Bette Browne outlines US President Joe Biden’s restoration of a global programme to fight new pandemic threats

A groundbreaking programme to help countries identify and combat emerging pandemic threats, which was shut down under the last US administration, will see its funding restored and its global battle intensified under President Joe Biden.

The Predict programme, which was launched in 2009, had identified 1,200 different viruses that had the potential to erupt into pandemics, including more than 160 novel coronaviruses. It had trained over 5,000 scientists in 30 African and Asian countries and supported staff in 60 foreign laboratories, including the Wuhan lab in China that identified SARS-CoV-2.

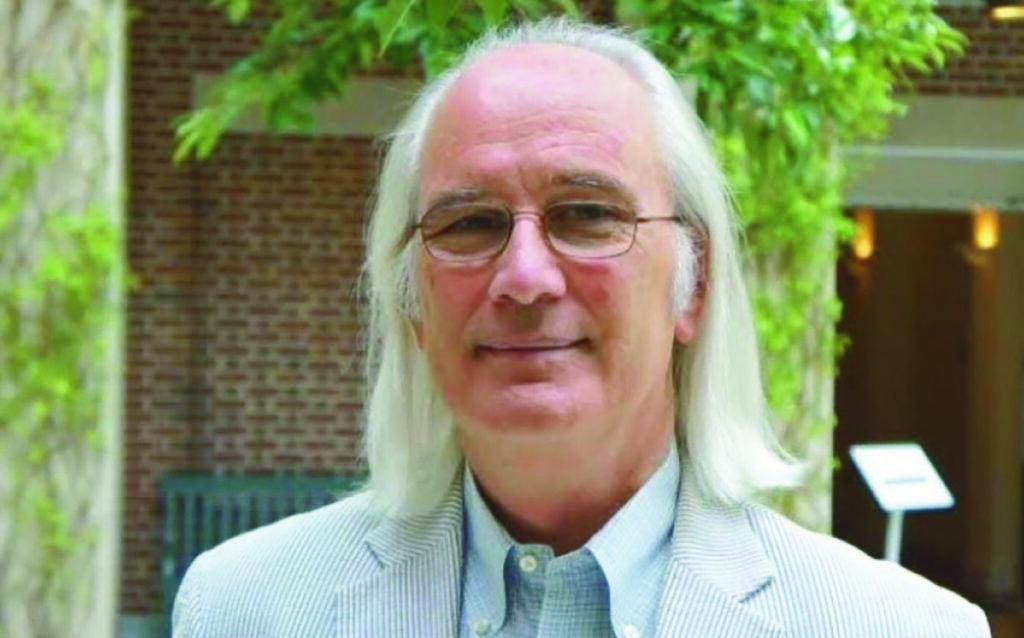

Dr Dennis Carroll (PhD), who headed the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) emerging threats division, oversaw the Predict initiative, but retired around the time it was shut down.

He told the New York Times that as early as January 2019, the programme had “essentially collapsed into hibernation” due to “the ascension of risk-averse bureaucrats”.

This was interpreted as an indirect reference to President Donald Trump’s hostility towards many aspects of foreign aid. But foreign aid is rarely altruistic as health problems in developing countries frequently impact on the health and wellbeing of people in developed countries and on their economies.

The timing of the programme’s shutdown could not have been worse, coming as it did in September 2019. This was just three months before Covid-19 emerged from China to begin its deadly march across the globe, killing millions.

Now the programme has been revamped and rebranded under the name Strategies to Prevent (STOP) Spillover. But the mission will be the same as that championed by Predict – to intensify the battle against pandemics, especially monitoring zoonotic infectious diseases that normally exist in animals, but can jump to humans.

The original Predict initiative was part of the emerging pandemic threats programme in the aftermath of the 2005 H5N1 bird flu scare and was run by USAID.

“It had as its primary purpose the identification of the most likely sources of zoonotic disease and the places and practices more likely to expose people to pathogens that can jump the species barrier,” the agency explained.

Zoonotic infections in wildlife are transmitted to humans through livestock. One obvious example is bird flu, which originated in wild birds and then moved to domestic poultry and subsequently to humans.

The work that these projects do may help our country and our world to avoid future catastrophic epidemic and pandemic events

Vision

The Predict programme used biological and behavioural surveillance and predictive modelling to identify and understand the viruses and bacteria, and their animal hosts, human behaviours, and other factors most associated with spillover events. The original Predict programme became part of the US contribution to the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA), which was launched in 2014 in response to the global threat that infectious diseases posed in an increasingly interconnected world.

“Our vision,” the GHSA said at the time, “is a world that is safer and more secure from global health threats posed by infectious diseases – one where we can prevent or mitigate the impact of naturally occurring outbreaks and accidental or intentional releases of dangerous pathogens.”

The USAID spent $200 million (€167 million) on the Predict programme over 10 years. Now a similar amount will be directed to STOP Spillover.

“The new STOP Spillover project will leverage the data collected and knowledge gained by Predict to develop interventions to reduce the risk of the transmission of dangerous pathogens passing from animals to people, including strains of influenza, Ebola, Lassa fever, Marburg, Nipah, and coronaviruses,” the USAID said.

“These viruses from wildlife have caused repeated outbreaks over the past few decades, and most lack specific, proven treatments and vaccines.

“STOP Spillover will focus on strengthening national capacity in a limited number of targeted countries to develop, test, and implement interventions to reduce the risk of the spillover and spread of zoonotic pathogens in animal and human populations.”

The agency said the new project will complement other USAID investments in addressing zoonotic diseases, including investments in disease surveillance; laboratories; preparedness for, and response to, outbreaks; reducing the prevalence of zoonotic diseases in livestock through partnerships with governments and the private sector; and the training of health workers.

The abandonment of Predict sparked wide criticism among scientists, who noted that the coronavirus was exactly the sort of catastrophic animal virus the programme was designed to combat. As well as supporting epidemiological modelling to predict where outbreaks are likely to erupt, the programme sought ways to curb practices, such as hunting for bush meat or breeding racing camels, which can spark eruptions.

After the West Africa Ebola outbreak, for example, Predict researchers determined which bat species carried the Ebola Zaire strain which caused it. Another team in Sierra Leone also discovered a new strain of the virus, which became known as Ebola Bombali. The Zaire strain was found in a bat that roosts in caves and mines, while the Bombali type was in a species that roosts in houses.

Funding cuts

After years of support from Congress, and the Bush and Obama administrations, the programme was allowed to go into hibernation early in 2019. Field work ceased when the funding ran out by September 2019 and participating organisations laid off dozens of scientists and analysts. By 30 September 2019, it had reached the end of its second five-year funding cycle.

The decision to abandon the programme was criticised by members of Congress. In a letter to USAID in January 2020, Senator Elizabeth Warren demanded to know why it had been decided not to renew the programme. She stated that while parts of the programme were apparently to be taken over by other government agencies, such as the Defence Department’s Threat Reduction Agency and the National Institutes of Health, these agencies “do not share the USAID’s goal of training poor countries to combat threats”.

Senator Angus King also condemned the decision, saying: “The work that these projects do may help our country and our world to avoid future catastrophic epidemic and pandemic events.”

Once the scale of the coronavirus pandemic became clear, Predict got a brief reprieve of sorts. Some staff were deployed to countries to provide technical assistance with testing and additional supplies. For months, those efforts were supported by a limited pool of funds the programme had left over from the previous year.

With this $2.26 million extension, Predict continued to provide technical expertise to support detection of SARS CoV-2 in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East and investigate the animal source of SARS CoV-2 using data and samples collected over the past 10 years in Asia and Southeast Asia. But then the funding dried up.

Even after Predict ended, its impact was still evident in some countries. The gene-sequencing teams that it trained in Thailand and Nepal, for example, were the first to detect Covid-19 in their countries, even before they got test kits from the World Health Organisation (WHO).

In response to criticisms, USAID said it was planning a successor programme, but few details emerged. The core programme that focused on working with local researchers around the world to collect samples and better understand viruses in animals had come to an end.

However, with President Biden’s success in the November 2019 presidential election, plans were made to invest in the successor STOP Spillover programme.

President Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris strongly supported the reinstatement of the revamped programme and they made their views clear during the presidential contest against former President Trump.

Americans need to understand how much their health security depends on that of other countries, often countries that have no capacity to do this themselves

“Barack Obama and Joe Biden had a programme called Predict that tracked emerging diseases in places like China. Trump cut it,” Vice President Harris had said, while President Biden declared at the time: “As President, I will prioritise sustained long-term investments that ensure America is strong, resilient and ready in the face of new pandemic threats.”

He also pledged to strengthen the US military’s biological threat-reduction programme and restore the National Security Council’s directorate for global health security and biodefence.

Zoonotic disease

The United Nations Environment Programme says that 60 per cent of all infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic. On average, a new infectious disease transmitted by animals emerges in humans once every four months. It predicts that the situation will worsen unless the “critical relationship between a healthy environment and healthy people” is maintained.

Zoonotic disease can be caused or worsened by changes in the environment, such as new land use or climate change. Increasing human populations, especially in urban areas of developing countries, can also contribute as this results in an enormous upsurge in demand for milk and meat, which results in more breeding.

The clustering of more people into cities, particularly huge cities in Asia, creates fertile grounds for such diseases to spread quickly. The incursion of humans into wildlife habitats is also increasing the crossover of zoonotic diseases from animals into people.

Climate change, too, is expanding the reach of disease-bearing vectors like mosquitoes into new regions and putting new populations at risk. Indeed, recent research published by The Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change found that millions of lives would be saved annually by 2040 if countries raised their climate ambitions to meet Paris Agreement targets.

Poorer countries with weak public health systems are especially vulnerable, the UN says. Such countries, especially in the developing world, receive far less funding than developed countries and their citizens live near wildlife and rely on them in their daily lives. This is another reason why, in an interconnected world, it is in the interests of the developed world to assist such countries not only from an ethical standpoint but also for their own health security, if not survival.

Control systems along the food chain and targeting the disease in livestock have enabled the developed world to curb diseases in the past and helped to stop the rise of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2002.

Health security

Four years before Covid-19 struck, the United Nations Environment Programme estimated that emerging diseases had cost the US over one hundred billion dollars and if they had become pandemics, they could have cost up to several trillion dollars. The current pandemic has illustrated the horrifying human costs, with over 2.4 million deaths reported to date.

The establishment of STOP Spillover, however, is a sign that the US may be learning from past mistakes and realising that cutting aid to developing countries is counterproductive.

“Americans need to understand how much their health security depends on that of other countries, often countries that have no capacity to do this themselves,” according to Dr Gro Harlem Brundtland, the former Prime Minister of Norway and former WHO Director-General, who issued a report in September 2019 on the world’s failure to prepare for pandemics. The report coincided with the demise of the Predict programme.

“For too long, we have allowed a cycle of panic and neglect when it comes to pandemics. We ramp up efforts when there is a serious threat, then quickly forget about them when the threat subsides,” the report said. “It is well past time to act.”

The report outlined seven urgent actions for world leaders to take to boost global preparedness. It emphasised that government heads must commit to preparedness by implementing their obligations under the International Health Regulations. It said countries and organisations, such as the G7 and G20, should follow through on their funding commitments for preparedness and agree to monitor progress.

All countries should build strong health systems and routinely conduct simulation exercises to establish and maintain preparedness.

One of the recommendations urged countries, donors, and multilateral groups to prepare for a rapidly spreading pandemic from a lethal respiratory pathogen – naturally occurring or from an accidental or intentional release – by investing in new vaccines, drugs, surge manufacturing capacity, broad-spectrum antivirals, and appropriate non-pharmacologic interventions.

It also addressed sharing genome sequences of new pathogens and limited medical countermeasures. Even as the report was issued the coronavirus pandemic was about to strike the world.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.