelines, the decision to initiate HRT ultimately rests on shared decision-making between the clinician and the patient. Recent consensus statements, including a 2023 consensus in Circulation, reaffirm that HRT should be individualised based on the patient’s symptoms, health profile, and personal preferences.

Patients should not be misled into believing that HRT provides protection against cardiovascular or other chronic diseases, nor should it be portrayed as a universal solution for post-menopausal longevity or vitality. Instead, clinicians are urged to set realistic expectations, empowering women to make informed choices aligned with their values and priorities.

Moving forward: The role of evidence-based medicine

While HRT remains an important tool for managing menopause-related symptoms, its use for broader health benefits, particularly cardiovascular prevention, has been consistently refuted by robust evidence. The medical community continues to await well-designed trials that could provide definitive answers about the timing hypothesis or other potential benefits of HRT in specific populations.

Until such data emerges, the recommendations remain clear: HRT should be reserved for managing menopausal symptoms, with careful consideration of individual risk profiles.

While transdermal oestrogen and bioidentical HRT are often marketed as safer alternatives to traditional oral HRT, no high-quality RCTs have validated these claims. Although observational studies have suggested potential benefits, history serves as a cautionary reminder. Observational data once misled the medical community into believing oral HRT was cardioprotective, only for large-scale RCTs like WHI and HERS to decisively disprove those assumptions. Until rigorous clinical trials confirm the long-term safety and efficacy of transdermal and bioidentical formulations, their presumed advantages remain speculative rather than evidence-based.

In conclusion, the journey of HRT is a testament to the evolving nature of medical science. From its rise as a revolutionary treatment to its scrutiny under the lens of rigorous evidence, HRT continues to serve as both a critical option for managing menopausal symptoms and a subject of ongoing debate.

As we move forward, the focus must remain on patient-centred care, guided by robust scientific evidence and open, informed discussions. Only through this approach can we balance the promise of HRT with its risks, ensuring it serves as a tailored ally rather than a misunderstood foe.

References available on request