Reference: Mar-Apr 2023 | Issue 2 | Vol 16 | Page 18

Start this Module

Module Title

Diagnosis & management of asthma in adults & adolescentsModule Author

Dr Shane Brennan and Dr Dermot NolanCPD points

2Module Type

TutorialIntroduction

Asthma is a major long-term, non-communicable disease affecting both adults and children. It is the most common chronic disease found in children. In 2019, asthma affected an estimated 262 million people worldwide and was responsible for 455,000 deaths.[1] In Ireland, one-in-13 people have asthma, costing €472 million per annum.

Asthma is included in the World Health Organisation (WHO) Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases and the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Asthma cannot be cured, but it can be managed with appropriate use of medication, allowing patients to enjoy a normal and active life.

In the following CPD module we discuss the diagnosis and management of asthma in adolescents and adults.

Definition

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) defines asthma as a heterogenous disease, usually characterised by chronic airway inflammation. It is defined by a history of respiratory symptoms, such as wheeze, shortness of breath, chest tightness and cough, that vary over time and intensity, together with variable expiratory airflow limitation.[2] Variations in airflow are typically triggered by factors such as exercise, allergen, or irritant exposure, change in weather or viral respiratory infections. Symptoms may resolve spontaneously or in response to medications and be absent for months at a time.

Asthma is a heterogenous disease, however recognisable clusters do emerge based on demographic, clinical and pathophysiological characteristics and are referred to as asthma phenotypes. Some of the most common phenotypes are:

- Allergic asthma: Often commences in childhood and is associated with past and/or family history of allergic disease such as eczema, allergic rhinitis, or food or drug allergy. Patients usually respond well to inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) treatment.

- Non-allergic asthma: Asthma that is not associated with allergy. Patients often display less short-term response to ICS.

- Adult-onset asthma: Asthma which presents for the first time in adult life. Patients tend to be non-allergic and often require higher doses of ICS or are relatively refractory to corticosteroid treatment. Occupational asthma should be ruled out in patients presenting with adult-onset asthma

More recently, there is growing academic endorsement for the classification of asthma into type 2 and non-type 2 asthma. Type 2 inflammation is cell mediated with T helper type 2 cells playing a key role. In response to allergens there is a release of cytokines leading to a cascade of immune responses resulting in inflammation. Typically, type 2 inflammation is linked to eosinophilia and increased IgE. Various conditions including asthma, atopic dermatitis and rhinitis are linked to type 2 inflammation. Usually, type 2 asthma has a good response to ICS. Severe asthma with type 2 inflammation is associated with a higher risk of exacerbation, hospitalisation, and death than if type 2 inflammation is not present. It is this group that is being targeted for new biological therapies for asthma. Dupilumab, for example, was endorsed in the UK by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellent (NICE) in December 2021 and is licensed for treating severe asthma with type 2 inflammation.[3]

Diagnosis

Making a diagnosis of asthma in a patient not on controller treatment is based on recognising both a characteristic pattern of respiratory symptoms and demonstrating variable expiratory airflow limitation.[4] Typical respiratory symptoms include cough, wheeze, dyspnoea and/or chest tightness. Symptoms are often worse at night or early morning. Symptoms vary over time and in intensity. Symptoms are precipitated by viral infections, exercise, allergen exposure, changes in weather, or irritants such as cigarette smoke or exhaust fumes.

Once a classical pattern of respiratory symptoms has been recognised it is important to confirm the diagnosis of asthma with documentation of variable expiratory airflow limitation. This is to avoid unnecessary treatment or over treatment, and to avoid missing alternative diagnoses. A recent study of patients aged 18 years and over with a diagnosis of asthma in the previous five years found that when subjected to spirometry, 33 per cent had asthma excluded.[5] Similarly, approximately 50 per cent of children diagnosed with asthma have been found to have been incorrectly diagnosed.[6]

Confirmation of variable expiratory airflow limitation is a two-step process. First, expiratory airflow limitation should be documented. At a time when FEV1 is reduced, confirm that FEV1/FVC is reduced compared to the lower limit of normal, ie, >0.75-0.80 in adults and >0.90 in children. Second, excessive variability in lung function should be documented, ideally via a bronchodilator (BD) responsiveness test. This is deemed to be positive when there is an increase in FEV1 of ≥12 per cent and ≥200ml measured 10-15 minutes post 200-400mcg salbutamol, compared with pre-bronchodilator readings.

If spirometry is not available excessive variability can be demonstrated by diurnal peak expiratory flow (PEF) measurement over two weeks. This is positive if the average daily diurnal PEF is >10 per cent in adults and >13 per cent in children. Diurnal PEF variability is calculated from twice daily readings as the daily amplitude percent mean, ie ([day’s highest – day’s lowest]/mean of day’s highest and lowest) x 100.

If possible, variable expiratory airflow limitation should be documented before treatment is initiated because variability typically decreases with ICS treatment as lung function improves.

Management of asthma

Medications for the management of asthma can be divided into two broad categories: controller medications and reliever medications.

Controller medications contain ICS. They reduce airway inflammation, control symptoms, and reduce future risks of exacerbations and decline in lung function.

Reliever medications are used for as-needed relief of breakthrough symptoms, including during worsening asthma or exacerbations.

In 2019 GINA endorsed a fundamental change in asthma management when it made a recommendation against the treatment of asthma in adults and adolescents with a short-acting beta agonist (SABA) alone.[7]

Low-dose ICS-formoterol as a reliever is now the preferred approach recommended by GINA. When a patient at any step along the treatment ladder has asthma symptoms they should use ICS-formoterol as needed for symptomatic relief. In addition, patients on Steps 3-5 of the GINA treatment ladder should take ICS-formoterol as regular daily treatment. This is known as low-dose ICS-formoterol as maintenance and reliever therapy (MART).

Where ICS-formoterol as reliever is not possible, GINA recommends that for those patients with mild asthma on a SABA as-needed therapy alone, they should have a low-dose ICS added to their therapy, to be taken in combination with, or right after, the SABA for symptomatic relief.

The recommendation by GINA for extending the recommendation for as-needed ICS-formoterol stemmed from several considerations. Patients with mild asthma and infrequent symptoms can still have severe or fatal exacerbations.[8] A single day with increased as-needed ICS-formoterol reduces the short-term risk of severe exacerbation compared with SABA use alone.[9] GINA points out that recommending patients be provided with a controller medication from the outset of management allows for consistent messaging. It avoids the scenario previously, where a patient starts out on a SABA alone and then is asked to add a daily controller despite treatment being adequate from the patient’s perspective, thus avoiding overreliance on SABA as the main asthma treatment.

The usual dose of as-needed budesonide-formoterol in mild asthma is a single inhalation of 200/6mcg. The maximum recommended dose of as needed budesonide-formoterol in a single day corresponds to a total of 72mcg formoterol (12 inhalations of budesonide-formoterol 200/6mcg). ICS-formoterol formulations other than budesonide-formoterol have not been studied for as-needed only use, but beclomethasone-formoterol may also be suitable. Rinsing the mouth is generally not needed after as-needed use of low-dose ICS-formoterol.

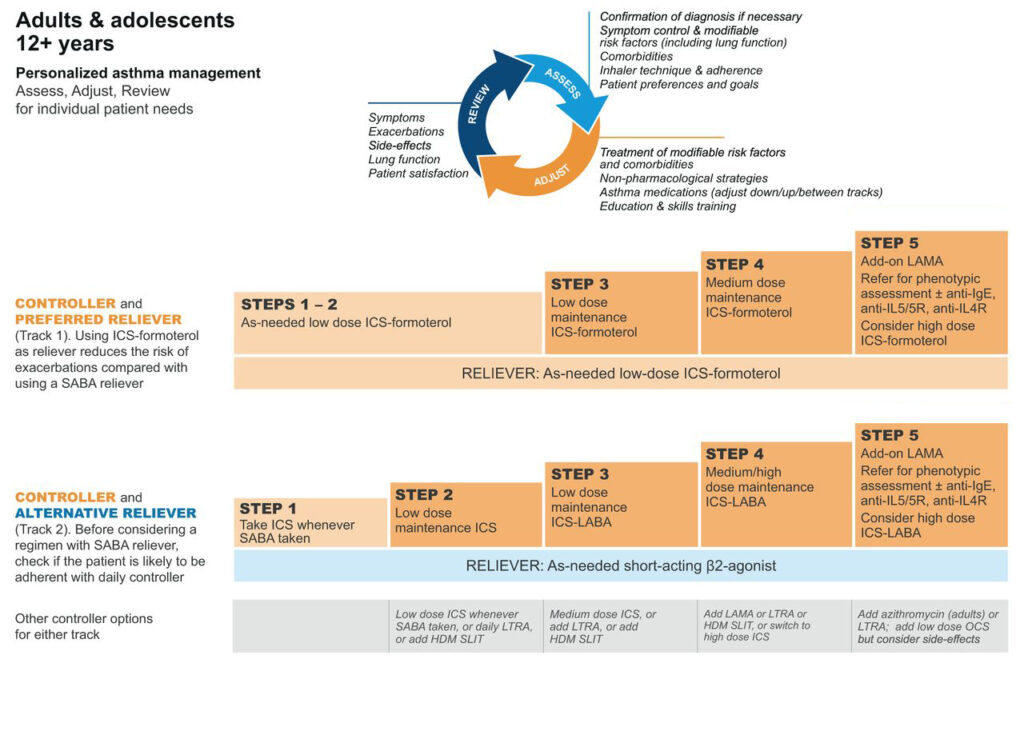

Figure 1 below sets out the step-wise approach recommended by GINA to the management of asthma.

Figure 1. Medication management of asthma of asthma in adults and adolescents >12 years. GINA 2022

Steps 1-2 refers to patients who experience symptoms less than four-to-five days a week. As discussed above, GINA recommends as-needed ICS-formoterol for steps 1-2.

Step 3 refers to patients who experience daily symptoms or wake from sleep due to asthma once a week or more. These patients should be commenced on regular low-dose ICS-formoterol as maintenance in addition to reliever therapy, ie, MART.

Step 4 refers to those patients who experience daily symptoms or wake from sleep once a week or more and exhibit low lung function. GINA recommends in such patients increasing to medium-dose ICS-formoterol.

Step 5 refers to those with severe, uncontrolled asthma. These patients will require referral to specialist clinics with access to biologic therapies including anti-IgE (omalizumab), anti-IL5 (mepolizumab), anti-IL5R (benralizumab), anti-IL4 (dupilumab) and oral corticosteroids.

Note that for all treatment steps GINA highlights that leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRA) and sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) are potential alternative controller options. Immunotherapy involves desensitisation to specific allergens and works by reducing the inflammatory response to the sensitised antigen. SLIT involves delivering desensitising doses of an antigen under the tongue. Currently in Ireland, SLIT is limited to grass pollen allergy, however, house dust mite and tree pollen therapies are in development.

Once asthma treatment has been commenced, controller treatment should be adjusted up or down in a step-wise approach to achieve good symptom control and minimise risk of exacerbations. Once good control has been achieved for two-to-three months, treatment may be stepped down to find the patient’s minimum effective treatment.

If a patient has ongoing poor symptom control despite two-to-three months of controller treatment, assess for any modifiable factors before stepping up treatment. Common causes for poor symptom control include poor inhaler technique, poor adherence to treatment, persistent exposure to allergens such as cigarette smoke and air pollution, or to medications such as beta-blockers and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Asthma and Covid-19

People with asthma do not appear to be at increased risk of contracting Covid-19 and studies do not indicate that people with well-controlled asthma are at increased risk of Covid-19-related death.[10] However, the risk of Covid-19-related death was increased in those who recently required oral corticosteroids for their asthma.[11] Therefore, it is essential to continue good asthma management through the maintenance of good symptom control and the minimisation of oral corticosteroid use. It is essential that patients continue to take asthma medications as prescribed, including ICS. Stopping ICS can lead to potentially dangerous worsening of asthma.

Written asthma actions have added importance in the context of Covid-19. These enable the patient to recognise the symptoms of worsening asthma, how to increase medications, and when to seek medical help.

Nebulisers can transmit respiratory viral particles up to one metre. Use of nebulisers should be restricted to the management of life-threatening asthma exacerbations in acute care settings. In all other instances, SABA for acute asthma should be delivered via a pressurised metered-dose inhaler and spacer with a mouthpiece and tightly-fitting face mask.

Conclusion

Asthma is one of the most common chronic respiratory conditions, with burdensome implications in terms of morbidity for the patient and cost to the State. The first step in reducing this burden is for clinicians to be able to recognise the classical respiratory symptom patterns of asthma, allied to objective documentation of variable expiratory airflow limitation to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment of asthma has evolved over the last number of years. Chief among this being GINA’s recommendation that ICS-formoterol form the cornerstone of asthma management. New biological and immunological therapies are now entering the management protocol across all severities of asthma, which will further reduce the symptom burden on patients.

Clinicians should strive to implement and encourage adherence to personalised asthma management plans, particularly in the context of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.