The national dementia model of care aims to ensure people have equitable access to services. Catherine Reilly examines implementation to date

The HSE Model of Care for Dementia in Ireland was devised in response to “huge variability” in timely access to diagnosis and care, according to Clinical Lead for National Dementia Services and Consultant Neurologist, Dr Seán O’Dowd.

“The work done prior to the model… highlighted there was huge variability and discrepancy in terms of timeliness of access,” Dr O’Dowd told the Medical Independent (MI). “That obviously isn’t something that is very equitable or acceptable.”

The model of care, published in May 2023, includes 37 targets and a series of practice recommendations to advance the assessment, treatment, care and support of people with dementia and their families. It sets out maximum waiting times for access to diagnostic services; minimum multidisciplinary staffing requirements; guidance and key steps for communicating a diagnosis; and targets and recommendations for post-diagnostic support.

Dementia remains “hugely” undetected and under-diagnosed in Ireland, noted the document. Over 64,000 people nationally are estimated to be living with dementia, but reliable data is lacking. Speaking to MI in September, Dr O’Dowd said the establishment of a dementia registry is “essential” for service planning. He was hopeful this could be progressed in 2025 (€200,000 has since been allocated to implement a registry in Budget 2025).

Dr O’Dowd said the State had provided consistent funding for dementia services over the past number of Budget cycles. However, he confirmed the HSE recruitment moratorium had impacted on planned developments.

Prior to the launch of the model of care, 10 locations were identified with very little or no specialist memory services, and these were prioritised for new services. To date, a memory assessment and support service (MASS) has been established in three of these locations (Mayo, Sligo, and Cavan/Monaghan). New services were also required in Kerry, Galway, Limerick, Waterford, Wexford, Donegal, and Longford/Westmeath.

When launching the model of care in May 2023, the HSE had outlined that nine new MASSs were funded.

Dr O’Dowd said the goal was to get services in priority locations established through the 2025 estimates process. “They have just been held up, like so many other aspects [in healthcare] in the last while, with the hiring freeze and so on.”

At press time, MI understood €1 million in new development funding was being provided to support consultant recruitment for new services.

Assessment

There are three levels of assessment set out in the model of care. ‘Level one’ is primary care where an initial assessment is conducted and/or led by a GP; this process may include support and information from community-based healthcare teams. In consultation with the patient, the GP may then make a referral to a level two or level three specialist service for further assessment.

Most specialist assessments will be conducted in a MASS/other ‘level two’ service. Under the model, the MASS also provides post-diagnostic support and follow-up through a specialist dementia post-diagnostic service and a brain health service. The brain health (risk reduction) service is aimed at people with significant risk factors for dementia, and people diagnosed with dementia, subjective cognitive impairment, or mild cognitive impairment.

A minimum of one MASS is recommended per 150,000 population, equating to around 30 ‘level two’ services nationally. This will require resourcing for new dedicated MASSs and the ‘uplifting’ of existing memory services. Dr O’Dowd said this would involve a multi-annual process due to the scale of funding required.

‘Level three’ regional specialist memory clinics (RSMCs) provide assessments for people aged 65 years or under with a suspected dementia or people with atypical or unclear presentations.

A minimum of five RSMCs are recommended and two are fully established to date (at St James’s Hospital and Tallaght University Hospital [TUH], both in Dublin). As of autumn 2024, the RSMCs in University Hospital Galway and Mercy University Hospital, Cork, were not yet fully operationalised. A fifth RSMC is likely to be established in north Dublin, based on demographic needs, but a decision has not yet been made. In addition, a National Intellectual Disability Memory Service is established at TUH.

Patients with suspected dementia should be seen within two weeks of seeking an appointment in primary care and within six weeks of referral to a specialist service. Eighty per cent of people should receive their results from specialist services within three months.

According to the National Dementia Office (NDO), data collection on compliance with targets/indicators commenced in pilot form in May 2024. It is likely to be early next year before a “meaningful analysis” of these metrics will be performed.

Roll-out of the model of care is coming at a time of significant scientific activity on modifiable risk factors and disease-modifying treatments for early Alzheimer’s disease (AD). This growing evidence-base is also serving to further illuminate the importance of early diagnosis. The European Medicines Agency has not yet licensed any anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody drugs for early AD, but the NDO has been preparing for this strong possibility for some time (see panel).

The model of care document may need to be updated as evidence emerges on the effectiveness of such treatment options and to support the roll-out of any modifiable risk interventions.

The document “acknowledges these developments, whilst maintaining a clear focus on serving the needs of those for whom these interventions and innovations will not be applicable”.

Roll-out of the model of care is coming at a time of significant scientific activity on modifiable risk factors and disease-modifying treatments for early Alzheimer’s disease

Communication

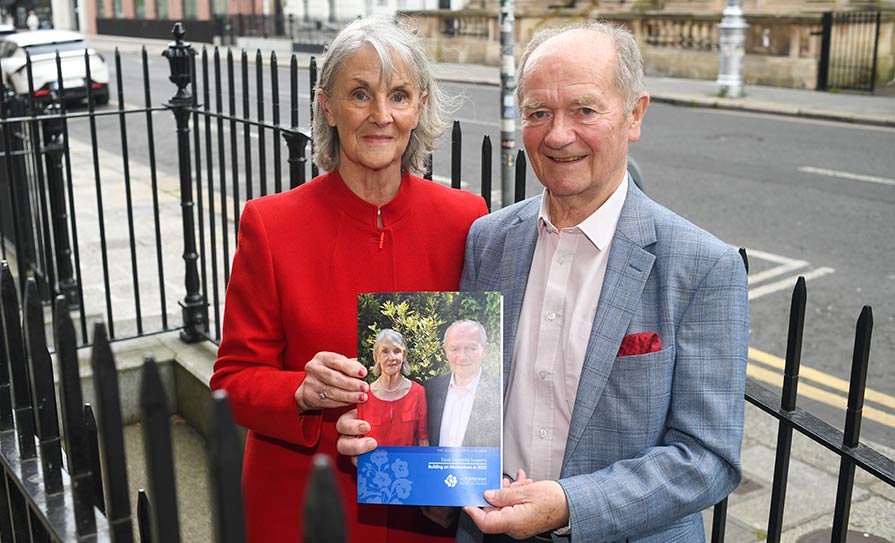

“When Mary got diagnosed with Alzheimer’s… the way we were told about it left us devastated,” says Mr Tony McIntyre of his wife Mary’s diagnosis in 2015. “We were given no advice, and he told us another doctor would contact us, and that contact was many months away.”

A number of months after Mary’s diagnosis, they received a leaflet on the Alzheimer Society of Ireland (ASI) while attending an appointment at another hospital. They contacted the ASI and were linked to a dementia advisor, Ms Joanne Brennan, who provided a comprehensive picture of the condition and recommended joining the ASI.

“Mary did that, she joined the dementia working group with the Alzheimer Society and it changed our lives at that time,” adds Tony, who lives in north Dublin. According to the ASI, most health and social care professionals communicate a dementia diagnosis with care. However, it stated that research and anecdotal evidence have demonstrated this is not always the case.

Over the years, Mary and Tony have become involved in a number of ASI advocacy groups, including the dementia research advisory team (DRAT). The DRAT is a group of people living with dementia and carers/supporters who are actively involved in research as co-researchers. The DRAT has produced a diagnosis checklist that includes basic recommendations for health and social care professionals to consider when disclosing a dementia diagnosis, alongside contact information for the ASI.

While Tony said he has been informed of improvements in communication, he is aware of recent examples in hospital services where practice has remained poor.

Impact

Two days a week, Mary attends the ASI’s Fáilte day service in Dublin 15. Tony said this service provides Mary with access to stimulating activities. It also offers a break for carers, which Tony said is crucial for mitigating the health risks faced in the caring role.

Music is among the activities on offer. “Mary has started humming and singing words to songs which she never did before and she is much better within herself because of the day care centre.” However, he emphasised that many people have no access to a day service or the ‘day care at home’ service.

For Tony, another critical resource has been an online ASI family carers’ training course, which he undertook last year. These supports are also over-subscribed – the ASI confirmed there is a waiting list for both its online and in-person family carer training courses.

“Meeting the dementia advisor and doing that course, at both those stages, it changed my life,” emphasised Tony.

He said although Mary’s condition has progressed, “we are enjoying life again.”

“One of the things it taught you is that the Alzheimer’s keeps changing so you’ve got to change with it. That is what I am trying to do all the time,” he outlined. “It is still in my mind what we should be doing – more socialising, more physical activity, more music.”

Earlier this year, Tony reached the final of a Toastmasters International speech contest for Ireland and the UK. In his speech, he described the realities of dementia, the importance of support, and the positive impact of the family carers’ course. A key message was no matter how down a person may feel, “there is always help, look for it and listen to what you are being told, and implement it.”

When Tony has delivered this speech, people have approached him saying they were in tears due to its impact. He said this response also illustrated the problems faced by families getting help and support.

The ASI has been seeking increased State funding to widen its network of dementia advisors and day services, among other provisions. In 2023, €21.2 million of the ASI’s total income (€ 26.3 million) was received from public bodies (mainly the HSE), with €3.7 million raised through fundraising.

Its various services throughout the country have “waiting lists and ongoing capacity challenges”.

The ASI had urged the Government to continue moving the model of care “from paper to practice” by investing €5.5 million in dementia in Budget 2025, alongside critical social protection, policy, and workforce planning measures.

At press time, the ASI welcomed the overall €2.3 million in funding allocated for dementia in Budget 2025, which includes some provisions to support expansion of its services.

Dementia nurse roles

A positive recent development is the installation of six assistant directors of nursing across the Hospital Groups for quality improvement in dementia care. Their remit is to lead, support, and facilitate dementia inclusive initiatives within the acute setting.

Dr O’Dowd is also keen to progress a third iteration of the national audit of dementia care in acute hospitals (INAD). The second report was based on data collected in 2019. Among its findings was that just 6 per cent of hospitals had a dementia inpatient care pathway and only 22 per cent had a dementia recognition system across some or all areas.

Regarding concerns raised by patient advocates about communication in healthcare, Dr O’Dowd said sensitive and person-centred approaches to communicating a diagnosis is “an essential aspect” of patient care.

Five of the targets in the model of care specifically focus on how this should be conducted.

“It is explicit that the process should be medically led and by senior clinicians (consultant, SpR or registrar). Higher specialist training curricula in each of the anchor specialties in the dementia sphere (neurology, geriatric medicine, and old age psychiatry) mandate specialist knowledge in dementia diagnostics, as well as appropriate communication skills training.”

‘Competing narratives’ around new disease-modifying therapies for AD

Anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are the first medications to show some evidence of efficacy in slowing the progression of early Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Their advent – and the likely future adoption of diagnostic plasma biomarkers – could radically alter the delivery of clinical dementia services.

In July 2023, lecanemab (Leqembi) from Eisai and Biogen became the first mAb to receive traditional approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for early AD. In a phase three randomised controlled clinical trial, lecanemab demonstrated a “statistically significant and clinically meaningful reduction of decline” from baseline to 18 months on the primary endpoint, the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) score, compared to placebo, according to the FDA. The FDA noted the most common side-effects of lecanemab were headache, infusion-related reactions, and amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA). The latter can “rarely” lead to serious and life-threatening events and this risk is the subject of a black-box warning for lecanemab.

However, the EMA recently declined to approve lecanemab. In July 2024, the EMA’s committee for medicinal products for human use (CHMP) stated that the observed effect of lecanemab on delaying cognitive decline did not counterbalance the risk of serious adverse events associated with the medicine.

The most important safety concern was the frequent occurrence of ARIA. “Although most cases of ARIA in the main study were not serious and did not involve symptoms, some patients had serious events, including large bleeds in the brain which required hospitalisation. The seriousness of this side-effect should be considered in the context of the small effect seen with the medicine.”

The CHMP was also concerned by the fact the risk of ARIA is more pronounced in people who have a certain form of the gene for the protein apolipoprotein E called ApoE4. The risk is highest in people with two copies of the ApoE4 gene, who are known to be at risk of developing AD and would therefore be likely to become eligible for treatment with Leqembi.

In August, however, the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency approved lecanemab for people with early AD, except for homozygous ApoE4 carriers due to their higher risk of ARIA. In tandem, draft guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) determined that the benefits of lecanemab were too small to justify the costs. “Lecanemab provides on average four-to-six months slowing in the rate of progression from mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease, but this is just not enough benefit to justify the additional cost to the NHS,” stated Ms Helen Knight, Director of Medicines Evaluation at NICE.

A marketing authorisation application for donanemab, developed by Eli Lilly, is being reviewed by the EMA. Donanemab (Kisunla) has recently been granted traditional approval for early AD by the FDA, which reported that patients treated with the drug showed a statistically significant reduction in clinical decline. It found the benefits outweighed the risks, most notably ARIA (which is also the subject of a black-box warning).

Preparations

Clinical Lead for National Dementia Services, Dr Seán O’Dowd, told the Medical Independent the National Dementia Office (NDO) has been preparing for new disease modifying treatments for several years. It has convened focus groups and stakeholders to examine the staffing and infrastructural investment required to deliver these types of medications when licenced in the EU.

“It is something the Department of Health are very acutely aware of and very keen to support in principle.”

Dr O’Dowd said the recent EMA decision to refuse marketing authorisation for lecanemab was not anticipated. He said it had “put a lot of us in the clinical community on the backfoot”.

A spokesperson for Eisai confirmed it has sought a re-examination of the decision by the EMA CHMP.

Given the absence of a licenced drug, Dr O’Dowd did not envisage resources being secured in the short-term for implementation of disease-modifying therapy.

Asked about the benefit eligible patients may get from a drug such as lecanemab, Dr O’Dowd said lecanemab and donanemab are probably “prototype medicines”.

“I do think if they were licenced, they would have a role. I do think the benefit, in carefully selected patients, can and would be clinically meaningful, but I think the emphasis would have to be around the selection of cases. We know from the sub-populations particularly in the donanemab study, it is the group who are identified earlier with lower burdens of tau pathology… who have responded most compellingly to these anti-amyloid therapies.”

Initially such treatments (currently delivered by infusion) would be administered in a very small number of expert centres and potentially in one pilot site at the outset. Significant clinical and radiological expertise would be required.

“Obviously a biologically secure diagnosis needs to be made in the first instance before they can be given. So that means a biomarker has to be identified, be that in CSF or in PET imaging. That is something that requires a lot of expert interpretation and then the roll-out and safe delivery of these medicines involves quite a lot of surveillance, both clinical and radiological, because a lot of the side-effects that are seen are radiological and may be asymptomatic, but nonetheless need to be monitored very carefully.”

While there were “competing” narratives and clinical views about the effects of these drugs, Dr O’Dowd believed it was also a “very exciting” period given that disease modification has now been demonstrated in clinical trials for the first time.

Prevention and risk factors

In July, the third Lancet Commission on dementia prevention, intervention and care, reported nearly half of cases could be prevented or delayed by addressing 14 risk factors starting in childhood. The report added two new risk factors associated with 9 per cent of all dementia cases – high low-density lipoprotein from around age 40 and untreated vision loss in later life.

This is in addition to 12 risk factors published by the Lancet Commission in 2017 and 2020 (ie, lower levels of education; hearing impairment; high blood pressure; smoking; obesity; depression; physical inactivity; diabetes; excessive alcohol consumption; traumatic brain injury; air pollution; and social isolation). The Commission has made a series of recommendations for governments and individuals, including provision of a good quality education for children and remaining “cognitively active in midlife”.

The NDO has commissioned a population survey on awareness of brain health and modifiable risk factors in Ireland. The full results are expected to be published in early 2025. The NDO has also convened a special interest group on brain health, which is aiming to design a uniform approach to interventions offered by the specialist services.

Dementia prevention and care is not part of the chronic disease management programme in general practice. However, this is “definitely something on our radar” for the future, according to Dr O’Dowd. Any such development would require discussions with the GP community and resourcing, he added.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.