An initiative by the ICGP is helping to ease pressure on over-worked GPs in rural areas and is continuing to grow. Niamh Cahill reports

Longer waiting times for a GP appointment, an inability to take on new patients, and the loss of GPs in rural areas have all become more commonplace in recent times.

An older and growing population, an ageing and depleting GP workforce, and expansions in the provision of ‘free’ GP care have placed huge pressure on general practice.

While the challenges are both onerous and numerous, various initiatives are underway to address the situation. For example, the International Medical Graduates (IMG) Rural GP Programme, developed by the ICGP, has proven a success since its recent establishment.

To date, the programme has attracted around 100 doctors from across the globe to small towns and villages. By the end of 2024 it hopes to have brought 250 experienced doctors to Ireland.

Doctors from South Africa, Canada, Sudan, Nigeria, India, and the Middle East, are currently practising through the two-year programme under the supervision of established GPs.

According to these established GPs, the international doctors have breathed new life into rural, isolated communities that would have faced the prospect of having no GP in the near future.

Background

While a shortage of GPs is a national issue, it has been a particular problem in rural areas for many years.

As time elapsed and official inaction persisted, it became apparent to many that increased training numbers alone would not be enough to bridge the gap.

This problem occupied the mind of Dr Velma Harkins, an experienced GP who has held many senior roles with the ICGP.

Based in Banagher, Co Offaly, Dr Harkins became increasingly concerned about the situation and believed a solution was urgently needed to ensure patients could access GPs locally.

She ran the local out-of-hours (OOH) GP co-op before the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and saw there the difficulties faced in getting doctors to cover overnight shifts.

“Everybody was worried about manpower and how we would support GPs in the future,” she told the Medical Independent (MI).

“The workload in general practice was increasing. If there aren’t enough GPs, how do you ensure quality and safety for patients? It didn’t require huge intellectual input to figure out that we needed to do something,” she recalled.

At the co-op where she worked, there were many international medical graduates. Dr Harkins became aware of the difficulties they faced in getting onto the specialist register in Ireland.

“Previously you could have some of these doctors working with a practice, but when the GMS GP retired they were unable to go for the list for that practice,” she explained.

“I thought if we can create a situation where doctors can be mentored and supervised in practices for a few years, and then afford them access to educational resources at the end of that time, they could get specialist registration with the IMC [Irish Medical Council] and make their lives in Ireland and take up

GMS positions.”

Dr Harkins was keen to not only help address GP shortages, but to provide supports and a career pathway for international medical graduates to encourage them to stay in Ireland.

Her idea became a reality in 2019 when an IMG pilot was launched. However, the outbreak of Covid-19 delayed the programme for two years.

It was reinitiated in 2022 with “bigger numbers and bigger practice involvement”.

The HSE provided financial support to help develop the programme and a programme manager and staff were hired.

“It’s been very exciting and we’ve learned so much,” said Dr Harkins.

“The people that are coming into the programme are amazing; their stories are amazing. That’s what has blown us away. You’re in awe of them.

“We’re very lucky to have people of this calibre coming into Ireland. This has been really joyful. Many of our colleagues were at the end of their tether and facing a brick wall, not being able to continue, and to get this new lease of life into the practice, somebody working with them, has been transformative. It’s a joy.”

Some of the doctors have come to Dr Harkins’ own practice. “Without them we would have struggled to get anybody in,” she admitted.

For practices in rural areas facing the prospect of having no GP, this has given them a new impetus, she said.

“It is making a huge difference in areas, especially in the south and mid-west.”

Criteria

All doctors applying must be eligible for the general register, which means they must meet English language requirements and other standards.

They apply to the programme via a detailed application form and must meet certain criteria. For example, they must have at least three years’ experience in general practice and completed hospital jobs in paediatrics and general medicine.

If the application is acceptable, a detailed interview takes place, after which time candidates are selected.

Following this process, doctors undergo a three-day induction programme and complete a detailed skills document. The doctors are provided with educational resources for self-directed learning, and are assisted to undertake the MICGP examination, leading to specialist registration with the Medical Council.

They work in routine daytime rural GP practice, as well as some OOH work. The fully established programme began in 2023 with 79 doctors. In April 2024, a further 16 doctors were due to commence the programme.

At home

Great care is taken to place candidates at a practice that best suits them and their families’ needs, according to Dr Harkins.

“We find they are moving lock, stock, and barrel. They are moving their families. That’s why it’s important we get the right place for them…. It’s a real commitment for them. The programme is challenging and we ask a lot of them. They want a better life for their families and children. Their commitment is to Ireland,” she said.

“Some of the doctors are very experienced GPs and have worked in Ireland before, but there are others who are new to the country. Increasingly, that’s who you want to attract, as you want people to come to Ireland as a first-choice destination. For these people, at the initial stage, there is a lot of time and input required by practices for the first three months.”

The ideal scenario, she said, would be if the doctors took up GMS lists here and stayed long-term.

“But even if they stay for five or 10 years there is a bonus. What we’re finding is that a lot of them will stay because the kids get settled in school after a few years here. Now they have an opportunity to stay as they are eligible for a GMS list. If they are in a practice, they can take over a practice or go on to partnership. They have real career opportunities.”

Still in its infancy, the two-year programme has so far proved to be very successful. But Dr Harkins is keen to build on this success.

“It’s very early days and we’ve been successful so far in attracting people. But we need to get word out about the scheme; that is a challenge.”

“There is no other country at the moment offering something like this. I’m quite sure that will change quickly and you will have other countries, like the UK, who has a crisis; they will find a mechanism to bring people in. The nice thing about Ireland is we’re small, and small numbers make a big difference in rural areas. We don’t need thousands of doctors to make a big difference; we

need hundreds.”

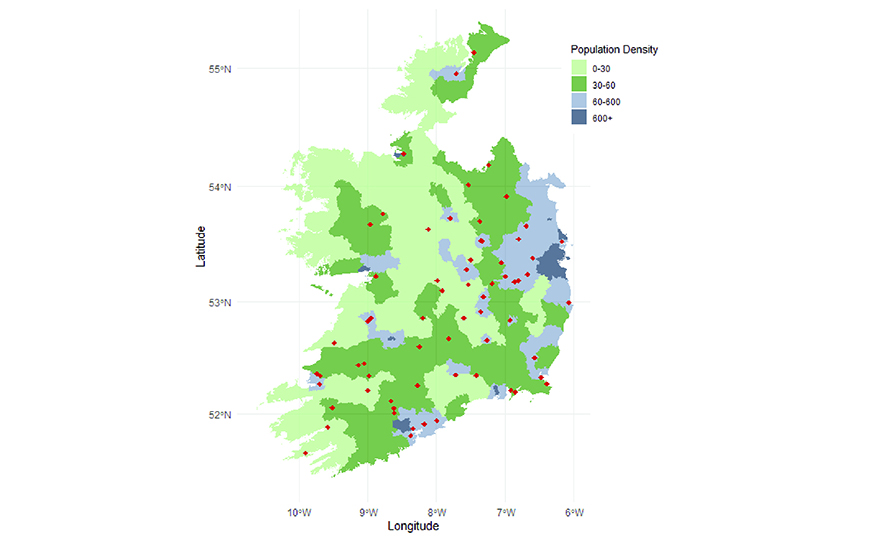

GP shortages exist everywhere, but the most acute shortages in recent years have been in rural areas, such as the Iveragh Peninsula in Co Kerry.

The region has a population of 8,000 people, but currently only has two GPs and another locum GP.

According to Dr Harkins, GP shortages are the “defining issue for general practice at the moment”.

“In rural areas, where GPs are ageing, now you have the possibility of continuity in that area where patients will have a GP. The doctors are settling in well and they seem to be enjoying it.”

Workforce deficit

ICGP Medical Director Dr Diarmuid Quinlan, who works with the programme, told MI that training more GPs in Ireland alone will not be sufficient because of the huge workforce deficit.

“We cannot train our way out of this workforce deficit,” Dr Quinlan explained.

“It’s too late.”

The Cork GP has called for a substantial and sustained investment in general practice. He provided an overview of healthcare statistics that present a concerning future unless action is taken.

Between 2019 and 2022 the hospital doctor workforce in Ireland rose by 23 per cent, from 9,700 to over 11,900. Dr Quinlan welcomed this expansion, but said in stark contrast the GP workforce is static. In the UK, the GP workforce is declining.

“In the UK, in a four-year period until November last year, the GP workforce dropped by 2.3 per cent and the population there is expanding. This is part of a global trend.”

“Our GP workforce is static. Our population is growing; we’re now at 5.1 million. The number of older people aged 65 and over has gone up 15 per cent. In 2019 it was 700,000, now it’s over 800,000. Older people consume vast amounts of healthcare, the majority of which is

provided in primary care. That’s a big uplift in older people and that will

keep accelerating.

“On average, [in] people aged 45-to-64, one-third have two diseases, mostly heart and lung [related]. But those aged 65-to-84 have three or more diseases and people aged 85 and over have four or more diseases.”

Currently, 14 per cent or around 600 GPs are over 65 and many will retire by the end of 2025.

There are 4,200 GPs nationwide. However, before the outbreak of Covid-19, the Department of Health and HSE stated that 6,500 were required.

Dr Quinlan said an increase in workload due to the pandemic, a growing ageing population, and GMS expansions have all placed further pressure on GPs. Shortages of GPs, particularly in rural areas, have become more frequent.

Support

For Dr Harkins, a significant component of the scheme is ensuring equity, where doctors are treated fairly and in a supportive manner.

It is also heavily focused on providing the best quality care to patients, she said.

“It’s all about the patient having high-quality care and this is a way of ensuring that is maintained. It suits everyone. It suits GPs here, it suits doctors coming in, and ensures patients will have a doctor where in two or three years there might have been nobody. This will future-proof some rural areas.”

Dr Harkins said the calibre of GPs on the IMG programme is “extraordinary”.

“There is a real depth of character there and resilience. The multiculturalism is great. We have a multicultural society. Irish society is no longer homogenous. Having doctors from many backgrounds is very healthy.

“One of the big pluses is that many of our doctors trained in Eastern Europe and can speak Russian and many languages.”

On the ground – Perspectives from two GPs on the IMG Programme

Dr Sara Malik

The North African country of Sudan is more than 5,000 kilometres from Ireland. Despite the distance, Sudanese native Dr Sara Malik says she does not feel like an outsider here. “I don’t feel foreign in Midleton,” she told the Medical Independent (MI).

The mother-of-two moved to Ireland in 2018 after completing the RCSI Master’s degree in medical education in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – a collaboration between the RCSI and a university in Dubai.

Before this, she studied and qualified in general practice under the UK MRCGP international programme, which allows doctors living outside the UK to become an international member of the Royal College of GPs.

While this enabled Dr Malik to practise as a specialist family physician, it did not provide her with the qualifications required to practise as a GP in the UK or Ireland.

Prof Ciarán O’Boyle was Director of the Master’s programme under which she studied. It was this connection that eventually motivated Dr Malik’s move to Ireland.

“I was really impressed with the standard of teaching provided,” she said.

“We had lecturers who flew from Dublin to the university. It was a blended programme, partly online and in-person. It blew me away. I felt that Irish people were very easy to talk to. I just had that connection. So I decided to come to Ireland to give my children that type of education.”

But there was no pathway available to allow her to practise as a GP here. Undeterred, Dr Malik came to Ireland and worked as a locum doctor with GP out-of-hours (OOH) service Caredoc. After this she worked with the HSE child and adolescent mental health service in Cork.

Last year she commenced the International Medical Graduates (IMG) Rural GP Programme, which she described as “just heaven sent”.

She is now working in Midleton with Dr William Hutch and the other GPs.

“It’s a beautiful experience. Dr Hutch and his team are very supportive. It’s like a small family. Everyone is caring and the patients are local, so you see them in the shop or out walking and they say ‘hello’.”

Her children have settled well in Ireland. Her son is in his first year studying pharmacy at Trinity College Dublin and her daughter is in fifth year in secondary school.

The work has provided her with opportunities to do research into upper respiratory tract infections with Cork-based GP Dr Paul Ryan. Dr Malik is also pursuing a diploma in musculoskeletal medicine.

She plans to stay in Ireland for the foreseeable future.

“You don’t feel foreign here. I don’t feel foreign in Midleton. There is a lot of commonality between people here and Sudanese culture. You can talk to your neighbour over the wall for a half hour and give out about things,” she laughed.

Dr Daniaal Omar

Dr Daniaal Omar arrived from South Africa in 2018 to “get some experience and travel”, the Johannesburg native told MI.

He worked as a locum around Limerick city and county with OOH GP service Shannondoc before working as a registrar in emergency medicine in Cavan to attain hospital experience.

Dr Omar returned to South Africa during the pandemic and considered staying there. However, Cork GP Dr David Molony contacted him when the IMG programme was established.

He joined the Mallow Primary Healthcare Centre last year and has been helping to provide vital healthcare services to patients. “I enjoy it [the work]. I enjoy the variety of patients and different conditions you see here compared to back home,” he said.

“Ireland is definitely an attractive place to work as a GP, as GPs are integrated into the healthcare system. I see a wide variety of conditions and cases, including mental health cases…. In Ireland general practice is relied upon so much.”

While admitting the IMG Programme “is a bit of a slog” and “very hands-on”, he is enjoying the work and says the ICGP has been very supportive. He plans to stay in Ireland for the foreseeable future.

Cork city, where he lives currently, is much smaller than the bustling city of Johannesburg, which has a population of over five million. But it is “a beautiful city” nonetheless, Dr Omar said.

And as for the weather compared to South Africa? “You get used to it,” he laughed.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.