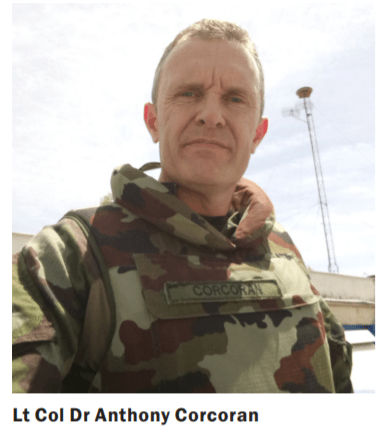

Lt Col Dr Anthony Corcoran, Medical School Commandant at the Central Medical Unit, Irish Defence Forces,

knows all about the risks of serving on peacekeeping missions internationally. He speaks to Bette Browne about

his career in military medicine in the second part of her series, ‘On the frontlines’

A chance conversation about a man in a uniform on a Dublin street, over 20 years ago, led Anthony Corcoran to become a doctor in the Irish Defence Forces. Today he is Medical School Commandant of the Defence Forces Central Medical Unit and training those who want to protect lives and safeguard international peace.

“That encounter on North Circular Road turned out to have a big impact on me and I suppose if it hadn’t happenened

I might not be where I am today,” Lt Col Corcoran told the Medical Independent (MI), when recalling the period in his life after he had qualified as a doctor.

“There was no specific area of medicine that I was feeling drawn to, so I was at a bit of a loss as to what I wanted to do next. I was talking one day with a former college classmate who said he’d spotted another former classmate walking along North Circular Road in a uniform, and that immediately piqued my interest.

“When I contacted the classmate he told me that he had joined the Defence Forces as a doctor and described what

the job entailed. It sounded different, exciting, and definitely something that interested me.

“I got in touch with the then Deputy Director of the Medical Corps and met with him a couple of times ahead of a formal interview and I finally joined in June 2000. It was interesting, it was different.

It wasn’t just one area of medicine, it was lots of different areas. When you get into the job you recognise that it involves so many different strands of medicine and that you have to develop a competency in almost everything.”

Dr Corcoran had qualified from Trinity College Dublin in 1996 and undertook his intern year in St James’s Hospital, Dublin, and Midland Regional Hospital, Tullamore, followed by six months in Australia.

When he returned to Dublin, he spent a year working in the National Rehabilitation Hospital, Dun Laoghaire, and six months in St Mary’s Hospital, Phoenix Park. Then he began his medical career with the Defence Forces.

Central Medical Unit

The Central Medical Unit (CMU) is a branch of the Army but its work in delivering medical services involves engagement across the three services of the Defence Forces – the Army, the Air Corps and the Naval Service.

The CMU is the largest element of the Defence Forces Medical Services with more than 200 personnel, including doctors, paramedics, nurses, pharmacists, physiotherapists and mental health teams Since joining the Defence Forces, Lt Col Corcoran has completed six overseas tours of duty to support UN peacekeeping or humanitarian missions. His first two missions were to Lebanon in 2000 and 2001.

He then went to Eritrea in 2002, followed by Liberia in 2004 and Chad inEach of those deployments ranged

from three-to-six months, but he has also had shorter deployments to Bosnia, Kosovo, and East Timor.

His sixth and most recent deployment was to Syria in 2020. “While there were no serious incidents during that deployment, previous Irish Quick Reaction Forces had to rescue and evacuate UN personnel from one of their posts, and there were also incidents of firing going on around Irish personnel.

Fortunately, because of the professionalism of their drills and their training, nobody was killed or seriously injured.”

But on international peacekeeping or humanitarian missions, the risks are never very far away. “The threat level on an overseas military deployment can vary from mission to mission and throughout the course of a particular mission, but it’s always there. Militaries don’t tend to deploy to areas of total peace and stability.

If a region has an international military force there, then there has to have been a reason for that.“It may be as a result of civil war, international conflict, a humanitarian crisis, or any combination of these. But, whatever the reason, it does create an environment that has a danger and threat level that is higher than what a doctor would normally experience working in Ireland.

“Over 80 members of the Defence Forces have died on overseas service. As one overseas commander put it, ‘every time we go out the gate of the camp on patrol, there is a risk of not everyone coming back.’

“So a significant focus for the Defence Forces is on the risk assessment and risk management measures to be implemented in order to mitigate the dangers in the mission area. These measures include carrying weapons, wearing body armour and travelling in armoured vehicles, all things that were completely unfamiliar to me before joining the Defence Forces.”

Specialty training

Today, these safety measures are second nature to Lt Col Corcoran, who now works in the CMU as its Medical School Commandant. One of his roles is that of National Specialty Director for the Military Medicine Training Scheme, which is one of the entry streams for doctors to join the Defence Forces, along with the direct entry process.

There are currently 23 medical officers in the Defence Forces who have joined through one of these pathways. In 2015, military medicine was recognised by the Medical Council as a specialty in Ireland and in 2017 Lt Col Corcoran was part of the team that submitted a training programme for accreditation. “We were accredited and we now have a military medicine training scheme aligned with the Irish College of General Practitioners.

Our first trainees commenced in 2017.”

Military medicine is a five-year programme. It involves two hospital-based SHO years, including rotations through emergency medicine, general medicine, and psychiatry, followed by three years of higher specialist training (HST).

“For the HST years, the trainees rotate through placements of six months duration, alternating between the Defence Forces and a GP practice,” Lt Col Corcoran explained. “They do that for a period of three years.”

As one of the first trainees to join the scheme in 2017, Captain Lisa McNamee from Dunboyne, Co Meath, will become the first person to finish the programme next year, followed by Dubliner Captain Fiachra Lambe, who started the year after Captain McNamee.

Their training is a combination of a number of different elements, Lt Col Corcoran said. “There’s an obvious focus on primary care, but with a strong influence of occupational medical care, as well as first-line emergency medicine and mental health thrown into the mix.

There’s what we call force health protection, which would be similar to public health, and tropical and travel medicine. We also get our people to qualify in aviation medicine as well as underwater medicine.

It’s an extensive curriculum designed to give a medical officer the skills and competency that he or she will need to practise medicine in a military environment.”

The role of medical officers involves a combination of primary care and occupational medicine. “Our doctors at all times are having to do both. When they see somebody in a primary care setting, they’re also having to be very much aware of the occupational impact of what’s going on. They also have to be aware of the impact for the person’s colleagues or for a particular mission.

“As doctors we’re doing the best for the patient’s health and their wellbeing. But in many ways, our primary focus is getting this person back to work as soon as possible so the unit can continue to do the job it has to do. We’re looking to keep the organisation operationally effective.”

UN missions

Military doctors treat Defence Forces patients in barracks across Ireland and they can also be deployed on overseas missions to provide support for peacekeeping troops. “The most frequent deployments for Irish troops are as part of a UN mission, known as peace support operations. The two main missions that we are engaged in at the moment are with UNIFIL (United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon), which is the mission in Lebanon, and UNDOF (United Nations Disengagement Observation Force), which is the mission in Syria.”

The main focus for the medical officer is to provide medical support for troops during these UN missions. Ireland has a long tradition of participation in UN and UN-supported peacekeeping missions, both civilian and military, including multinational peace support, crisis management and humanitarian relief operations in support of the UN and under UN mandate.

Indeed, Ireland is the only nation to have a continuous presence on UN and UN-mandated peace support operations since 1958, assisitng missions across the Middle East, Central America, Africa, and Asia.

They have also been deployed on several missions in recent years to help with securing the return of Irish citizens from hostile environments, most recently in the Afghan capital Kabul after the fall of the country to the Taliban.

Two teams from the CMU took part in the response to the West African Ebola epidemic in 2014, alongside UK and Canadian military medical personnel. The following year, in November 2015, Sierra Leone was officially declared Ebola-free. Subsequently, to honour their dedication during the crisis, members of the Irish Army Medical Corps were awarded the International Service Medal by the Irish Government.

The United Nations Training School Ireland (UNTSI), which was set up in 1993, has been the focal point of the Defence Forces effort to standardise preparation for UN peace support operations.

Closer to home, during 2020 and 2021, as part of Ireland’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic, paramedics from the Army Medical Corps assisted in staffing ambulances with the HSE National Ambulance Service. They were also part of the national testing and contact tracing programme, in addition to administering vaccinations around the country.

Preparation

Overseas deployment, most often in Africa and the Middle East, can be challenging for those deployed and for

their families at home, so preparation and training for the mission is crucial, Lt Col Corcoran emphasised.

“Training actually starts off well before we even leave the country. The work that has to get done pre-deployment is essential for a successful mission. Everyone who goes overseas has to undergo a medical to ensure they’re fit for deployments.

We also make sure that they’re up to date with any vaccinations that might be outstanding or malaria prophylaxis, and so on, which might be needed for the mission.”

Once the mission begins, the doctor deals with the needs of their own unit but may be called upon to help other countries’ peacekeeping troops, as well as potentially treating civilians in emergencies.

“My routine in Syria last year would have been to run a sick parade each morning to check for any illness. We then got involved in running medical exercises, medical lectures, and medical training. But if there’s an emergency in the mission area our Quick Reaction Force could get deployed to that emergency.

Smaller observer units wouldn’t have their own in-house medical support, so they relied on us to be the medical response in case of any emergency. And we ran regular exercises to test that capability.”

Would that mean if there was a battle or other incident, you would attend to casualties on the ground? “You certainly could,” Dr Corcoran responded, before adding “but you don’t just rush in. When an incident is happening, one of the things we have to be conscious of is scene safety.

The whole idea is safety first, as I know from my own experience and from talking to military medical personnel that

have been involved in combat situations.

“They can see the casualty, but they sometimes can’t get to the casualty. There’s no point in having the doctor or the medic killed or injured because then they’re not able to help everybody else. So for example, if there was a patrol out and it came under fire, the first thing that the patrol commander does is to ensure safety and take control of the situation, as opposed to just sending in the medic straight away to a casualty if it’s not safe to do so.

“You don’t want to be down a doctor or a medic as well and then the unit is only going to suffer more. So sometimes the needs of one person can get outweighed by the needs of the unit.

“That can be quite tough to accept, especially for new military doctors. There’s the clinical thing that you want to do, but at the same time there may be constraints on you to be able to do that. The nature of the actual situation might not allow you to do carry out what you believe to be the clinical priority.

“Fortunately, I haven’t found myself in that situation because generally our missions are not at the level of combat that

would have been seen in places like Afghanistan or Iraq, but the potential is always there for something to happen.”

That was the case when Lt Col Corcoran served on one of his early missions in Liberia. “In Liberia after the civil war, the United Nations was engaged in a disarming process and one of the roles for our unit was to go on patrols of three-, fouror five-days’ duration to various villages where the disarming was happening.

“You would have groups of former rebels coming in with any amount of weapons and munitions for the UN to set up facilities for them to hand in these weapons and provide them with money and education as part of a rehabilitation process.

But what it meant was that for the day or two leading up to that, we had armed groups of former rebels congregating in the villages and that would create potential flashpoints for violence to break out again.

“We were briefed one day by one of the headquarter officers and told there was a particular rebel leader who was telling his former troops not to hand in their weapons, and this was increasing the tension in that area. As part of our patrol we were going to have to do a reconnaissance of the village and assess and report back on the situation, but to be prepared to engage with armed elements if we came under any kind of attack.

So you’re going into an area that is very sensitive. We were told ‘you know the rules of engagement – if a weapon is raised you have the right to engage and the right to defend yourself’.

“I remember during one of these patrols standing up outside the armoured ambulance at three o’clock in the morning and looking up at this fantastic starry sky. But I quickly got to realise I had a helmet and body armour on, a loaded pistol at my side, and was in an armoured ambulance as part of a patrol of armoured vehicles with heavy machine guns. Everybody was focused on carrying out this military operation with the risk of combat happening – and I’m thinking, I don’t quite remember the specific medical lecture in college that prepared me for this one!”

Job satisfaction

Lt Col Corcoran said he often looks back to that day in Dublin when military medicine piqued his interest and he is happy with the decision he made. “I’d recommend becoming a medical officer, the variety in the job, the scope of practice, the range of areas where you could be working. I’ve certainly enjoyed it. I think it’s a great experience.

I also think that there are unique experiences to be had, which doctors won’t necessarily get in other areas.Most doctors are used to working in an environment with other doctors or other healthcare professionals, but when I go for coffee or lunch I’m meeting with the transport people, the infantry people, the engineers, you’re getting immersed in so many different fields and you’re getting to talk to the people who work with your patients about the nature of their workplaces.”

Resilience is also important, he said, because the role comes with real mental and emotional challenges. “The challenges can be the simple stuff. People are far away from home. They miss the birth of their child, they miss the death of a relative, a first communion, a family wedding,” Lt Col Corcoran said.

“Being away can be challenging for people in terms of what they experience when they’re overseas and how they get to grips with that.” He speaks from personal experience as Lt Col Corcoran’s wife suffered a miscarriage last year while he was in Syria. He commended the way in which the Defence Forces facilitated him getting home for a short period, which helped him to navigate his way through the loss.

“There’s a very good esprit de corps in the military. We help each other to get through a situation. I felt that supportive spirit when I was away in Syria last year and my wife had a miscarriage. The Defence Forces was very good and I got back home for a week, which really helped. But at the same time, you continue to do the job that you have to do. If you don’t do it, you know somebody else will have to do it. So we all rely on each other to help each other.

“You put aside your own personal interests for the betterment of the unit. One of the Defence Forces’s values is selflessness, and that comes to the fore when personnel set aside personal gain to achieve their mission and can rely on their colleagues to support each other.”

Meantime, Lt Col Corcoran’s own family unit has also expanded. When MI spoke with him for this article, he and his wife had just welcomed the birth of their daughter, Hannah. In decades to come, if military medicine were to pique her interest, or that of her older siblings Lucy and Sam, their father would clearly be supportive.

“I recommend it. I think military medicine is a very interesting career for a doctor.” But he sounds a cautionary note too. “It’s not for everyone,” he stressed. “You have to be agile, you have to be able to adapt. It’s challenging, but it’s also very rewarding.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.