Prof Kevin Barry, Director of the National Surgical Training Programmes, RCSI, speaks to Catherine Reilly about his priorities and the major opportunities and challenges facing Irish surgical training

Managing the impact of Covid-19 on surgical training is a top priority for Prof Kevin Barry, the new Director of the National Surgical Training Programmes at the RCSI. In an interview with the Medical Independent last month, Prof Barry stated that the pandemic had “significantly” impacted trainees’ operative exposure. In Ireland and the UK, operative exposure had generally reduced by 30-to-50 per cent over the last 18 months.

Surgical provision has been impacted by large-scale cancellations of elective care, while it will continue to be challenged by bed capacity shortfalls and additional infection and control requirements, for example. “We have to quantify – which we are actively doing – that impact in terms of percentage and in terms of overall impact and break it down into specialties, and that is what the four Royal colleges [in the UK and Ireland] are doing at the moment… looking at the impact and ways and means of addressing that in the future,” stated Prof Barry, who is a Consultant General Surgeon at Mayo University Hospital specialising in breast cancer surgery at Galway University Hospital.

Scheduled care for benign conditions had now entered a phase of recovery, he outlined to MI in September.

“We have plateaued and are beginning to slowly see recovery. In general, the impact is a 30 to 40 to 50 per cent reduction depending on specialty. Some hospitals have been hit worse than others, and that tallies with the hospitals that have had greater numbers of Covid patients…. I think we will be dealing with that for a number of years to come. In other words, I don’t think we are going to redress that in a hurry and that is a significant issue I have to deal with.”

A particular concern for the RCSI, which President Prof Ronan O’Connell has communicated to Minister for Health Stephen Donnelly, is the need to protect training when public operative care is outsourced to private hospitals.

As Prof Barry recalled, during the first wave of Covid-19 when the public system temporarily took over private hospitals, he was enabled to bring his trainees to the private sector when undertaking breast cancer surgery. However, the need to protect training has not been recognised in ongoing outsourcing arrangements.

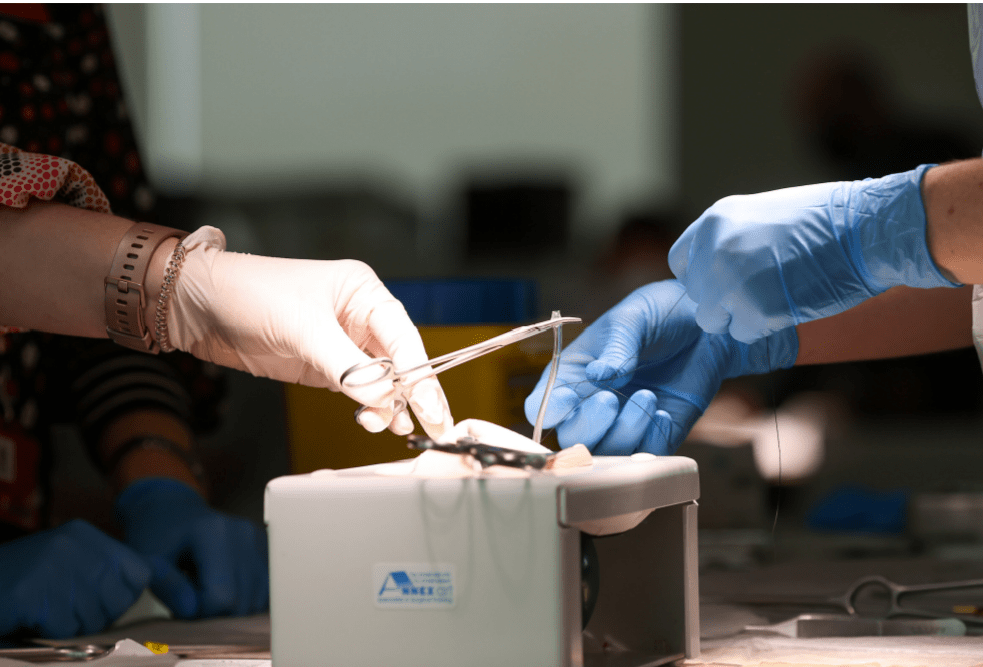

Prof Barry said that “there should be mechanisms worked out where the trainees can partake in training… [to ensure] that trainees can attend the private hospitals and scrub-in and perform, under supervision, parts of those procedures”.

He reflected that the pandemic has had “a huge impact on the way we practice and on surgical training”. Catching up on “lost opportunities” in training and service delivery will represent a major challenge for the foreseeable future.

“We have an awful lot of work ahead of us,” stated Prof Barry, who will maintain a 50 per cent commitment to clinical practice while in his RCSI role.

New curriculum

The introduction of a new surgical training curriculum is the second key focus for Prof Barry. The curriculum, which has been agreed by the four Royal colleges, came into effect in August. “It is not a radical departure from what we were doing, but what it does emphasise is the greater need for surgeons to be generally trained,” explained Prof Barry.

The new curriculum emphasises generalisation “early on” in training as well as significant exposure to emergency surgical practice.

Prof Barry added: “The majority of our workload has to do with benign, non-malignant disease and emergency

surgery, and a lot of surgical trainees are very interested obviously in having a little specialisation component to

their training, but not at the expense of diluting their exposure to the more common conditions we have to deal

with on a day-to-day basis.”

It is not a radical

departure from what

we were doing, but

what it does emphasise

is the greater need

for surgeons to

be generally trained

He envisaged the curriculum would be helpful in improving availability of surgical provision, particularly in recruiting surgeons in model three hospitals. It is also relevant in the context of plans to employ surgeons within regional networks, stated Prof Barry.

In the UK, some newly-qualified surgeons have needed additional training to handle emergency surgical take, noted Prof Barry. However, he did not consider this was a problem in Ireland. Asked why Irish trainees may be emerging more proficient in this regard, Prof Barry said the standard of surgical training in Ireland was “consistently high”.

“This reflects a cohort of highly motivated and competitive surgical trainees who receive strong clinical support

and mentorship from their consultant trainers,” according to Prof Barry. He said there were also “robust systems” in place to monitor trainee performance and identify trainees who required extra support, including additional training time where necessary to reach agreed training outcomes.

It is “extremely unusual” for a higher surgical trainee to exit any of the surgical training programmes. “This probably reflects the close-knit nature of the surgical community at both consultant and trainee level,” commented Prof Barry. He added that the calendar of national surgical meetings helps to foster good working relationships as there is “a strong tradition” in Irish surgery of trainees being encouraged by their trainers to present both clinical and laboratory-based research at various meetings.

“The exam performance by our surgical trainees at the end of training also reflects the very high standard

of training in this country. I can testify to this in my role as an Intercollegiate Examiner since 2007.”

Competency-based

Another important aspect of the new curriculum is that it involves competency-based training.

“What we mean by competency-based training is that we are, to some extent, moving away from the idea that you have to have so many of a certain procedure performed in order to be signed-off. Competency-based training means if we believe you are competent at performing something, that we accept you are now able to perform such an operation and you move on from there.”

It facilitates trainees in many ways, said Prof Barry. For example, there is a “certain amount of variation” in the

number of cases a trainee gets to perform in one hospital versus another, which is not under the control of the

trainee or their consultant trainer. “The idea going forward is once you achieve a standard of competency, we are happy with that as a training programme or body.”

Prof Kevin Barry

There is also the potential in the future for trainees to finish their training programmes ahead of schedule once they meet the requirements.

Prof Barry continued: “The assessment processes we are introducing with the new curriculum are competency-based and will help trainees going forward. Part of that assessment will be a multiple consultant report, which is where you will be assessed by a greater number of consultants within an individual hospital, so you will get a more holistic assessment of a trainee’s performance.”

Training expansion

A third major priority for Prof Barry involves expansion of the surgical training programmes. Currently there are 383 surgical trainees and it is envisaged the number will have reached 520 by 2028. “Sláintecare envisages significant expansion in the consultant workforce long-term and NDTP [National Doctors Training and Planning] have flagged that and said to all of the training bodies, ‘you need to increase your training numbers so we have enough consultants in the system to apply for jobs as they come up.’”

“We have laid out a roadmap for this. In July this year, the RCSI have increased the number of trainees who are commencing core surgical training with a view towards kickstarting that process.”

This year the number of doctors entering core surgical training increased from 60 to 80. In 2023, it is envisaged approximately 60 of these trainees will enter higher surgical training, taking into account attrition between core and higher training.

Overarching matters

Prof Barry identified three overarching challenges and opportunities for the coming period – Sláintecare, which he noted as the subject of ongoing controversy; the trauma strategy; and the Covid-19 pandemic.

The model of care envisaged by Sláintecare would involve network arrangements within Hospital Groups, stated Prof Barry. He said it was “very important” these networks were set up in such a way to ensure equitable distribution of surgical expertise across the country, especially in the context of an aging and expanding population.

He further observed that, going forward, many model three hospitals will be designated as trauma units under the national trauma strategy, which means they must have 24-hour accident and emergency cover, emergency general surgery, and orthopaedic surgery cover.

“In the future, a lot of consultant opportunities in terms of expansion of hospital consultant numbers, I think will take place along the lines of the trauma strategy as well, particularly if you look at general surgery, orthopaedics – they will be two critical specialties in model three hospitals.”

Prof Barry feels that his own professional background was pertinent to his appointment as Director, in the context of future surgical needs and potential working arrangements.

“My working life is very much based on general surgery and emergency general surgery. I do that component of my work in Castlebar in Mayo University Hospital. My workload in Galway is with the symptomatic breast unit where I function as part of the breast surgery team and National Cancer Control Programme, so I have a specialty interest, which takes me to Galway one day per week.”

Facilitating surgeons in having sessional commitments between model three and model four hospitals will assist in recruitment to the former, he believed.

However, on-call rotas in model three hospitals “will have to be brought up to a more acceptable level and I would specifically say maybe a one-in-five or a one-in-six on-call consultant rota would be something that would need to be looked at long-term….

“I have been on a one-in-three rota for the past 22 years and that is because I don’t know any better. To me that is normal and when I say that is normal, it is obviously not normal, but it is the sort of lifestyle and professional career I have been accustomed to. I know it’s not right, but I don’t complain about it, I just get on with it. But I know that going forward, that kind of a rota acts as a very strong disincentive to recruit surgeons to replace the likes of me.”

Recruitment to model three hospitals would also be aided by further opportunities for surgeons to become involved in both undergraduate and postgraduate training.

Prof Barry referenced the academies established by NUI Galway School of Medicine in Saolta’s model three hospitals as a positive example in this regard.

Working hours

Asked whether cohorts of surgical trainees worked excessive hours, Prof Barry said: “We have to be compliant with the European Working Time Directive (EWTD) and I would say most surgical trainees are on a one-in-five or one-in-six rota. I think a one-in-five or one-in-six rota is a reasonable rota because you have to have the exposure to emergency surgery and that is a significant component of our training programmes.”

Prof Barry clarified that he believed the actual hours worked were “largely” compliant with the EWTD. Ensuring trainees have time for personal and family life is “obviously a big area”, he acknowledged.

He said over the past seven-to-10 years, there has been greater interest and participation by female candidates in surgical training. Currently, around 40 per cent of surgical trainees are female. Prof Barry referenced the Progress

report, produced by an RCSI working group led by Prof Deborah McNamara, which has examined ways of encouraging a more equitable gender distribution in surgical training. An update on its recommendations has also been published.

“The idea of surgical training being a male dominated profession, that is pretty radically changing,” he added.

According to Prof Barry, taking time out of training for personal or family reasons is not a problem. He said where trainees wish to take extended leave, it is discussed in confidence with the Director of the relevant surgical training programme, while maternity leave is a statutory entitlement. The commonest non-personal reason for taking time out is to do research.

While there is a national flexible training scheme, Prof Barry said the surgical programmes receive “very, very few requests” for flexible or less than full-time training. Nevertheless, the “option is always there and is always given to them”. However, does the low number of requests for flexible training suggest some trainees are concerned it could affect their careers?

“Not in the slightest,” said Prof Barry, who described the trainees as “highly competitive individuals” for whom peer pressure may be a factor. He said trainees were neither penalised nor discouraged from taking time out of training.

Bullying and undermining of trainees (across specialties) has been identified in Medical Council research as a significant problem. According to the Council’s most recent Your Training Count report, which collected data in 2017, some 41 per cent of trainee respondents experienced some form of bullying or harassment in their roles.

Prior to his current position, Prof Barry was National Training Programme Director for General Surgery. In that capacity, such incidents came to his attention “very, very rarely”. “I would have dealt with two or three incidents,” he confirmed. However, Prof Barry noted that “globally bullying and harassment is something that happens frequently” and also referenced the evidence from the Council’s Your Training Counts surveys. “But in terms of reporting it, we can only deal with it when it comes to our attention, but there are mechanisms by which it is dealt with if it is reported to us.”

Prof Barry acknowledged that it may be “very difficult” for a trainee to feel confident in reporting these types of issues.

“I have no ways or means of knowing if bullying or harassment is going on unless it is brought to my attention. But

if it gets to our attention, we deal with it in confidence.”

Another matter identified by the Medical Council during its training programme inspections has been lack of protected trainer time. “It certainly has,” agreed Prof Barry. “What the RCSI has done over the last year in particular is to establish a Faculty of Surgical Trainers,” he continued. “Going forward, the RCSI has emphasised to the Department of Health that there should be protected time for consultants when it comes to training trainees…. As far as the RCSI is concerned, we would like to see protected time in place for consultants.

“I know that is going to be part of the Sláintecare consultant contract negotiations. I am not involved in that at all, but I know the IMO and the IHCA are going to be pressing for that.”

According to Prof Barry, the Faculty of Surgical Trainers is a means for greater engagement with consultant trainers, of whom there are about 550.

Surveys have identified their three top priorities as ensuring identification and management of a trainee in difficulty; balancing the needs of service delivery with education; and giving effective feedback to trainees

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.