Can you remember what a calorie is? Let me see. My recollection is that it’s the energy required to raise the temperature of a litre of water by… er… um… a certain amount? So, clearly I had to check and it turns out that it’s the amount of energy needed to raise the temperature of 1g of water by 1ºC or, to be precise, 4.1868 joules. Well, I’m sure you’re glad we cleared that up.

The ‘calories in, calories out’ theory has been with us, in developing forms, since Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier built the first calorimeter shortly before losing his head – literally – during the French Revolution. The American physiologist Wilbur Atwater developed the modern concept in the closing years of the 19th Century, burning food to see how much energy it contains. Indeed, when using student volunteers in the course of his metabolic studies, he would set fire to their faeces. Where other scientists would have perhaps tried to find a way around this challenging and malodorous business, Atwater didn’t flinch. Although, I should add that I can’t find any reference to how he actually managed the incineration process.

His motivation was not about calorific restriction. Instead, he was concerned that the poor were not getting enough calories in their diet and he wanted to be able to make scientific recommendations to help improve their lot. Anyway, it’s a curious thought that ‘calories in, calories out’ is still the mantra well over a century after Atwater refined it. It underpins the ‘eat less, move more’ school of weight control thinking and has resulted in the dietary obsession that was kick-started by the US Senate in 1977 when it recommended a low fat, low cholesterol diet for all. The fat was, of course, replaced by sugar and salt and global obesity trebled between 1975 and 2016.

At this stage it is estimated that 1.9 billion people are overweight. It comes as no surprise that the incidence of type 2 diabetes has more than doubled over the past 40 years. Incidentally, the most obese country in the world, with 74.6 per cent of the population overweight, is American Samoa. The least obese is Vietnam with a shade over 2 per cent. The US weighs in at 36.2 per cent, the UK at 27.8 per cent, Ireland at 25.3 per cent, and food-loving France at 21 per cent.

It seems that chopping and cooking food makes calories more easily accessible during digestion

Of course, the demonisation of fat was an obsession of another American scientist, Ancel Keys, and the object of his so-called lipid hypothesis about which I’ve written here before. The process, however, was clandestinely encouraged by the US sugar industry and in 2016 a researcher at the University of California found the smoking gun.

Documents uncovered by Prof Stanton Glantz of UC San Francisco showed that in 1967 the Sugar Research Foundation, a sugar industry body now known as the Sugar Association, paid Harvard scientists to publish cherry-picked studies that minimised links between sugar consumption and heart disease, while pointing the finger at dietary fat. The publication that unleashed this on the world was no less than the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). The NEJM has required disclosure of financial assistance only since 1984.

“They were able to derail the discussion of sugar for decades,” Glantz told The New York Times.

None of the Harvard scientists are still alive, but one of them, David Mark Hegsted went on to be head of nutrition at the US Department of Agriculture where he drafted the 1977 government dietary guidelines.

It appears that the sugar lobby is still trying very hard to shape the narrative on diet. It was reported in 2015, again by The New York Times, that Coca-Cola had provided millions of dollars in funding to scientists who “sought to play down the link between sugar and obesity”. Shortly afterwards it was revealed that the US confectionery industry was funding research with an almost comical theme: To suggest that children who eat sweets weigh less than those who don’t. One is left wondering where they found a cohort of the latter, but never mind.

The Sugar Association, when questioned about the 1967 outrage, admitted that it should have been more transparent, but added that industry-funded research had shown that sugar does not have a unique role in heart disease. My emphasis. Speaking of diet and calories, I came across an interesting snippet the other day: It seems that chopping and cooking food makes calories more easily accessible during digestion. Richard Wrangham, a primatologist at – once again – Harvard, suggests that the evolution of humankind needed the development of cooking. I shall remember that when I’m next rattling the pans.

I also learned more about a subject I mentioned here before: Resistant starch. The theory is that, say bread or pasta, that has been cooked, cooled, and reheated (like toast or microwaved leftover tagliatelle) has its glycaemic index (GI) lowered. I now read that scientists in Sri Lanka have found that the GI of rice that is cooked, anointed with coconut oil, cooled and reheated is halved. I can’t find a reference to an in vivo study, but it’s encouraging for those of us who like an occasional carb fest.

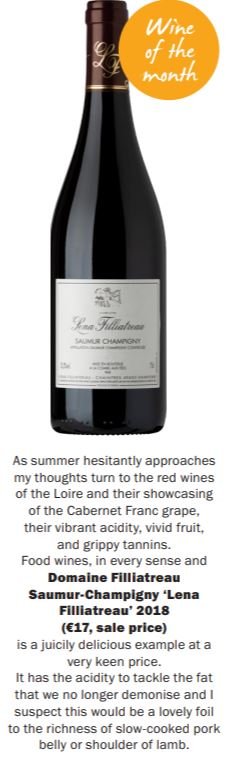

This puts me in mind of the joys of toasted sourdough with maybe some goose or pork rillettes and I have the perfect wine to accompany such an indulgence. It delivers a further bonus in having very, very little residual sugar. This is also an opportunity to remind readers that Whelehans Wines, in what used to be The Silver Tassie in Loughlinstown, is an oenophile’s dream.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.