While psoriasis is now recognised as often presenting with significant comorbidities, and is still without a cure, much can be done today to help control the condition

Psoriasis is a common, chronic, often disfiguring skin condition affecting 2-to-3 per cent of the Irish population. Males and females are equally affected. Initial presentation is usually in the late teens to early 20s. Around 75 per cent of cases occur before the age of 40. There is a second peak in presentation, involving a smaller group of patients, over the age of 50.

Over the years, it has become increasingly evident that psoriasis is not only a skin disease. Systemic comorbidities include arthritis, cardiovascular disease, obesity, fatty liver disease, anxiety, and depression. Recent therapeutic advances with targeted biological drugs have revolutionised the management of severe psoriasis. Unfortunately for the two-thirds of affected individuals with mild psoriasis, we have not witnessed similar advances in topical therapies. Nevertheless, primary care has much to contribute to the ongoing care of psoriasis patients.

Disease activity fluctuates unpredictably over the years – 10-to-15 per cent of patients get a period of remission of five years or more. While we do not have a cure, there is much that can be done to help control the condition. Even though treatment regimens may be messy and give variable results, a cautiously optimistic approach should be adopted when managing individuals with mild psoriasis presenting in primary care.

It follows that GPs need to have a good understanding of psoriasis, the treatment options available in primary care, possible comorbidities, and recognise when it is appropriate to refer to secondary care.

CLASSIFICATION OF PSORIASIS

- Chronic plaque

- Scalp

- Facial

- Flexural

- Genital

- Nail

- Guttate

- Palmoplantar pustulosis

- Erythrodermic

- Generalised pustular

FIGURE 1: Psoriasis subtypes

Symptoms and signs

In the past psoriasis was considered a non-pruritic condition. In fact, itch is common although generally it is less marked than in eczema.

As psoriasis is a clinical diagnosis, careful examination of the presenting lesions is most important. Chronic plaque psoriasis is the most common form of psoriasis, accounting for up to 90 per cent of cases. Individual lesions are sharply demarcated, thickened, salmon-pink plaques that are covered in scales, which can be fine and silvery, or thick, yellow, and adherent.

Plaques are symmetrically distributed, most commonly over the elbows, knees, lower back, umbilicus, and natal cleft. Plaques range from small, guttate type (<1cm) lesions to extensive confluent plaques. The extent of skin disease can fluctuate over months or years. After clearance there can be post-inflammatory erythema that persists for several months. Post-inflammatory hypo- and hyper-pigmentation are common in patients with skin of colour (Image 9).

Auspitz sign helps distinguish psoriasis from other rashes (Image 4 and Image 5). Scratching a plaque lifts the silvery scale, making it more apparent. Lifting large scales may cause capillary bleeding.

Plaques in body flexures (inverse pattern psoriasis) such as the axilla, gluteal fold, or under the breasts, have little or no scale and the plaques are thinner. These changes in clinical presentation are due to occlusion where skin meets skin. Plaques have a glazed appearance, a sharply defined margin, and an exudate may be present (Image 2).

Classification of psoriasis can be confusing. All plaques are essentially similar, involving inflammation and hyperproliferation of the skin. The classification in Figure 1 is based on the body area involved. Clinical features vary accordingly, eg, plaques in flexural sites, where skin meets skin, do not show scale, and are thinner than plaques over the knees, elbows, etc (Image 1).

The site of skin involvement will also affect our choice of treatment, eg, potent topical steroids may be used for psoriasis over the elbows, trunk, or knees, but only mild or moderate steroids should be used in flexural areas such as the axilla and groin.

TRAUMA

Psoriatic plaques may develop at sites of skin injury – the Koebner phenomenon.

INFECTION

Streptococcal throat infection triggers 60 percent of guttate psoriasis. It may also cause flare-ups of chronic plaque disease. Tonsillectomy may be considered if the problem recurs. HIV infection may trigger or exacerbate psoriasis.

SUNLIGHT

Most psoriasis improves on exposure to sunlight, but in 10 per cent sunlight can cause a flare of disease. Patients should be warned that psoriasis may spread to sunburned areas ( Koebner phenomenon ).

STRESS

In surveys, patients repeatedly report that they find that stress exacerbates their psoriasis. As it is such a stressful condition, it is often not clear which came first.

ALCOHOL EXCESS AND SMOKING

Psoriasis patients consume more alcohol and smoke more than their peers. Whether they have a causal role, or just reflect increased stress, is not clear. Smoking does increase the risk of developing palmoplantar pustulosis and stopping smoking may resolve the problem.

DRUGS

Lithium, anti-TNF drugs, and chloroquine may trigger exacerbations of psoriasis, although most patients can take these medications without effect on their disease. Withdrawal of systemic or super-potent TCS may cause a flare of psoriasis, especially if patients have been on them for some time.

TRAUMA – Psoriatic plaques may develop at sites of skin injury – the Koebner phenomenon.

INFECTION – Streptococcal throat infection triggers 60 per cent of guttate psoriasis. It may also cause flare-ups of chronic plaque disease. Tonsillectomy may be considered if the problem recurs. HIV infection may trigger or exacerbate psoriasis.

SUNLIGHT – Most psoriasis improves on exposure to sunlight, but in 10 per cent sunlight can cause a flare of disease. Patients should be warned that psoriasis may spread to sunburned areas (Koebner phenomenon). (Image 3)

STRESS – In surveys patients repeatedly report that they find that stress exacerbates their psoriasis. As it is such a stressful condition it is often which came first.

ALCOHOL EXCESS AND SMOKING – Psoriasis patients consume more alcohol and smoke more than their peers. Whether they have causal role, or just reflect increased stress, is not clear.

Smoking does increase the risk of developing palmoplantar pustulosis and stopping smoking may resolve the problem.

DRUGS – Lithium, anti-TNF drugs, and chloroquine may trigger exacerbations of psoriasis, although most patients can take these medications without any effect on their disease. Withdrawal of systemic or super-potent TCS may cause a flare of psoriasis, especially if patients have been on them for some time.

FIGURE 2: Triggers of psoriasis

Aetiology

The exact cause of psoriasis is not fully understood, but involves a complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors. Lymphocytes release cytokines, interferon alpha, interleukin, and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) that result in overgrowth of the epidermis (resulting in thick, silvery scaled plaques), capillary proliferation, and inflammation (giving a red colour).

There has been a steady increase in the number of effective biological therapies targeting the body’s immune response available in secondary care. While they are expensive, they can give dramatic improvement in disease control.

A family history of psoriasis occurs in about 30 per cent of patients. Monozygotic twins have a two-to-three-fold increased risk of psoriasis compared with dizygotic twins. If one parent has psoriasis, there is a 14 per cent risk of their child developing it. If both parents are affected the risk is 41 per cent. If one sibling has psoriasis the risk is 6 per cent. Various triggers may trigger or exacerbate psoriasis (see Figure 2).

| TREATMENT | ADVANTAGES | PROBLEMS |

|---|---|---|

| Emollients | Low side-effect rate, cheap | Limited efficacy when used alone |

| Tar | Effective. Tar extracts less effective, but easier to use | Messy, smelly. Irritation |

| Dithranol | Short contact is effective and safe | Stains skin and anything it comes in contact with. Skin irritation |

| Corticosteroids (TCSs) | Effective, easy to use | Skin atrophy, bruising, striae. Rebound of psoriasis on stopping |

| Vitamin D analogues | Effective, easy to use | Skin irritation |

| Tacrolimus | Very effective on thin plaques only | Need sun protection and avoidance. Burning sensation for first five days of application. Not a licensed psoriasis treatment |

FIGURE 3: Topical treatments available for psoriasis

Differentiating psoriasis from eczema

- The well-demarcated edge is probably the most distinguishing feature of psoriasis (Image 5). The edge of a patch of eczema is more diffuse.

- Scratching a plaque of psoriasis makes the silvery scale more obvious.

- Patches of chronic eczema show lichenification; ie, skin thickening with exaggeration of skin markings.

- Psoriasis has a characteristic distribution pattern on the extensor surfaces, especially on the elbows and knees, and on the scalp. Atopic eczema favours the flexural surfaces of elbows and knees.

- The Koebner phenomenon, that may be seen in psoriasis, does not occur in eczema.

Management of psoriasis in primary care

Advances in biological therapies have revolutionised management in secondary care. Huge resources have been invested in the development of these targeted therapies. No such effort is apparent to find new, effective, and acceptable treatments for the majority of patients with milder disease. Psoriasis therefore remains a difficult-to-treat condition in the primary care setting. What constitutes an acceptable level of control is very subjective. Many find topical therapies burdensome and results may be limited.

Before making a shared decision on a treatment plan, explore the patient’s knowledge, hopes, and expectations, and to what extent psoriasis impacts their daily life. There is much that we can do to help our patients deal with their disease and a positive, realistic attitude should be maintained. All patients need time to discuss the condition. Information can be supplemented by patient information leaflets.

Patients need to accept that they have a chronic condition that cannot be cured and will require long-term management. The effects of psoriasis on work, personal relationships, and social life should be explored. Many patients need to hear that psoriasis is not infectious. In recent years the Psoriasis Association has been very active in providing advice, education, and support to patients. All patients should consider joining the association.

Primary care treatments

Emollients

Emollients are often forgotten when treating psoriasis. All patients should

be advised to use emollients liberally, daily. Emollients help moisturise plaques and reduce scaling. They may make it more comfortable and less obvious. Many patients are happy with this level of improvement. Patients need to try a few different emollients to find which one combines acceptability with effectiveness for them. All patients suffering from psoriasis should be prescribed sufficient emollient to allow frequent, generous application.

Tar

Tar has long been used to treat psoriasis and still has a place today. It can be used as crude coal tar or tar extracts. Crude coal tar is messy, inconvenient, and smelly. There are several commercial preparations of tar extracts available as creams, lotions, and shampoos. These are less effective than crude coal tar, but more convenient and pleasant to use. There is no evidence that therapeutic use of tar products causes skin or internal cancer.

Dithranol

Like tar, dithranol is a long established, effective, and safe topical therapy for psoriasis. With short contact dithranol therapy, it is left on the skin for 20-to-30 minutes before being washed off. It is effective in 50-to-60 per cent of patients and some achieve a prolonged remission. It can cause skin irritation and pigmentation. It stains any surface it comes in contact with. In the past it was available in various strengths (dithrocream 0.1 per cent, 0.25 per cent, 0.5 per cent, 1 per cent, and 2 per cent). Recently a 15 per cent non-licensed preparation has been available.

Topical corticosteroids

Topical steroids are easy to prescribe and pleasant to use. Their use in treating plaque psoriasis was controversial up to recent years and indeed their use was once frowned upon. NICE guidelines in the UK give the use of topical corticosteroid (TCSs) in psoriasis a favourable recommendation.

Problems with their use include:

- Side-effects on the skin – atrophy, telangiectasia, bruising (Image 7).

- Steroids sometimes seem to change the nature of the disease making it unstable. Unstable psoriasis looks red and angry. In this state it is difficult to treat. If calcipotriol, tar, or dithranol are applied they may exacerbate the irritation. The risk is greatest when a potent or very potent topical steroid has been applied for some time and then suddenly stopped. In extreme cases generalised pustular psoriasis may be precipitated. When plaques of psoriasis are irritated and acutely inflamed it is best to apply generous amounts of emollient until the disease again stabilises (the plaques regain their pink colour and are covered with silvery scales). Patients with more widespread unstable disease and those with generalised pustular psoriasis require urgent referral.

- Tachyphylaxis – extended use of TCSs give less and less of a therapeutic response. This happens with all potencies of steroid. To avoid this phenomenon continuous application of TCSs should not be continued for longer than one month.

TCSs are best used in combination with other topical therapies to bring about a speedy clinical improvement. There is evidence that the best results when treating plaque psoriasis are with a combination of a vitamin D analogue with betamethasone (dovobet). Combining a topical steroid with tar or dithranol gives better results than either used alone. Combination therapy is continued for one month at which point the topical steroid should be stopped or used only intermittently.

Vitamin D analogues

Vitamin D analogues are usually combined with a potent TCS in fixed-dose combination products. The fixed combination products containing calcipotriol plus betamethasone (enstilar foam, dovobet gel, dovobet ointment) are often used as a first-line option for chronic plaque psoriasis.

Another fixed-combination product more recently available in Ireland combines calcipotriene and betamethasone dipropionate (wynzora cream). It is an option if the patient prefers a less greasy preparation. These applications do not stain, are easy to use, and are usually well tolerated. Because of their ease of use they are the treatment of choice when managing chronic plaque psoriasis in primary care, involving less than 30 per cent of the body surface.

When the psoriasis plaques are flat, and the skin feels smooth to touch, these products should be stopped. Some patients may need to continue applying them once or twice weekly to maintain response. As they each contain a potent topical steroid, they should not be applied to the face, flexures, or genitalia.

Calcineurin inhibitors

Tacrolimus (protopic) is the only calcineurin inhibitor available in Ireland. It is very effective on thin plaques of psoriasis. Best results are with the 0.1 per cent ointment preparation. Such plaques are found on facial, genital, and flexural areas.

Calcineurin inhibitors are immunosuppressant and, in theory, might interfere with skin repair after ultraviolet light damage. Although photoprotection and sun avoidance are advised, long-term studies have shown no increase in either skin or internal cancer with tacrolimus.

A burning sensation at the site of application for the first five days of treatment is common, but settles if treatment is persevered with. Using tacrolimus to treat psoriasis is off label. Patients should be advised of this.

Flexural psoriasis

Essentially flexures are areas of the body where skin meets skin. This creates an occlusive effect that affects both the presentation and the management of psoriasis. Flexures that may be involved in psoriasis include the axilla, gluteal cleft, umbilicus, under the breasts, retro auricular fold, skin folds, and the inguinal crease. This pattern is also referred to as inverse pattern psoriasis. Plaques are sharply demarcated, thin, and have little or no scale. They are pink-to-red in colour and have a shiny, glazed appearance. An exudate may be present.

Facial and genital skin is thin and the treatment regimen for both areas is similar to that for flexural psoriasis. Patients should be asked if they have flexural or genital involvement as very often, they will not volunteer this information. Great psychosocial distress may ensue when such areas are involved.

Emollients are always advised. Potent and very potent corticosteroids risk skin atrophy on flexures, the face, and genitalia, and should be avoided. Hydrocortisone is generally not very effective. The moderate potency clobetasone butyrate (eumovate) is the best choice, combining efficacy with safety. The ointment formulation is favoured. It can be combined with calcipotriol ointment (dovonex). One can be applied in the morning with the other at night.

Tacrolimus (protopic) is ineffective on the thick lesions of chronic plaque psoriasis. In contrast, the thin plaques and the occlusive effect in flexures enhance drug penetration and effectiveness. Studies have shown a response rate of 90 per cent, far better than many of our other treatment options. They remain unlicensed for use in psoriasis.

Scalp psoriasis

Scalp involvement (Image 6) is common and may sometimes be the only manifestation of the disease. Up to 80 per cent of psoriasis patients have scalp involvement. In 40 per cent of these it involves more than half of the scalp surface. The prevalence of scalp involvement increases with duration of the disease.

Treatment requires getting through a thick coverage of scalp hair necessitating non-messy solutions. This is difficult to achieve with creams, ointments, and especially pomades. Patient compliance and tolerability can play a crucial role in successful management. Patients prefer gels, lotions, and foams. Oils and creams are less acceptable, with ointments the least attractive option. Therefore, when it comes to treatment, choice of vehicle can be as important as the choice of therapy itself.

Two approaches have been adopted in an attempt to improve acceptability and effectiveness of topical treatment:

1) Reduce messiness of treatment: Cocois contains tar and salicylic acid. It has a bit of a smell, but is generally well-tolerated. It can be applied at night and washed out in the morning, longer than recommended by the manufacturers.

2) Combine treatments: Combine TCS and tar – Cocois can be applied as above. After washing it out in the morning a steroid scalp application is applied.

Combine TCS and a vitamin D analogue; eg, Dovobet gel. It is applied at night to the scalp and washed out in the morning.

If the scalp disease is hyperkeratotic the thick scales need to be softened and removed. Arachis oil, coconut oil, or olive oil may help. Coconut oil is easy to apply to scalp plaques and can be left on for 30 minutes or overnight. A comb can then be used to gently lift off the softened plaques. The hair is then washed with tar-based shampoo.

Pregnancy and psoriasis

Psoriasis generally tends to improve during pregnancy, but may sometimes flare. Exacerbations often improve after delivery. Topical vitamin D analogues and TCSs are safe in pregnancy. Use the least potent TCS application.

Comorbidity in psoriasis

Psoriasis is now established as a systemic, inflammatory disease not just involving the skin. Common systemic manifestations include:

- Cardiovascular disease;

- Depression;

- Psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

GPs are ideally placed to assess and manage multimorbidity and are best placed to provide and co-ordinate care for this group of patients.

TREATMENT OF CHRONIC PLAQUE PSORIASIS

First-line – Once daily calcipotriol plus betamethasone (ensilar foam, dovobet gel, dovobet ointment) or calcipotriene plus betamethasone dipropionate (wynzora cream)

Second-line – Betamethasone ointment am + tar preparation

(exorex lotion) pm

Third-line – Betamethasone ointment am + short contact dithranol therapy pm

FACE, FLEXURES, GENITALIA

First-line – Clobetasone butyrate (eumovate) ointment am + calcipotriol ointment

(dovonex) pm

Second-line – Tacrolimus 0.1 per cent (protopic) once daily

SCALP

First choice – Dovobet gel pm

Second-line – Cocois pm plus betamethasone scalp application am

FIGURE 4: Treatment algorithm for topical treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis

- ► Inadequate response to topical therapy – emollients, vitamin D analogues, and TCSs

- ► Psoriasis covering more than 15-to-20 per cent of the body surface

- ► Widespread unstable or erythrodermic psoriasis

- ► Generalised pustular psoriasis

- ► PsA

- ► Disease severity causing unemployment

- ► Marked psychosocial impact

FIGURE 5: When to consider referral to secondary care

Cardiovascular disease

In recent years repeated studies have confirmed that there is an association between psoriasis and the metabolic syndrome diabetes mellitus, obesity, heart failure, and hypertension. As a consequence, psoriasis patients are at increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (five-fold), myocardial infarction (two-to-three-fold), and have a life expectancy four years shorter than healthy controls. Psoriasis is now established as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease should be addressed. The level of risk correlates with the severity of psoriasis.

All psoriasis patients should have:

- Advice on a healthy diet and maintaining a healthy weight. Obesity seems to increase the risk of psoriasis and reduce the effectiveness of treatment. Losing weight seems to increase treatment effectiveness.

- Regular blood pressure checks.

- Waist measurement.

- Body mass index (BMI) measurement.

- Advice on smoking cessation.

- A random HbA1C (or fasting glucose) and fasting lipids should be checked if the BMI is greater than >25 or the waist circumference is greater than 80cm or there is a first-degree relative with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Depression

There is a significant psychiatric and psychosocial morbidity risk in psoriasis patients. It has been shown that there is a 6 per cent prevalence of active suicidal ideation (versus 2.4-to-3.3 per cent in general medical patients). Psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory disease. Inflammatory mediators such as TNF mediate depression. It is of interest that anti-TNF therapies have shown promising antidepressant activity in clinical trials. Patients’ mood, and their feelings regarding their disease and its management, should regularly be discussed.

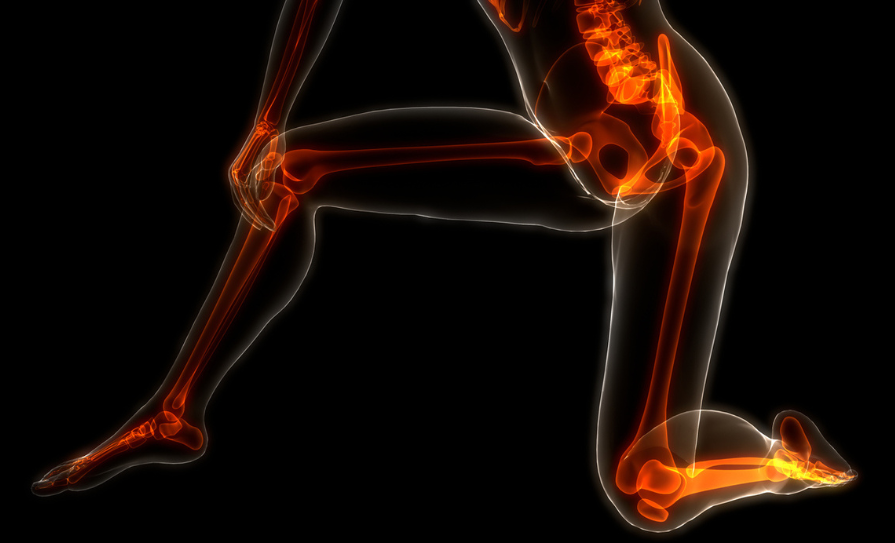

Psoriatic arthritis

PsA (Image 8) develops in up to 30 per cent of patients with psoriasis, presenting as a range of destructive inflammatory arthropathies. Up to 50 per cent of patients who develop PsA develop persistent inflammation. If untreated, progressive joint damage results in severe physical limitations and disability. Early signs include joint pain, morning stiffness, enthesitis (inflammation of the tendon and ligament attachments to bones), and dactylitis (swollen, sausage-like swelling of digits). Prevalence increases with more extensive disease.

As it is a seronegative, PsA is difficult to diagnose. Always ask patients about joint pains and morning stiffness when reviewing them. Early diagnosis and referral for consideration of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs is essential if PsA is suspected.

Five patterns of PsA:

- Distal interphalangeal arthropathy – 5-to-10 per cent – primarily in men;

- Symmetric polyarthritis resembling rheumatoid arthritis – often relatively asymmetrical and may involve distal interphalangeal joints;

- Asymmetric oligoarthritis – 30 per cent – (typically involvement of a large joint, eg, knee, plus a few small joints of the hands or feet);

- Spondyloarthropathy (± sacroiliitis);

- Arthritis mutilans – destructive arthritis affecting the hands and feet.

Unfortunately, in recent years the availability of some topical therapies has not been reliable and all prescribers need to be aware of what is available when writing their prescriptions (see Figure 4).

The exact cause of psoriasis is not fully understood, but involves a complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors