Covid-19 is one of the greatest challenges the World Health Organisation has faced since its foundation in 1948. More than six months since the declaration of a public health emergency, David Lynch looks at its performance so far and its future role

On the final day of last year, Chinese health officials contacted the World Health Organisation (WHO) to inform it about clusters of over 40 patients with pneumonia of unknown cause, detected in Wuhan city.

The rest, of course, is a history that we have all been living through.

On its website, the WHO describes its lofty mission to work “worldwide to promote health, keep the world safe, and serve the vulnerable”. It has certainly been at the very centre of the Covid-19 pandemic response.

The WHO’s Director General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Covid-19 Technical Lead Dr Maria Van Kerkhove, and Ireland’s own Dr Michael Ryan, Executive Director, Health Emergencies Programme, quickly became familiar faces with their regular televised media briefings during the early months of the pandemic.

It was at these press briefings that the WHO Director General declared the novel coronavirus outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) in late January. In early March, he officially characterised the situation as a “pandemic”.

There has been praise for the work of the Organisation over the last six months from many working in global health. However, charges of inefficiency, lack of transparency and politicisation have been raised by others. Issues ranging from the WHO’s relationship with the Chinese government, to its messaging about virus transmission, have prompted critical commentary.

Of course, the most vocal of all WHO critics has been US President Donald Trump, who has accused the Organisation of being slow to inform the world of the pandemic and being too close to the Chinese government.

While it may be easy to dismiss the pronouncements from the Oval Office as politically motivated, other more nuanced critiques have also emerged from public health circles. For instance, after last month’s confusing WHO statements on asymptomatic individuals, The Guardian carried a headline declaring ‘WHO expert backtracks after saying asymptomatic transmission “very rare”’.

“Modelling studies estimate that up to 40 per cent of coronavirus infections could be transmitted by people who have the virus but no symptoms, a WHO expert has acknowledged after her comment on Monday that asymptomatic transmission was ‘very rare’ caused a stir,” reported The Guardian on 9 June.

The original comments and subsequent high-profile clarification by Dr Van Kerkhove were widely criticised, with some public health experts emphasising that consistent and clear messaging is one of the WHO’s most important functions during the present pandemic.

Irish view

Irish doctors who have commented online regarding the WHO’s performance have often been supportive of its work (see panel), sometimes declaring national pride at the high-profile role played by Dr Ryan, who completed his medical training at NUI Galway and received a Masters in Public Health at University College Dublin (the WHO told this newspaper that Dr Ryan was not available at this time for interview).

But this relationship between Irish healthcare and the WHO goes well beyond mere declarations.

The Department of Health told the Medical Independent (MI) it has worked especially closely with the WHO during the pandemic and that the Irish State has provided financial support to the global response directed by the Organisation.

“Ireland has a longstanding relationship of close co-operation with WHO in Ireland, Geneva and across the world,” a Department of Health spokesperson told MI.

“In addition to our regular interactions and participation in the WHO governing body meetings at both technical and political levels, the Covid-19 pandemic has naturally necessitated an intensification of our engagement and communications with WHO.”

This intensive engagement “has taken place on a regular basis across all levels, from political decision-makers to technical experts, both as part of regular WHO engagement with all member states, the EU, and in a bilateral context”.

In stark contrast to the US President, who in April announced a halt to US funding to the WHO, the Department spokesperson said the Irish Government is “very supportive of WHO’s leadership role in co-ordinating the global response to Covid-19”.

The Irish State has provided €9.5 million in funding for WHO in 2020, a figure which marks a significant increase on last year.

“This funding is a combination of mandatory and voluntary contributions, which represents a four-fold increase on our contributions for 2019,” the Department spokesperson told MI.

“This is intended to support the regular operations of WHO, as well as its work in global co-ordination and in assisting more vulnerable and at-risk countries to adequately prepare and respond to the pandemic. “WHO and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) have also produced an extensive range of strategic and technical guidance for all member states to draw upon, which has informed Ireland’s public health measures and guidance.”

Although this current crisis is global in scale, over the past decade the WHO has been on the frontline during serious epidemics such as SARS, Zika and Ebola. Its performance during each, particularly with Ebola in West Africa 2014, sparked mixed reviews, with some even calling for its dissolution and the creation of a new global health agency.

‘WHO’s to blame?’

Associate Professor Adam Kamradt-Scott (PhD) is a specialist in global health security and international relations at the University of Sydney in Australia. He is the author of Managing Global Health Security: The World Health Organisation and Disease Outbreak Control (Palgrave Macmillan (2015) and in 2014, he wrote the article ‘WHO’s to blame? The World Health Organisation and the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa’ in the academic journal Third World Quarterly.

“The WHO has performed well under the constraints the Organisation currently faces,” Dr Kamradt-Scott told MI when assessing its role during the present pandemic.

“There have been mis-steps, such as the Director General’s language in describing the Chinese government’s behaviour, which has since been shown to be problematic.

“But the Organisation has followed the rules that its member states set down in 2005 in rapidly alerting the international community to the presence of a novel coronavirus.

“It enacted the International Health Regulations (2005) to convene an emergency committee, which concluded the criteria for a public health emergency of international concern were met on 30 January, and since that time the WHO has been providing regular updates, guidance and technical assistance to its member states.

“So yes, it has performed well under the current system.”

Regarding what the Organisation could improve upon in its response in the coming months, Dr Kamradt-Scott said it would benefit from a reassessment of staffing policy and should increase non-medical expertise.

“My personal and long-standing view is that the WHO will be strengthened when it broadens its employment conditions to include more non-medical employees,” he told this newspaper.

“Medicine does not prepare you for dealing with the political realities of global health. And as much as doctors often like to think of themselves as being able to write good health policy, the fact is that it requires multiple contributions from a wide array of expertise — from nursing, to allied health, to economists and political scientists.

“The WHO recognised the benefit of including anthropologists in the health emergency response in 2014 during the West African Ebola outbreak, but the WHO’s understanding of the social sciences has not moved beyond anthropology in the six years since.

“The international community deserves a multilateral health agency that brings together health expertise from across multiple sectors to inform future emergency response.”

Despite its flaws, Dr Kamradt-Scott said the WHO is “critical” to the Covid-19 challenge.

“The simple fact is that we live in a highly interconnected world, and in that context, the role of the WHO is critical to the current pandemic,” he said.

“This crisis is not limited to one country or even one region of the world. It is global. For that reason alone, we need an organisation that has the ability to help try and co-ordinate an international response.

“[An organisation] that has the ability to reach across borders to gather together the best possible expertise to advise and assist governments, and hopefully, in the event a vaccine is successfully developed, to ensure it is a global public good that is made freely accessible to everyone, irrespective of their ability to pay.”

The WHO was established by constitution in April 1948 and its reach has grown significantly in the decades since. It currently has 194 member states, across six regions, and from more than 150 offices.

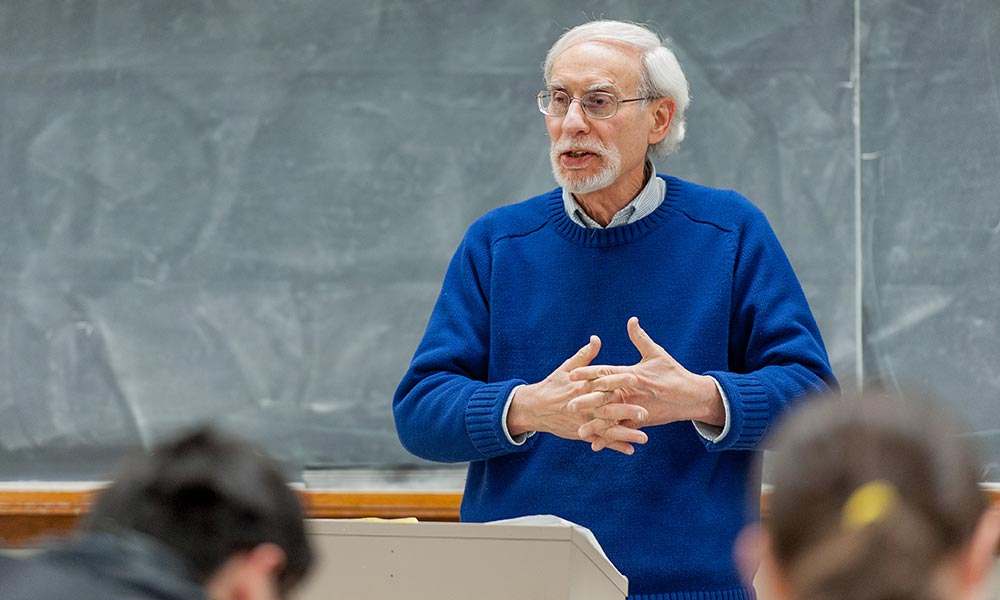

Prof Theodore M Brown, Professor Emeritus of Medical Humanities at the University of Rochester, New York, US, is the co-author of the recently-published The World Health Organisation — A History (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

He told MI that before looking at the question of the WHO’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic, observers must take into account that “by international law as inscribed in the International Health Regulations of 2005, the WHO has limited powers and must rely on the co-operation of member states to supply epidemiological information and to adhere to recommended public health actions based on that data”.

‘Essential’

Prof Brown contrasted the power and reach of the WHO with some other international bodies to which it is often compared.

“Unlike the WTO [the World Trade Organisation], the WHO has no enforcement power or sanction authority and must resort instead to delicate international health diplomacy if it is to provide leadership during a global health crisis such as the one we’re in.”

On the positive aspects of the WHO’s response to the pandemic, Prof Brown said the “WHO has done a credible job of maintaining a flow of outbreak information and communicating”.

“And it has assembled teams of respected experts to assess it objectively and to provide credible recommendations about best-case public health responses to the spread of Covid-19.”

In terms of where the Organisation may have fallen short, Prof Brown said “the WHO needs adequate resources and the co-operation of member countries to do its best work.”

“If either is lacking, WHO is hamstrung, so the real focus should be on getting countries to contribute adequately and to collaborate authentically and fully.”

Prof Brown said the WHO remained vital in the face of the current crisis, and if it didn’t exist, the world health community would have to create it.

“[The] WHO is essential,” he said. “If it didn’t exist, it would be beholden on the world community to create an international agency with its stipulated functions and to empower it to do its job.”

The local view of the global response

The Department of Health said the strategic and technical guidance provided by the WHO since January “has informed Ireland’s public health measures and guidance” in response to Covid-19.

Irish doctors contacted by this newspaper also emphasised the importance of the WHO.

Prof Joe Barry, Professor of Public Health Medicine at Trinity College Dublin, told MI that “the WHO has taken a global view, while customising its communications, depending on the region in question”.

“Consistent, clear communication of public health principles, advice and actions has been a feature and there has been an emphasis on the importance of preventive behaviours that are implementable at the level of the individual.

“Its Covid-19 Health System Response Monitor can facilitate international comparisons of responses to the pandemic.”

What could the WHO improve in its response? “More effort could be put into addressing guidance differences between the WHO and the ECDC,” said Prof Barry.

But he added that “the WHO plays a vital role in pandemics because it can facilitate learning across countries and regions and can act as an early identifier of travel-based transmission and outbreaks”.

“Many of the guidance documents used by Irish doctors working on the frontline of Covid-19 have their origins in the WHO.”

Prof Samuel McConkey, Associate Professor and Head of the Department of International Health and Tropical Medicine, RCSI, told MI that the WHO is “essential for this [Covid-19] and for future pandemics”.

Looking back over the last six months, Prof McConkey praised much of the work that the Organisation had done since the onset of the crisis.

“They have provided accessible, wise advice from the Director General Dr Tedros Gebrejesus, Dr Mike Ryan, and David Nabarro, who have made themselves available to global and Irish media to give wise advice, at a time when many other leaders were lost, muddled and silent,” said Prof McConkey.

He believed the WHO leadership had spoken “truth to power” and that they “have advocated for help from resource-rich countries for resource-poor countries”.

“They have [also] advocated for a multilateral, internationally-co-ordinated approach to this problem, rather than the ourselves-alone, parochial and nationalistic one chosen by some countries.”

In terms of the lacking aspects of the international response and the areas the WHO may have to improve upon, Prof McConkey said it is too close to the start of this global health emergency for people to be drawing conclusions. However, he said increased preparation for future pandemics is needed.

“We are just at the beginning of this Covid-19 problem, so it is too early to say,” he said.

“The WHO and all of us need to put much more effort into preparing for pandemics in the future.

“For example, [to] have national and regional contingency plans in place, tested, drilled, and ready to execute at short notice, including prompt joint multilateral international actions, communications, data collections and sharing, and a repertoire of possibly effective responses.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.