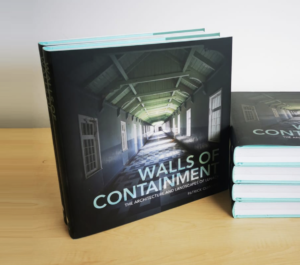

TITLE: Walls of Containment: The Architecture and Landscapes of Lunacy

AUTHOR: Patrick Quinlan

PUBLISHER: University College Dublin Press

REVIEWER: Prof Brendan Kelly

Institutions feature heavily in the history of psychiatry in Ireland. While this was also the case in other countries, Ireland’s “mental hospitals” were especially large by international standards for much of the 19th and early 20th Centuries. When the institutions were finally dismantled, Ireland’s shift to community care was also relatively slow compared to other countries. Although significant progress was eventually made, more still needs to be done, even today, to improve community care.

From an historical perspective, the mid-1700s saw the first signs of change for people with mental illness in Ireland. St Patrick’s Hospital was founded in 1746 following the benevolent bequest of Jonathan Swift (1667-1745), satirist, writer, and Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral. St Patrick’s was a private, charitable institution, aimed at caring for a finite number of people, without the broader, population-level responsibilities of government institutions. While the initiative was an important, groundbreaking one, more was needed.

In Cork, Dr William Hallaran founded a public asylum in 1791, to accommodate 24 patients. By 1822, Cork Lunatic Asylum had expanded to cater for over 300 people. The remainder of the 19th Century saw the construction of a vast network of public “mental hospitals” across Ireland, reflecting well-intentioned efforts to look after the destitute mentally-ill during times of poverty, uncertainty, and even famine.

Regrettably, the asylums were tragically underpinned by a cast-iron belief that institutionalisation was intrinsically therapeutic. In 1858, the Commissioners of Inquiry into the State of the Lunatic Asylums wrote that “it is of the utmost importance that cases of insanity should as speedily as possible be removed to an asylum”. This position ref lected both public and professional beliefs at the time and fuelled enthusiasm for the new “mental hospitals”.

As a result of this approach, the institutions continued to grow throughout the 19th and early 20th Centuries, before going into decline from the 1970s onwards. Notwithstanding the shift to community care since then, many of these buildings still stand. Some remain in use as healthcare facilities. Others have moved to private ownership. Others are essentially derelict.

It is beautifully produced, so great credit goes to University College Dublin Press for creating such an inviting, impactful volume

The histories of these institutions have not received the attention that they merit. There have been dedicated accounts of certain, specific hospitals including St Patrick’s, St Brendan’s (Grangegorman), St Vincent’s (Fairview), Bloomfield (Dublin), Our Lady’s (Cork), and Holywell (Belfast), among others. But the overall history of our “mental hospitals” and, specifically, the histories of the buildings themselves have awaited detailed examination for some years now. In an era when historical institutions of various sorts are increasingly scrutinised, the history of our psychiatric institutions deserves far more attention than it has received to date.

This gap in the historical literature is ably addressed in a new book by Patrick Quinlan, published by University College Dublin Press and titled Walls of Containment: The Architecture and Landscapes of Lunacy. This magnificent book addresses this complex, multi-layered history in a detailed, nuanced fashion. It is beautifully produced, so great credit goes to University College Dublin Press for creating such an inviting, impactful volume. The story it tells deserves nothing less.

The book itself includes not just a detailed text, but also more than 400 historic and contemporary photographs, drawings, and diagrams. The photographs of the old hospitals, many by David Killeen, are very affecting. These images show hospital wards, buildings, and outhouses in varying states of abandonment and neglect, palpably echoing the ghosts of their institutional pasts. The photographs are complemented by images of plans and maps that further evoke the scale and atmosphere of the institutions. The book also presents a detailed gazetteer that explores the history of 29 former asylum sites on the island of Ireland. The information here is exceptionally valuable in describing these campuses and locating them within the broader story of Ireland’s institutional past.

Patrick Quinlan is very well placed to write this book. He is a practising architect who holds a Masters in Urban and Building Conservation from University College Dublin. He has professional experience spanning from modern healthcare to the conservation and reuse of a variety of historic structures. He is a past recipient of the international Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Dissertation Commendation and is currently undertaking a PhD at Birkbeck, University of London, focused on the contested legacies of Ireland’s former asylum sites.

Quinlan’s wonderful book will undoubtedly become the vade mecum for the history of Ireland’s “mental hospital” buildings and, as such, adds significantly to the broader historiography of psychiatry in Ireland. The text is at its strongest when it focuses on the architecture of the hospitals and the history of that architecture. The images are at their strongest when they juxtapose the past with the present, and thereby demonstrate the richness of the history they document.

All told, this is an extraordinary book. Inevitably, the enormity of the programme of institutionalisation that it depicts raises profound questions about Ireland’s institutional past, our attitude towards people with mental illness, and the future of the old “mental hospital” buildings themselves. There are no simple answers to these questions, but this book’s vivid demonstration of past excesses makes an important contribution to understanding the issues.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.