Trauma is everywhere. More precisely, the term “trauma” is now used to describe everything from truly traumatic experiences that would disturb most people, to the routine ups and downs of everyday life that leave some of us slightly upset. Everything is traumatic, it seems.

It is not entirely clear when this trend started, or why there was a collective, unconscious decision to expand the idea of trauma to this point. What is clear is that the word “trauma” has lost much of its meaning, with the result that the suffering of people who experience deep trauma is being systematically devalued.

The subjective impact of life events varies between individuals. Not everyone is traumatised, even when terrible things happen. Some people are fine. The fact that someone does not describe trauma in their past does not mean that they are repressing something dreadful. It probably means that they did not experience traumatic events. They are not traumatised, repressed, or governed by unacknowledged psychological wounds. They are fine.

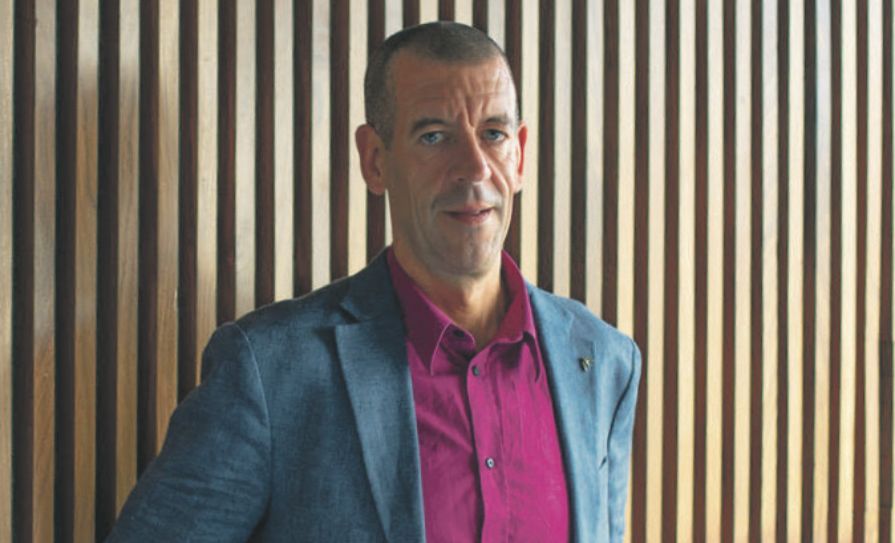

Against this background, I approached Dr Chris Luke’s memoir, A Life in Trauma, with some trepidation. My anxiety was quickly dispelled, however, not least by the book’s subtitle: Memoirs of an Emergency Physician. If anyone is routinely exposed to high levels of trauma, both physical and psychological, it is an emergency physician.

The other reason why this book raised slight anxiety in me is because it awakened my memories of working in emergency medicine many years ago. As a surgical intern, I was first on-call to an emergency department one night in every four (I think) and every fourth weekend. It is in everyone’s interest that I do not linger on that period of my life. Let’s just say that the contrast with Dr Chris Luke’s work in this field could not be starker.

From the outset of Luke’s memoir, it is apparent that he has a genuine gift and deep passion for emergency medicine. (I had neither.) Luke’s commitment is inspiring and this account of his professional career invigorates me to engage

more deeply in my chosen field (which, thankfully, is not emergency medicine).

But this is a book about good medicine in the broadest sense, moving beyond the clinic and into service development. Most readers will be familiar with Luke’s advocacy on the airwaves and elsewhere, arguing for better, smarter services that truly meet the population’s needs. All of that is in here.

I will not rehearse every twist and turn in Luke’s story because he does this far better in the book than I can in a review.In a nutshell, Luke qualified at UCD in 1982 and has worked as an emergency physician for over 35 years. He worked in Ireland, the UK, and Australia, and has been a consultant in emergency medicine in Cork for more than 20 years.

With this trajectory, exposure to trauma is inevitable. Much of this is discussed in the book in a way that is engaging, direct, honest, and utterly human.

Luke tells a complicated, compelling story. As with any life, no single event, no matter how dramatic, can be seen

in isolation. Everything has a context. Most lives contain infinitely more good judgements than poor ones, more steps

than missteps. Luke’s story is no different: It is the totality that matters, vastly more than any single event.

For me, two points emerge clearly. The first is the potential for a committed clinician to make a difference. Medicine can be dispiriting at times, as outcomes appear to be shaped by forces beyond the clinician’s control: Poverty, trauma, service deficiencies, random bad luck, and a host of other things. Luke’s account gives plenty of reason for hope: The individual clinician can make a genuine impact, even in the face of these overarching factors.

The second point is that delivering healthcare is ultimately about people helping people. Luke’s acknowledgements list is vast, recognising colleagues, friends, and family who have contributed to his story. I was especially moved by Luke’s account of his visits to psychiatrist Prof Anthony Clare in 2007, just months before Clare’s untimely death. Clare was “profoundly sympathetic” to Luke’s difficulties. When Clare died suddenly later that year, Luke felt “grief-stricken, as if I’d lost a recently discovered, highly charismatic uncle”.

Like Clare, Luke has a keen appreciation of the challenges of medicine, the value of collegiality, and the essential humanity that lies at the heart of both. How Luke developed this understanding makes for an engrossing, invigorating read.

Prof Brendan Kelly is Professor of Psychiatry at Trinity College Dublin and author of The Science of Happiness: The Six Principles of a Happy Life and the Seven Strategies For Achieving It (Gill Books).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.