“I have not yet levitated but that, surely, is entirely reasonable.”

For some, learning to meditate seems like an esoteric activity laden with 1960s counter culture overtones. But meditation has become an interest of a growing number of people. Yet with all this talk of mindfulness, most of us unenlightened mere mortals have some questions.

What is meditation, at what point will I have to start dressing like Mahatma Gandhi, and more importantly, will I genuinely be able to levitate if I try hard enough because this whole dealing with gravity stuff is starting to get tiring?

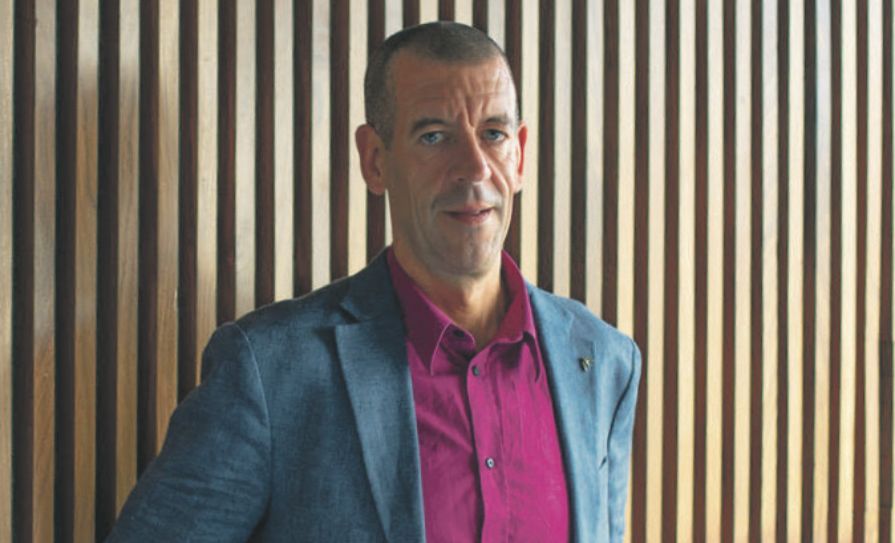

The answer to some of these questions and many others is what Prof Brendan Kelly, Professor of Psychiatry at Trinity College Dublin attempts to answer in his new book The Doctor Who Sat for a Year as he chronicles his year-long journey of daily meditation.

Anchored around the central framework of Buddhism’s four noble truths and the noble eightfold path, this year-long expedition takes us from the foundational truth that life is suffering, or more specifically unsatisfactoriness, to what nirvana, the ultimate achievement of meditation might look like.

While the origins of meditation are largely grounded in the teachings of Buddhism, the book reflects on an assortment of source materials ranging from stoicism to sufism, in an effort to understand what can be learned from a daily meditation practice.

For me the book highlights several fundamental learning points. The first being that most of our suffering in life, or the negatively valenced emotions we experience are based on a focus on either past or future, rather than the present moment. This is best described by the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu. “If you are depressed you are living in the past. If you are anxious you are living in the future.” The purpose of meditation then becomes an exercise in focusing on the present and insulating oneself from the endless buffeting of concerns related to past and future, albeit temporarily so.

Importantly, the practice of meditation is the short period of reflective contemplation, while mindfulness is the act of taking what one has learned and applying it to the rest of one’s life. The purpose of meditation then is not meditation in and of itself; and the brief cessation of mind-wandering that can be achieved. It is added value in taking what one has learned out into the world and not hiding in such reflective states as illustrated by Thoreau when he “went to the woods to live deliberately”. He also “left the woods for as good a reason as I went there”.

The second key learning point illuminates the concept that so much of what we suffer in life is how we respond to the events in life rather than the events themselves. This message is deeply rooted in the Buddhist philosophy that: “Pain is inevitable, suffering is optional.” This is not to suggest we do not experience real pain in our lives, but that we ‘suffer’ far more than we need to. We are reminded to reflect on the stoic musings of Marcus Aurelius when he says: “You have power over your mind – not outside events. Realise this and you will find strength.”

A key figure that features throughout the book is Trixie, the author’s cat. Much time is spent pondering whether Trixie has achieved transcendence and lives entirely in the present or has no idea why her owner sits for prolonged periods with his eyes closed and is thereby very unlikely to feed her cheese.

Woven throughout the book are stories of the suffering of psychiatric patients as illustrations of how we struggle so much in our own minds and occasional glimpses into the, at times sordid past of psychiatry in Ireland.

Having mediated each day for a year, the primary take away for me is not that a daily meditation practice inevitably leads to some glorious endpoint, but that it serves as a looking glass on the simple and strange ways we all spend moments of our lives.

As Annie Dillard points out “How we spend our days, is of course, how we spend our lives.”

To me this is the revelation of meditation, and I believe that of the author, that we need to focus less on the grander moments that puncture our existence, but the tiny fragments that make up each of our days.

The Doctor who Sat for a Year by Prof Kelly is a wonderful example of how we can all work towards doing that.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.