Reference: Jan-Feb 2024 | Issue 2 | Vol 17 | Page 42

Exploring the four most common differential diagnoses for chronic cough seen in primary care

Effective clinical decision-making promotes positive patient outcomes and quality patient care. Decision-making is a complex process. It encompasses history taking, assessment of patients’ pathological conditions, and the use of evidence-based knowledge to make decisions and action outcomes.

Patient presentations can often have several differential diagnoses, and clinicians can utilise evidence-based algorithms to guide and support clinical decision-making processes.

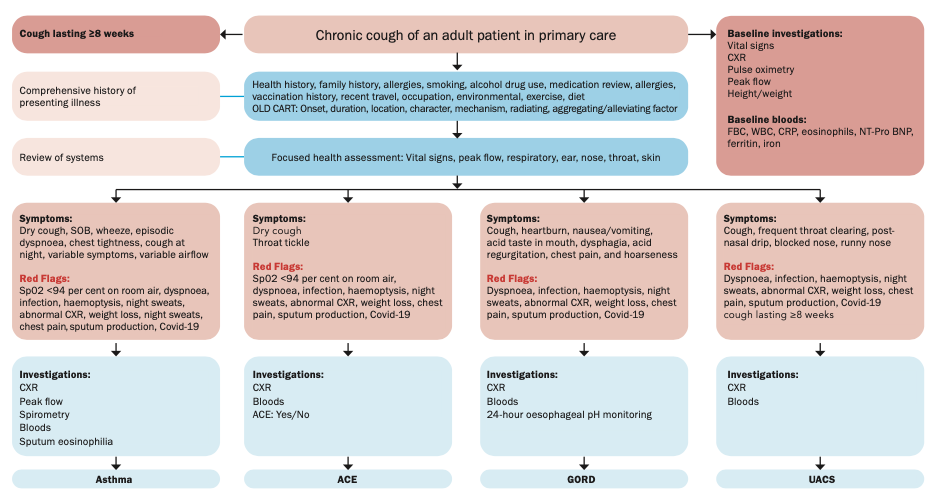

This article and algorithm aim to provide a systematic approach to identifying the cause of a chronic cough presenting in an adult patient attending primary care. Four differential diagnoses commonly seen in primary care will be considered and discussed, with a rationale provided for the final clinical diagnosis of the patient.

Patient case

A 55-year-old male patient with known hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia attended the surgery for a routine review and blood pressure check. The patient reported a chronic cough, which he described as “a dry cough, present for approximately 10 weeks and worse at night”. He “thought it would go away”, but symptoms have persisted, and he is “worried something serious is wrong”. The history of presenting illness (HPI) was established using the OLD CARTS mnemonic.21 A focused health history, vital signs, and physical examination were carried out. Routine bloods and a chest x-ray were obtained.

Chief complaint

Symptoms have been persistent for about 10 weeks. The dry cough is disturbing his sleep, and he feels tired and lethargic. The patient describes the cough as “dry and irritating”, which is worse at night, and keeps him awake. He quickly gets short of breath and coughs on exertion and exercise. Symptoms subside with rest. He has noticed occasionally that aerosols and sprays can make him cough.

He denies chest pain, temperatures, sputum production, haemoptysis, night sweats, nausea/vomiting, heartburn, difficulty swallowing, or weight loss. He has been treated in the past year for a chest infection with antibiotics, steroids, and a salbutamol inhaler. He has had no sinus infections, and no increased nasal secretions. He had a Covid-19 infection some 18 months ago. He is a lifelong non-smoker. He takes antihistamines in the summer for hay fever.

Physical assessment

Vital signs were taken. BP 137/81; pulse 90, sinus rhythm, respiratory rate of 22/min; Sp02 98 per cent on room air; reduced peak flow of 420l/min. A physical examination was carried out. The ‘inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation’ approach guided the respiratory assessment.21 The patient was talking in complete sentences. No increased work of breathing was observed. This is observed by the paradoxical movement of the abdomen.21 No increased use of accessory muscles.

The patient had no signs of cyanosis or pallor. No clubbing of extremities was observed. Clubbing is a sign of chronic hypoxia and is often seen in malignancies and conditions that affect circulation.22 Thorax was symmetrical with good expansion. Fremitus sounded unremarkable. Asymmetric, decreased, or absent fremitus can suggest other lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, malignancy, and pneumonia.21 On percussion, this patient’s chest was resonant. Percussion helps establish if the lungs are air/fluid filled or consolidated.

On auscultation, the patient had vesicular breath sounds with slight expiratory wheeze heard throughout lung fields, which is suggestive of asthma due to the narrowing of the airways. However, other conditions can cause localised or scattered wheezes, such as foreign bodies, mucus plugs, and tumours.21 The ears, nose, and throat were also examined for any other possible causes of a chronic cough, and no further findings were conducive. This patient had a negative Covid-19 PCR test.

Background

A cough is one of the most common presenting symptoms in primary care. It is a vital protective reflex to prevent lung aspiration. A chronic cough is one that persists for more than eight weeks in adults, and can have a significant impact on a patient’s quality-of-life.

Initial evaluation of patients with a chronic cough usually occurs in primary care. Many causes are identified, including respiratory disease, increased sensitivity of the cough reflex, pathological conditions, lifestyle, environmental, and smoking, to name a few. A chest x-ray (CXR) should be obtained early to exclude malignancy and structural lung disease. Other red flags include infection, haemoptysis, night sweats, CXR changes, abnormal spirometry, dyspnoea, haemoptysis, weight loss, fever, chest pain, or if a patient is immunosuppressed.

Routine blood tests can provide vital information to establish a correct diagnosis and cause of a chronic cough. Full blood count (FBC), white blood count (WBC), c-reactive protein (CRP) to rule out infection, eosinophils (considered in asthma diagnosis), NT-proBNP (considered in heart failure diagnosis), serum ferritin, and iron (because iron deficiency has been associated with chronic cough).

Four of the common causes of chronic cough that present to primary care have been identified as asthma, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD), and upper airways cough syndrome (UACS). The appropriate history, physical examination, diagnostic modalities, and pathological processes for each of the four possible differential diagnoses of the case study patient’s chronic cough are identified as follows:

Asthma

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease that can cause respiratory symptoms including chronic cough with episodic dyspnoea, wheezing, and chest tightness that is often worse at night. Exacerbations can be triggered by exposure to allergens, cold, and fumes.Asthma can limit activity, involve flare-ups that sometimes require urgent healthcare, and can lead to fatality in severe cases. Symptoms are associated with variable expiratory airflow due to bronchoconstriction, airway wall thickening, and increased mucus. Asthma symptoms can be exasperated by factors such as viral illness, allergens (eg, dust mites), smoke, stress, exercise, and some drugs (eg, beta blockers).

Diagnosis is made by a focused history demonstrating variability in the above symptoms, a physical assessment, and spirometry or peak expiratory flow (PEF) test with reversibility. A physical assessment in patients with asthma is often normal, but the most common finding is a wheeze on auscultation. Asthma typically presents with airflow variability and bronchial hyper-responsiveness, therefore, spirometry is a key investigation. However, it is not always routinely available in primary care, so alternatively, an asthma diagnosis can be considered on peak flow variability over 20 per cent in adults.

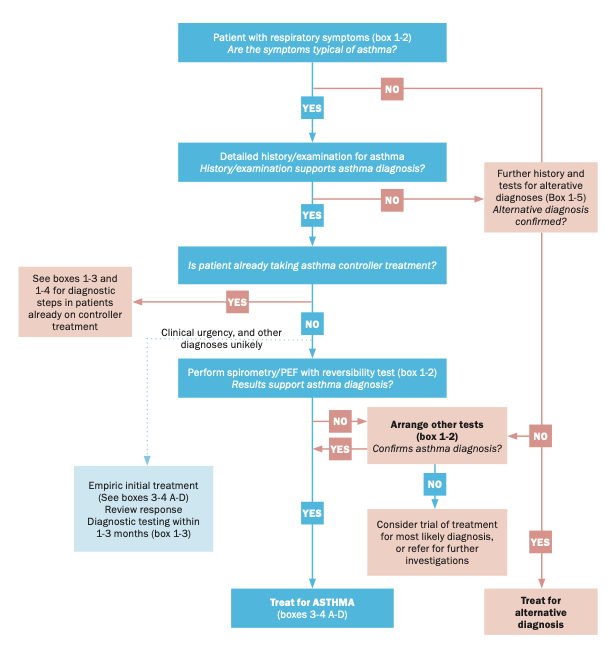

The GINA diagnostic flowchart (Figure 1) can guide the diagnosis of asthma in patients presenting with symptoms. Other evidence of atopy, such as rhinitis, eczema, and an elevated eosinophil count, increase the likelihood of asthma; however, blood eosinophil count does not define asthma, but rather contributes to phenotyping. Sputum eosinophilia is generally more accurate, but is not routinely available in primary care.

Figure 1: The GINA diagnostic flowchart 2022

There is no agreed definitive test for asthma, therefore, clinical diagnosis relies on a thorough health history, clinical findings, and assessment of symptoms with treatment. This patient’s history and physical examination fit the criteria for asthma and treatment in line with asthma management.

ACE

A chronic iatrogenic cough is widely recognised as an adverse effect of ACE inhibitors, which are prescribed as anti-hypertensives, or for heart failure. ACE inhibitors increase the sensitivity of the cough reflex in around 15 per cent of patients taking the medication. It typically presents as a persistent dry cough combined with a tickle in the throat.

A cough from ACE inhibitors can begin days, weeks, or months after starting the drug. The most effective treatment is to terminate the ACE inhibitor. Diagnosis is confirmed by the resolution of the cough usually within one-to-four weeks. This iatrogenic cough was easily ruled out as a cause of the chronic cough because the case study patient was not taking an ACE inhibitor.

GORD

Extrapulmonary conditions are also commonly associated with cough, including GORD.

GORD is a common presentation in primary care that occurs when the reflux of stomach contents causes symptoms and/or complications. A cough is a common symptom that occurs when acid infusion into the distal oesophagus increases both the frequency of coughing and cough reflex sensitivity. The non-specific symptoms of GORD, such as a cough, can be confused with pulmonary disease. Common symptoms can include a chronic cough, heartburn, dysphagia, acid regurgitation, chest pain, and hoarseness.

Diagnosis of GORD is considered in the absence of exposure to environmental irritants, smoking, no ACE inhibitor, asthma, and rhino-sinus disease, and with a normal CXR. Physical examination has no differentiating features, but patients may often be overweight or obese. Although not widely available in primary care, 24-hour oesophageal pH monitoring can confirm reflux disease-related cough.

Where GORD is considered a differential diagnosis for a chronic cough, a therapeutic trial of a proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) for eight weeks may be commenced. Alleviation of symptoms can take up to three months. PPIs are unlikely to be useful in improving cough symptoms unless patients have peptic symptoms or evidence of acid reflux.

PPIs remain the main treatment choice for GORD, but new evidence regarding the safety of long-term use has emerged. Treatment in patients diagnosed with GORD aims to relieve and control symptoms at the lowest dose for the shortest time, with re-evaluation for PPI complications in long-term use. This patient denied any typical GORD symptoms other than a cough, so it was ruled out.

Figure 2: Chronic cough care algorithm to guide and support clinical decision-making

UACS

UACS describes a variety of signs and symptoms previously referred to as post-nasal drip syndrome (PNDS), rhinitis, and rhinosinusitis. It typically presents with a chronic cough, frequent throat clearing, post-nasal drip, and blocked and runny nose. The physical exam includes respiratory, ear, nose, and throat. Findings may include post-nasal drip in the posterior nasopharynx, mucopurulent or mucoid sputum and secretions in the nasopharynx and oropharynx, and/or cobblestone appearance of the posterior oropharynx.

Treatment includes nasal corticosteroids, antihistamines, decongestants, and antibiotics for sinusitis.

UACS was considered as a differential diagnosis for the patient with chronic cough, but ruled out as clinical findings and symptoms did not fit with the characteristics of the disease.

Conclusion

A clinical history focused on cough characteristics and associated symptoms, combined with a physical examination, is a key part of the clinical decision-making process. A good history can provide important clues in making a differential diagnosis in patients who present with a chronic cough. Investigations such as CXR, spirometry, and peak flow, can be performed as part of a systematic approach to include and exclude common causes of chronic coughs.

This article outlined the pathological process and diagnostic modalities in four common causes of chronic cough in primary care. The use of an evidence-based decision-making pathway, which accompanies this narrative, guides the clinician to make an informed decision safely and confidently in diagnosing and treating a patient with a chronic cough who presents in primary care.

References

1. Chen SL, Hsu HY, Chang CF, Lin EC. An exploration of the correlates of nurse practitioners’ clinical decision-making abilities. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(7-8):1016-1024.

2. Kilpatrick K. Understanding acute care nurse practitioner communication and decision-making in healthcare teams. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(1-2):168-179.

3. Oxholm C, Christensen AS, Nielsen AS. The ethics of algorithms in healthcare. Camb Q Health Ethics. 2022;31(1):119-130.

4. Chung KF, McGarvey L, Song WJ, et al. Cough hypersensitivity and chronic cough. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022;8(1):45.

5. Kuzniar TJ. Assessment of chronic cough. BMJ Best Practice. 2023; UK: BMJ Publishing Group. Available at: www.bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/69.

6. De Vincentis A, Baldi F, Calderazzo M, et al. Chronic cough in adults: Recommendations from an Italian intersociety consensus. Ageing Clin Exp Res. 2022;34(7):1529-1550.

7. Morice AH, Millqvist E, Bieksiene K, et al. ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children [published correction appears in Eur Respir J. 2020 Nov 19;56(5):]. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(1):1901136.

8. Chung KF, Pavord ID. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and causes of chronic cough. Lancet. 2008;371(9621):1364-1374.

9. Gibson P, Wang G, McGarvey L, et al. Treatment of unexplained chronic cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(1):27-44.

10. Global Initiative for Asthma. Pocket guide for asthma management and prevention (for adults and children older than five years). 2022; GINA. Available at: www.ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/GINA-2022-Pocket-Guide-WMS.pdf.

11. Levy ML, Bacharier LB, Bateman E, et al. Key recommendations for primary care from the 2022 Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) update. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2023;33(1):7.

12. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Guidelines. Asthma: Diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management. London: NICE; 2021. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80.

13. Louis R, Satia I, Ojanguren I, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis of asthma in adults. Eur Respir J. 2022;2101585.

14. Shim JS, Song WJ, Morice AH. Drug-induced cough. Physiol Res. 2020;69(Suppl 1):S81-S92.

15. Barnes RA. Pneumonia and ACE inhibitors and cough. BMJ. 2012;345:e4566.

16. Kahrilas PJ, Altman KW, Chang AB, et al. Chronic cough due to gastroesophageal reflux in adults: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;150(6):1341-1360.

17. Katz PO, Dunbar KB, Schnoll-Sussman FH, Greer KB, Yadlapati R, Spechler SJ. ACG clinical guideline for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(1):27-56.

18. Freedberg DE, Kim LS, Yang YX. The risks and benefits of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: Expert review and best practice advice from the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):706-715.

19. Maret-Ouda J, Markar SR, Lagergren J. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: A review. JAMA. 2020;324(24):2536-2547.

20. Mathur A, Liu-Shiu-Cheong PSK, Currie GP. The management of chronic cough. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. 2019;112(9):651-656.

21. Bickley L, Szilagyi PG, Hoffman R. Bates’ guide to physical examination and history-taking. 13th edition. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2021.

22. Rajagopalan M. Assessment of clubbing. BMJ Best Practice. 2023. Available at: www.bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/623.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.