Ireland has backed a global campaign to classify noma as a neglected tropical disease. Bette Browne reports

The disfiguring disease, noma, struck Ireland during the Famine and today it remains so lethal in the developing world that no other infectious disease kills so many people so quickly.

Most of the victims are malnourished children between the ages of two and six.

Noma is a neglected disease that affects people living in extreme poverty. It is an infectious, but non-contagious bacterial disease that starts as an inflammation of the gums, but spreads rapidly, destroying the bone and tissue and affecting the jaw, lips, cheeks, nose or eyes, depending on where the infection started.

If left untreated, up to 90 per cent of people affected will die, usually within a short timeframe. Those who survive are left with severe facial disfigurement that can make it hard to eat, speak, see or breathe.

Documentary screening

One of those survivors is Burkina Faso native Mr Fidel Strub, who attended a recent film screening and panel discussion in Dublin organised by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). The documentary Restoring Dignity, which was screened at the Irish Film Institute on 14 March, provides an insight into the lives of noma survivors and is aimed at raising awareness of the disease. The documentary was filmed at MSF’s Sokoto project in northwest Nigeria and tells the stories of noma survivors treated at the hospital.

During the discussion, Mr Strub described the horrors of noma as follows: “The fever became unbearable and my world became literally dark as I had to close my eyes to bear the pain.”

Mr Strub is co-founder of Elysium Noma Survivors Association, the first noma survivors’ organisation. His visit to Dublin was part of a wider campaign backed by Ireland and 31 other countries to urge the World Health Organisation (WHO) to recognise noma as a neglected tropical disease (NTD) so that more resources can be released to fight it.

The first registered case of noma can be traced back nearly 1,000 years, according to the Association. Yet there is little data about the disease and even its cause is still not entirely clear.

“Earlier this year, Nigeria and 30 countries [now 31], including Ireland, shared an official request with the WHO to add the disease to the list and we are hopeful this will happen in 2023,” said Monaghan-born Dr Mark Sherlock, Health Advisor for Nigeria with MSF, who also spoke at the event.

“Ireland has already played an important role by endorsing this request, but 2023 is a key year for the recognition of noma at a global level and it’s crucial we continue advocating for more resources and research of this disease.”

Ireland’s Chief Dental Officer, Dr Dympna Kavanagh, reaffirmed Ireland’s support for noma to be included on WHO’s list of NTDs.

“As an advocate for global public health and an active participant at the WHO, we believe that a global response to noma is appropriate,” Dr Kavanagh said during the discussion.

“Ireland fully supports the inclusion of noma on the World Health Organisation’s list of neglected tropical diseases. I hope that this will be an important step in the eradication of this disfiguring and deadly disease.”

The disease now mostly occurs in Africa and Asia; however, cases have been reported on all continents throughout history, Dr Sherlock told the Medical Independent.

“For example, it was recorded in the population of Ireland during the Great Famine of 1845-1849 and documented in the Irish census of 1847. In 1998, WHO estimated that noma affects 140,000 people every year and that 770,000 patients had survived the initial infection. However, the data have not been updated since then.”

Cases can remain undetected for four reasons, according to the WHO. These include the rapid progression of the disease and the high mortality rate associated with its acute phase; the inability of both the general population and health workers to recognise noma; the lack of routine surveillance systems that include noma; and the hiding of affected children by their families because of the social stigma associated with the disease.

“Noma, the face of poverty, represents the worst violations of the rights of the child,” the United Nations Human Rights Council Advisory Committee stated in 2012. The committee citied children affected by noma as an example of the effects of severe malnutrition and childhood diseases.

In 2014, MSF started supporting the Sokoto Noma Hospital in Nigeria, providing medical care for patients coming from all over Nigeria. It provided nutritional and mental health support, surgical management, and reconstructive surgery. Since the beginning of that project, 1,066 free-of-charge surgeries have been performed for 717 patients.

People die from noma arising from the limited knowledge about the disease. Often there is uncertainty among healthcare workers in how to detect and treat it. Noma is most prevalent in low-income and remote settings, where people often face numerous barriers to access healthcare. Early detection and treatment are critical. Once the disease has progressed to the later and more severe stages, it is often too late to avoid severe disfiguration, or death.

“Noma is a disease that is preventable, treatable, and should no longer exist,” Dr Sherlock emphasised. “There is no other infectious disease that kills so many people, so quickly. People die from noma because of limited knowledge about the disease and how to detect it. More effort is needed to detect cases early and identify survivors.”

Dossier

After a three-year international advocacy campaign, a representative from the Federal Ministry of Health in Nigeria shared a dossier on noma with WHO offices in Abuja (Nigeria), Brazzaville (Congo Republic), and Geneva (Switzerland) in January this year. MSF supported Nigeria in finalising the dossier and engaging with the co-sponsors, which includes 32 countries from five WHO regions.

The WHO will take the final decision on whether to add noma to its list of neglected tropical diseases during one of its biannual meetings later in 2023.

“The inclusion of noma in the list would shine a spotlight on the most neglected of neglected diseases, facilitating the integration of noma prevention and treatment activities into existing public health programmes, and the allocation of much-needed resources,” Dr Sherlock said. “We want children to be screened in endemic countries for noma for the first sign of symptoms, when lives can still be saved.”

World Health Assembly

The request for noma’s inclusion on the WHO’s list is in line with a resolution on oral health adopted in 2021 at the 74th World Health Assembly. The resolution recommended that “noma should be considered for inclusion in the NTD portfolio as soon as the list is reviewed in 2023”.

The Assembly heard from countries affected by noma and those working in the field of noma who are keen to see the disease added to the WHO’s NTDs list. Dr Bente Mikkelsen, Director of Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD) at WHO headquarters, reaffirmed the Organisation’s commitment to support efforts to promote noma research, awareness and funding. “The success in the fight against noma is linked to the capacity of stakeholders to work together,” she told the meeting. “It is now time to unite with other sectors, not just oral health as part of NCDs, in a true collaborative effort.”

The WHO strategic and technical advisory group for neglected tropical diseases (STAG-NTDs) defines a NTD as one that disproportionately affects populations living in poverty and causes significant morbidity and mortality, including stigma and discrimination, justifying a global response. According to the definition, while NDTs are relatively neglected by research, they are immediately amenable to broad control, elimination or eradication by applying one or more of the five public health strategies adopted by the Department for Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases.

With improvements in hygiene and nutrition, noma has disappeared from industrialised countries since the 20th Century. The progression of the disease can be halted with the use of antibiotics and improved nutrition, but its physical effects are permanent and may require major plastic surgery to repair.

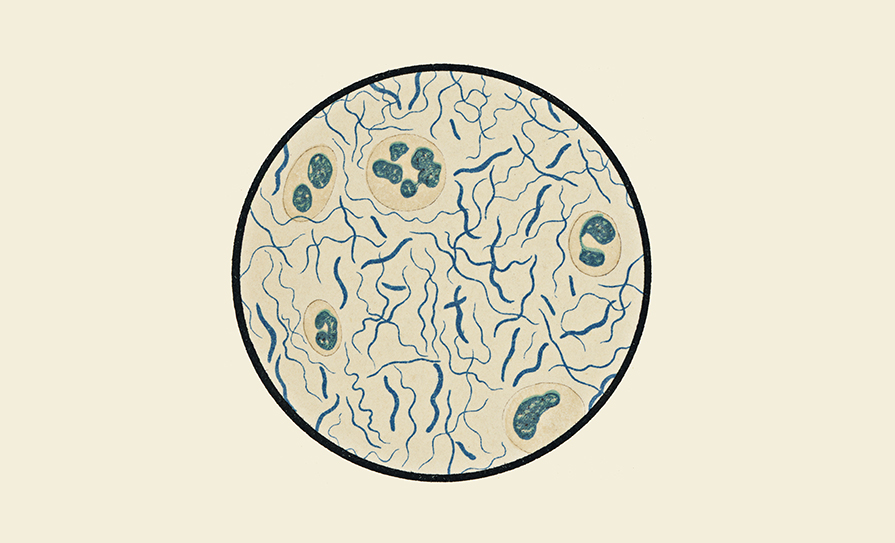

While the exact cause is unknown, studies indicate it may be due to a certain kind of bacteria, It is believed to be caused by the spirochete Borrelia vincentii in association with anaerobic bacteria, commonly a member of the fusobacteria. This disorder most often occurs in young, severely malnourished children. Often they have had an illness, such as measles, scarlet fever, tuberculosis or cancer. They may also have a weakened immune system.

With basic oral hygiene, antibiotics, and wound dressing a patient can recover from noma within a few weeks. This is helped by managing underlying risk factors, such as malnutrition and other diseases like measles. Thus, the WHO’s upcoming decision on whether to add noma to the list of NTDs will be a major step in fighting a disease which, in the words of Dr Sherlock, should no longer exist.

The noma nightmare – The testimonies of survivors

Mr Fidel T Strub was born Fidèle Touwendsida Nikiema on 24 May 1991, in Saaba, around 10km from Ouahigouya, the capital of the west African nation of Burkina Faso. He was adopted in 1998, grew up in Basel, Switzerland, and now lives near Berne. He is co-founder of the Elysium Noma Survivors Association.

“I can clearly remember a time when I was playing with my older brother and I felt a pain and discomfort in my right cheek,” Mr Strub recounts.

“A day or two prior to that I had felt a scratching feeling. When that pain got stronger, I could not continue biting as it already hurt too much. That was also when I smelled an unpleasant odour. Shortly after, that odour worsened and my father and grandmother realised something was wrong with me.

“They took me to the doctor and he gave me something. I did not get better, so we went to the doctor again and he did the same thing to me. At this stage, my father had run out of money and he was taking me around hoping that someone knew what was happening to me. I don’t know in what timeframe this happened, but it must be just over a week when the fever became unbearable and my world became literally dark as I had to close my eyes to bear the pain and hammering headache.

“Then I only remember a bus drive and later waking up in a hospital where Dr Zala fought for two weeks to stabilise me and save my life. Some years ago, I met him by chance in Geneva and he told me that he had absolutely no hope I would survive, as my condition was really bad. But he saw a fighter in me and tried his best. I was one of his first noma patients. After that, he received a specific noma training by a Swiss organisation called Sentinelles.

“During the stabilisation process, I did not know what was happening. I could only feel that the pain was gone, but eating was nearly impossible, half of the food was falling from my mouth. I never looked at myself in a mirror at that time or not that I can remember. After a few weeks in the Persis Hospital in Ouahigouya in Burkina Faso, I was transferred to Geneva where I underwent numerous surgeries between 1996 and 1998. I was literally in a white world, where I knew no one and couldn’t understand the language.

“Some faces became my anchor and one of these people is now my mother.

“The recovery was gruelling. Six years of speech therapy, every morning and evening doing mouth exercises. I hated the mirror. I don’t know how I made it through, but I managed to adapt to everything. I was a slow eater. It took me 40 minutes to complete a small plate. So I set a

goal to get faster at eating. Now I eat at normal speed. My mouth can only open between 5mm

to 8mm depending on the season and temperature. The more a fork is bent the less I can load it up. Mastering all this took me another four-to-six years.

“My teenage years were hell. I was suicidal and I did not accept myself until I was around 23 years old. Well, I still don’t, but I came to terms with the fact that this will stay. I still don’t like mirrors. I had in total 27 surgical operations and I had to constantly adapt to multiple things. It is like you have to learn everything anew all the time and I had it to do it my way as no-one around me had the experience….

“I learned to ignore the looks of people on the streets. I learned to not be hurt if someone changed seat or street upon meeting me. I just learned to become emotionally dull to make it through the day even if it cost me a lot of energy….

“I co-founded Elysium with Mulikat Okanlawon in November 2022. The reason we chose the name ‘Elysium’ was because of the meaning of this word. It comes from the Greek word and it is the home of the blessed after death. It is dedicated to all the victims who died too early and in the cruellest way possible. We hope that although they had to endure unimaginable torture while they lived, they can find the peace in the Elysian Fields.

“We want to share our experience and help people realise that even if the acute phase of noma lasts a very short time, the consequences of it are a lifelong journey for the very rare survivors like us.”

Ms Mulikat Okanlawon, co-founder of the Elysium Noma Survivors Association, now works as a hygiene officer at the Sokoto Noma Hospital in northern Nigeria.

Ms Okanlawon recalled that she first came to the hospital more than 20 years ago to receive treatment for noma.

Having subsequently completed her education at the local Gwadabawa School of Health Technology, Ms Okanlawon was offered her current job, where she provides psychosocial support to noma patients and acts as an advocate.

“I used to cry every day. I didn’t associate with anyone due to the stigma. I was alone.

“But after I was treated here, everything changed. I began to admire myself. I began to relate to other people. I continued my schooling. I began to do everything that I couldn’t do before.”

“My goal is to inspire people,” she says.

“I want to share my story with all noma patients: There is still life after noma. When there is life, there is hope.”

(Sources: MSF, WHO)

Photos by Fabrice Caterini/Inediz

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.