Healthcare is centre stage in the race for the White House. Bette Browne looks at the health policies of the Democratic and Republican contenders amid the Covid-19 crisis

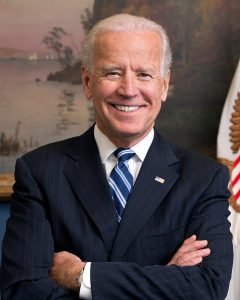

The battle lines over healthcare in the US presidential election have been drawn and can be encapsulated in just two words — cut and expand. President Donald Trump is driven by a desire to weaken and repeal the landmark health insurance law of his predecessor Barack Obama, while his Democratic opponent Joe Biden is vowing to protect and expand that law.

But now a more complex front has opened up in their battle, with the relentless and deadly march across the nation of the coronavirus pandemic.

President Trump admitted during a coronavirus briefing at the end of March that his administration remains wedded to supporting a lawsuit that would essentially kill the decade-old Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as Obamacare, even while thousands were dying and the US economy was imperilled by this health crisis.

Biden, on the other hand, has said the pandemic highlighted the importance of affordable healthcare and called on the President to drop the lawsuit, which, if successful, would see at least 20 million Americans losing their health insurance at the very time when it is desperately needed.

Writing on the 10th anniversary of the Affordable Care Act, which Obama signed into law on 23 March 2010, Biden said it was “unconscionable” that the Trump administration would “pursue a lawsuit designed to strip millions of Americans of their health insurance and protections (under the Act),” including the ban on insurers denying coverage or raising premiums due to pre-existing conditions.

“No American should have the added worry right now that you are in court trying to take away their healthcare,” declared the former Vice President, who is now the presumptive Democratic candidate to face Trump in the November election.

“You are letting partisan rancor and politics threaten the lives of your constituents, and that is a dereliction of your sworn duty. I am therefore calling on you to drop your support of litigation to repeal the ACA.”

If the ACA did not remain in force, Biden charged, millions more Americans would be facing the prospect of contracting Covid-19 without health insurance.

Not that the ACA was by any means a perfect solution. Obama himself admitted this again on the 10th anniversary of the law. It was not perfect, the former President wrote, “but it saved lives, expanded access, cut down on medical-related bankruptcy, and made our nation healthier and more equitable. It is progress worth protecting and building on until we finish the job of covering every single American once and for all.”

“It was informed by the stories I heard on the campaign trail and reinforced by the letters I would read in the White House: Parents denied coverage due to a pre-existing condition; young people left without health insurance after finishing school; entrepreneurs and small business owners unable to afford coverage for their workers.

“Those stories reflected the complexity of America’s fractured healthcare system. But the reason I pushed for what became the Affordable Care Act was a simple, deeply-held conviction: In the richest country on Earth, high-quality, affordable healthcare shouldn’t be a privilege for a few; it should be a right for all.”

But now, 10 years after the law was enacted and four years after Obama left office, the debate still remains at the centre of yet another presidential election.

Intensive care beds

The non-partisan Kaiser Family Foundation, which provides information and analyses on US health issues, points out that the pandemic has come at a time when more than half the counties in America have no intensive care beds, posing a particular danger for more than seven million people who are aged 60 and upwards — older patients who face the highest risk of serious illness or death from the rapid spread of Covid-19.

Even in communities with ICU beds, the numbers vary wildly, with some having just one bed available for thousands of senior residents, according to the Kaiser Foundation analysis, based on a review of data hospitals report each year to the federal government.

Overall, 18 million people live in counties that have hospitals but no ICU, the analysis shows. Nearly 11 million more Americans live in counties with no hospital at all, some 2.7 million of them seniors.

Prof Karen Joynt Maddox, Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, Missouri, said hospitals with larger numbers of ICU beds tend to concentrate in higher-income areas, where many patients have private health insurance.

“Hospital beds and ICU beds have cropped up where the economics can support them,” she told USA Today. “We lack capacity everywhere, but there are pretty big differences in terms of per capita resources.”

In America, affordable health insurance is essential in ordinary times. But in a health crisis sparked by this lethal pandemic, it can make the difference between life and death. Little wonder, then, that it is right at the centre of this election campaign.

Moderate path

While Biden has all but tied-up his party’s nomination to be its standard-bearer in November, he did have to overcome a strong bid by rival Senator Bernie Sanders, who championed a universal healthcare insurance plan dubbed ‘Medicare-for-All’. It was based on the idea of expanding the federal government’s Medicare health insurance programme that pays for hospital and medical care for people who are older and for some people with disabilities.

Biden, however, chose the more moderate path of protecting and expanding Obama’s healthcare law and ultimately, his stance was overwhelmingly backed by voters in Democratic primary contests across the country to make him the victor over Sanders.

Polls showed people preferred a mix of private and government-funded plans, rather than one national plan that some felt would cost them more. Kaiser Family Foundation polling, for example, found that despite broad general support for universal coverage, when people were told that it might result in loss of their private insurance, delays in care or increased taxes, support for it declined significantly.

They did not appear to heed Sanders’ explanation that the plan would be paid for by tax increases directed at the assets of the country’s richest individuals and the profits of large corporations. Still, while Sanders lost the battle, he undoubtedly succeeded in putting universal health coverage front and centre on the election agenda and pushed Biden into making it a major priority.

President Trump, meanwhile, cast the notion of universal coverage as “socialised medicine” that would see the government interfering in people’s private choices about the kind of health insurance plan they wanted.

It seemed to have been lost on many people that while making this argument, President Trump was at the same time seeking to kill the Affordable Care Act that gives million of Americans access to affordable insurance.

Biden, on the other hand, believed that if Medicare-for-All were to be eventually achieved in America, the journey would have to be made in slow, incremental steps, and so he pledged to defend and protect Obamacare and seek to expand it if he were elected President.

According to the National Centre for Health Statistics, more than 90 per cent of Americans have health insurance. Slightly more than half of Americans have coverage through their own job or that of a family member. Another 17 per cent have coverage through Medicare, the federal programme that covers seniors and some people with disabilities, while 17 per cent have coverage through Medicaid, a joint state-federal programme that covers low-income people. Around 5 per cent buy coverage on the individual market, either through the marketplaces established by the ACA or directly from an insurance company.

About 9 per cent of Americans —almost 30 million people — have no insurance. The share of Americans without insurance has fallen by more than two-fifths since enactment of the ACA, largely because the law expanded Medicaid to more low-income people and created financial assistance for most people who purchase individual market coverage.

Almost everyone who currently has insurance receives some form of public subsidy for that coverage. The federal government covers around 85 per cent of the cost of Medicare, state and federal governments together cover nearly the full cost of Medicaid, and most people who purchase individual market coverage receive federal subsidies under the ACA.

Even people who get coverage at work receive a substantial federal subsidy. Without these subsidies, far fewer people would have insurance in large part because insurance is so expensive. In 2018, the average annual premium for employer coverage for a single worker, including employer and employee contributions, was $6,900 (€6,300).

The average annual premium per person buying coverage on the individual market could be as high as €9,000. But even with existing subsidies, many insured Americans also face high deductibles and other cost-sharing additions on top of their premium.

Universal coverage could be achieved now by expanding Medicaid and Medicare in all states, increasing assistance for buying coverage under Obamacare, ensuring that people enroll in affordable coverage for which they are eligible, and by addressing coverage for undocumented immigrants. That is essentially what Biden is aiming for in incremental steps but it is also essentially what President Trump is against.

Biden is well aware that Democrats managed to regain control of the House of Representatives in 2018, in a victory largely fuelled by voter concerns over losing health coverage if Republicans dismantled Obamacare.

But then when their campaign for the presidential nomination began in 2019, many of the Democratic candidates essentially fought among themselves over who had the best plan for universal healthcare.

Biden was more astute, perhaps because as Obama’s Vice-President, he knew how tough it had been to secure passage of the ACA. So he consistently kept the focus on Obamacare after the successful congressional elections and pledged to protect it and expand it.

Analysts say his success in locking-up the nomination will also result in boosting Democratic candidates in the House and Senate races, which also take place on 6 November, the same day as the presidential election.

Eligibility

Biden wants to increase and broaden eligibility for financial assistance to buy individual insurance coverage. Steps like these would reduce costs for the 5 per cent of Americans who buy individual market coverage and reduce the cost of coverage for about half the uninsured.

He is also seeking to cover people in states that did not use Obamacare funding to expand Medicaid to all low-income people. In addition, he wants to encourage people to take up coverage for which they are eligible by possibly increasing financial assistance to them.

About one-sixth of uninsured people are undocumented immigrants, including possible thousands of Irish people. Biden may work to cover this group by creating a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, which would ultimately make them eligible for existing coverage programmes. Other approaches would expand the circumstances under which undocumented immigrants qualify for these programmes.

President Trump, by contrast, has been advocating rules that could deny legal status to immigrants who use Medicaid, food support stamps, housing vouchers or other forms of public assistance. The President is also committed to cutting federal healthcare spending, especially on Medicaid, which helps poorer Americans and which Obamacare sought to expand. Specifically, the President wants it to cap spending on the programme and restrict those entitled to assistance.

These spending caps would fundamentally change how the programme is financed, ending Medicaid’s days as an open-ended entitlement by putting new limits on how much the government is willing to spend on healthcare for certain enrollees. Medicaid would no longer pay whatever is necessary to provide medical care to those on or near the poverty line who qualify for its benefits. Instead, spending would be limited in states that got a waiver from the federal government and they could impose cuts on benefits.

President Trump has already tried to fundamentally alter the Medicaid programme through work requirements. One major change the administration has proposed would limit states’ ability to extend food stamp benefits beyond a three-month period for certain adults. The plan, which is included in the administration’s $4.8 trillion budget for 2021, includes major cuts to health and disability benefits.

It would cut support for over 700,000 people and is one of three programmes proposed by the administration to limit food support. While the other two plans are not yet finalised, when combined, the plans would constrict food stamp benefits for an estimated 3.7 million people. In addition, the system also provides school meals to over a quarter of a million children whose parents may be going through temporary financial hardship.

Block grants

The President also wants to replace the federal funding of such social programmes with block grants to states. Under block grants, states would get a fixed amount every year from the federal government to cover the expansion of the population.

The federal share, however, would be indexed to inflation, usually at a rate that would grow slower than medical costs. So over time, the federal share of Medicaid funding, for example, would start to decrease. The fear, then, among Medicaid advocates is that states could make up those shortfalls by reducing benefits and enrollment.

Conservatives contend that block grants are a good way to rein-in government spending and to give states more control over how the programme is administered. But analyses of block grant legislation showed billions of dollars in Medicaid would be cut over time and millions fewer people would be entitled to be enrolled in Medicaid.

So while Democrats are talking about expanding government health programmes like Medicaid and Medicare, President Trump keeps proposing different ways to cut them. The latest proposal for Medicaid block grants is just another example.

However, the Medicaid and Medicare programmes as they stand are very popular, especially among many of President Trump’s elderly supporters, while the idea of block grants is not. In addition, as the election approaches, President Trump may also be judged to have been on the wrong side of the argument on the best way to deal with the coronavirus pandemic.

Pandemic response

The President has said he thinks he is doing a “hell of a job” and has called himself a “wartime President”. However, critics say he lost valuable time in the battle against the virus in its early months, by dismissing it as a “hoax” by Democrats trying to damage his election chances.

He had begun to deal with it more effectively by mid-March but then he seemed to take a step backwards later that month by saying he wanted restrictions to be rolled back by Easter because “we cannot let the cure be worse than the problem itself”.

President Trump’s controversial assurance that the national economy would be up-and-running again by Easter sparked wide criticism from both Republicans and Democrats, as well as from health experts who argued that loosening social distancing would result in even more deaths and greater economic turmoil across the country.

The President’s coronavirus response co-ordinator at the White House, Dr Deborah Birx, also warned that hundreds of thousands of people in the US could die from the outbreak. As the enormity of the unfolding human catastrophe appeared to dawn on the President, he began to rely again on advice from scientists and health experts like Dr Anthony Fauci, the Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

“We felt that if we prematurely pulled back, we would only form an acceleration or rebound of something, which would put you behind where you were before, and that’s a reason why we argued strongly with the President that he not withdraw those guidelines,” Dr Fauci told CNN, adding: “He (the President) did listen.”

Biden was quick to welcome the turnaround. “It would be a catastrophic thing to do for our people and for our economy if we sent people back to work just as we were beginning to see the impact of social distancing take hold, only to unleash a second spike in infections,” Biden declared. “That would be far more devastating in the long run.”

As the coronavirus pandemic continues to devastate America, it may well become an even more dominant factor shaping the debate over healthcare in this presidential election.

It may also have a far-reaching impact, not only in America but also across the globe, long after the battle against it ends and the US presidential election is over.

The pandemic is almost certain to underline for Americans the necessity for affordable healthcare. To that extent, Biden’s plan to expand Obamacare may resonate more with voters’ concerns.

Ultimately, however, President Trump’s response to Covid-19, which centred much of the time on blaming US state governors, China and the World Health Organisation, may end up being the biggest factor influencing voters in the months ahead of the November election.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.