Decades ago, during an idyllic camping trip to Finland and Norway, my wife and I lost a purse. At Tromsø Police Station a smiling officer transcribed our statement into Norwegian; I signed it… then he guffawed: “Hjör! Hjör! Hjör!” We stared at him. “You’ve just sold me your house!” he exclaimed. Our laughter erupted, mine tempered with relief that he was only joking. So, Prof Brendan Kelly’s citing of peer-reviewed studies showing that the Finns and Norwegians are among the five happiest nations in the world confirms my own experience.

But… the science of happiness? Conceding the subjective nature of happiness, Prof Kelly explains that his book “recruits the happiness science of the past few decades” to answer questions like “[i]s there a single set of guidelines, core principles or essential strategies that I can recommend to people who come to see me and apply in my own life so as to increase happiness, wellbeing, and satisfaction”? The author’s interest was also sharpened when in 2020, with his 47th birthday approaching, Prof Kelly learned of multiple worldwide studies reporting that “47 is the age of minimum wellbeing and maximum unhappiness on planet earth”. At least one reader, well past 47, is always reassured to hear Otis Clay’s, The Only Way is Up (1980).

Written in two parts, the first – ‘The Science of Happiness’ – considers ‘Who we are’, ‘What we do’, and the ‘Six principles of a happy life’; and the second – ‘Strategies for Happiness’ – offers reflections on sleep, dreaming, diet, movement, doing, social connections, and losing oneself.

Thus far, I have had a life blessed with good health and good luck. But an unsettling thought arose as I began to read: Might this book prompt uneasy comparisons of my own life with Prof Kelly’s happiness-related principles and strategies, raising uncomfortable questions? The answer, I am pleased to say, was yes. This well-written, thought-provoking, and entertaining exploration of happiness-related research, afforded opportunities to examine my flaws, provided insights into their nature, and suggested possible means of amelioration. To take two (of many) examples; first, the role and relevance of dreams had passed me by (no; I had ignored them), and I shall follow up interesting evidence supporting Prof Kelly’s comment that “[w]e do not dream enough and we do not sufficiently value our dreams”. Second, the merit of social connections outlined by the author chimes with my wife’s view that I could benefit from relationships not only with books, but with other people. Both he and she are right. Further, the ‘Connecting in the time of Covid-19’ section offers a timely perspective on human bonding.

I heartily agree with Kelly’s highlighting of the value of sleep (our bedtime is typically around 21.30), cats, gratitude, and other contributory factors to happiness. So too, losing oneself; but whereas the author got enjoyably lost in night-time St Petersburg, I achieved it in broad daylight in what was then Leningrad, intrigued at the diverse ways in which tins of Soviet provender could be stacked in the windows of department stores. I largely share Kelly’s views on exercise, and I guess he too would endorse Rebecca Solnit’s view in Wanderlust: A History of Walking (2000) that walking is a state in which mind, body, and the world “are aligned, as though they were three characters finally in conversation together, three notes suddenly making a chord”.

But even writing this while nursing an inflamed Achilles tendon, I maintain that my decades-long love of long-distance cross-country running has brought me much happiness, though admitting that immoderate bouts of strenuous activity don’t necessarily confer favours on one’s physiology. And even as I mounted my dietary high horse to demur at some of the author’s views, I was pleased with his welcome assertion that “[o]ther neglected nutrients that can help boost mental wellbeing include iodine, magnesium, and – of all things – cholesterol”, adding that dietary cholesterol “is necessary for brain health”.

In presenting a science of happiness, Prof Kelly’s thoughts on meditation, mindfulness, and belief necessarily approach a boundary with philosophy, a discipline that he is clearly comfortable with. So, is happiness necessary for a well-lived life? For example, we have this Shavian assertion in Man and Superman (1903): “A lifetime of happiness! No man alive could bear it: It would be hell on earth.” And might happiness, if uninterrupted, confer an immunity to failure, denying opportunities to learn from our mistakes?

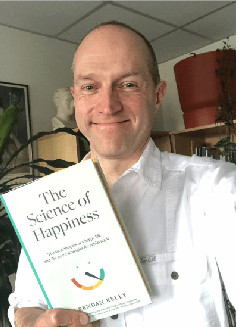

Prof Brendan Kelly

In her Ideals and Illusions (1941), philosopher Susan Stebbing contemplates “the pursuit of happiness” as voiced in the American Declaration of Independence (1776). She suggests that although the ideal was fine as a principle, it had not been translated into practice, citing Clive Bell’s view that all civilisations have stood on inequality. As a result, Stebbing considers that “it was unquestioningly taken for granted that the sort of happiness appropriate to the one must for ever remain out of the reach of the other”.

My understanding of what it means to be alive is enriched by The Science of Happiness, and Prof Kelly must now order a supply of his favoured chocolate brownies and begin work on The Philosophy of Happiness.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.