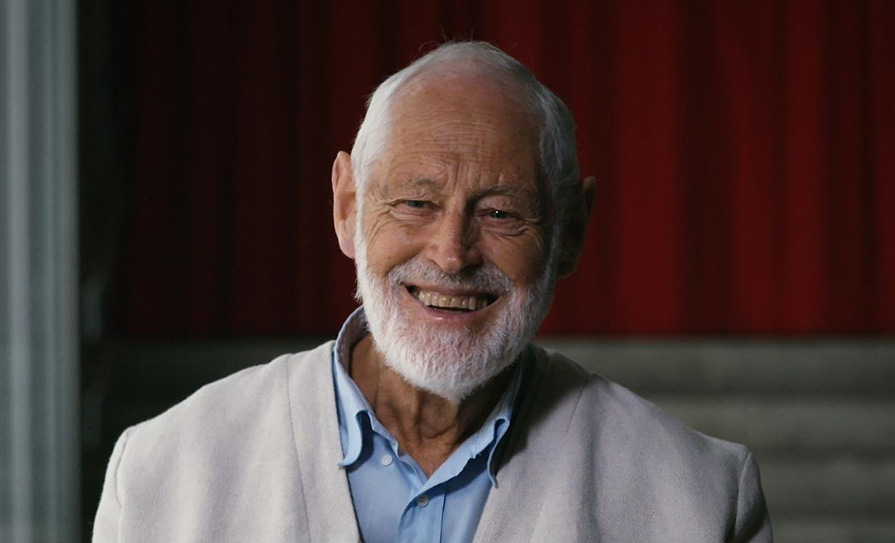

Dr James Lucas, Medico-legal Consultant at Medical Protection, explains the common dilemmas faced by doctors when deciding to disclose their patients’ medical records to another person or body

Dilemma 1

My patient has become a ward of court due to mental incapacity, after being diagnosed with an acquired brain injury following a fall. The court appointed the patient’s daughter to manage his affairs. Can I disclose the patient’s medical records to his daughter if she asks for them?

When a person is deemed to be incapable of managing their own affairs and the matter is brought before the courts, the High Court judge normally appoints a “committee of the ward”. Despite the name, this is usually one person and often a family member who may be given certain powers to make decisions in relation to the property and money of the ward.

In this instance, the patient’s daughter is also expected to oversee the personal welfare of the ward from day to day. In addition, the registrar of the wards of court can ask the daughter to report back on issues about her father’s residence, physical and mental condition, maintenance, comfort and such other matters that they may wish to be informed of.

If the patient’s daughter is seeking information as a committee of the ward, it would be reasonable for the doctor to disclose relevant medical information about her father, thus allowing her to fulfil her legal obligations. This is consistent with the Medical Council’s advice to doctors: “If the patient lacks capacity to give consent and is unlikely to regain capacity, you should consider making a disclosure if it is in the patient’s best interests.”

It is important to remember that the patient’s daughter as a committee of the ward, does not have unfettered rights of access to medical information pertaining to her father. For example, past medical history that is unrelated to the patient’s current condition would be irrelevant information.

In this instance, the doctor should ask the patient’s daughter to explain why the information is needed. The justification of any information disclosure should then be recorded in the patient’s medical records.

The law in relation to capacity is set to change. Once the Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act 2015 is fully implemented, each ward of court will be reviewed in accordance with the new system. In future, a ward who has regained their mental capacity will be discharged from wardship. A ward who continues to have capacity needs will be discharged from wardship and offered the support option most appropriate to their needs.

Until the law changes, the committee of the ward, or the patient’s daughter in this context, will retain delegated authority to oversee the welfare of the ward on a day-to-day basis in accordance with the order of the court.

As a general rule, doctors working in hospital settings should consult their data protection team before disclosing records outside of their organisation.

Dilemma 2

Should a doctor disclose a patient’s information against their wishes to prevent harm to another person?

Confidentiality is central to the trust between patients and healthcare professionals. Patients must be confident that intimate details about their health and personal relationships go no further than the consultation room. The duty to maintain patient confidentiality is rooted in medical ethics, common law and in contract law. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) also imposes obligations in terms of the lawful processing of personal data.

But the duty of confidentiality is not absolute. A judge, by law, may require doctors to disclose their patient’s confidential medical information in the context of civil litigation, criminal or family proceedings. In rare cases, where patient consent has not been obtained, or where a patient has refused consent, disclosure of confidential medical information may be justified in the public interest, to protect others – for example, from the risk of death.

Case study

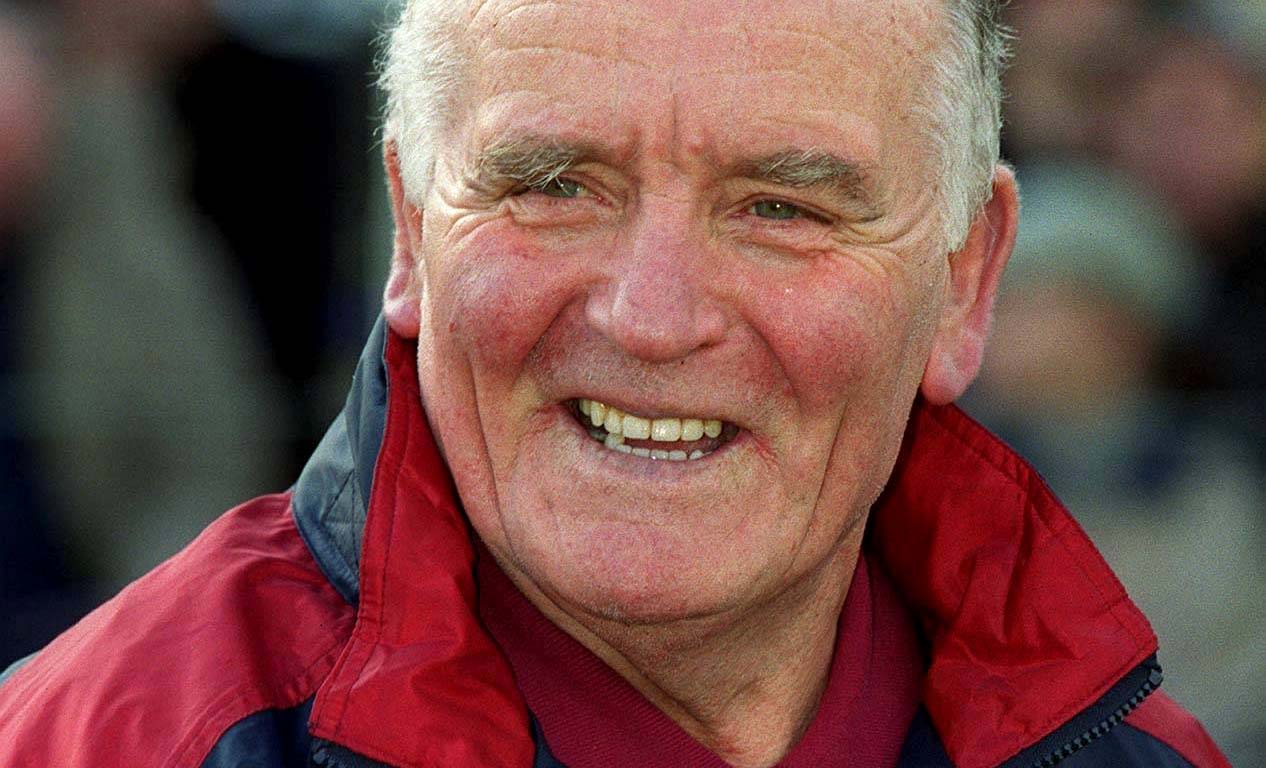

Last year, the High Court decided that a 17-year-old boy’s HIV status was not to be revealed to a close female friend. ‘A’, the teenage boy, had been diagnosed with HIV infection at birth and was in the statutory care of the Child and Family Agency (CFA). He was described by the Court as an intelligent and capable person, but there was evidence he had significant behavioural issues in the past.

One of his closest friends, ‘B’, was a 17-year-old girl. A denied that B was his girlfriend and he denied that they had ever had sexual intercourse. However, the CFA was of the view that despite A’s denials, the teenagers were sexual partners and were not using condoms.

The CFA sought a declaration from the High Court that it was lawful for them to disclose the fact of A’s HIV status to B so that she would have the opportunity of undertaking medical tests, treatment and counselling if necessary, despite A’s refusal to consent to the disclosure of his HIV status.

The Court’s analysis

The Court considered a range of issues including the circumstances of the relationship between the teenagers, the failure by A to take his antiretroviral drugs as directed during a three-month period and whether, or not, A would use condoms if he was having intercourse with B. There was also expert medical evidence on the risk of B contracting HIV if they were having unprotected sex, and the effect of disclosure on A’s mental health, if his HIV status was disclosed to B.

While the Court had little hesitation in finding that there was a possibility that A was having sexual intercourse with B, the judge concluded that the CFA had not proven, on the balance of probabilities, that there was such a relationship. The Court indicated that even if this analysis was incorrect, A would not put B at risk by having unprotected sex with her. Hence, the Court concluded that there was no basis for the breach of patient confidentiality.

Issues to consider as a doctor

The CFA initiated court proceedings on this occasion, however, deciding whether to breach confidentiality in the public interest can just as easily fall on the shoulders of an individual medical practitioner. The dilemma can arise irrespective of the patient’s age.

In the context of his commentary on the case, the judge took the opportunity to examine the broader issues, namely in what circumstances can a doctor breach his or her duty of confidentiality in the public interest. These can be considered under the following headings:

1) The legal test

The Court determined that the appropriate test to apply to ascertain whether patient confidentiality should be breached is whether “on the balance of probabilities, the failure to breach patient confidentiality creates a significant risk of death or very serious harm to an innocent third party”.

In this scenario, A’s privacy was not the only issue to weigh in the balance. There was also the interest of B who was potentially at risk of harm and the public’s expectation with regards to having a confidential medical service.

2) Whether HIV infection is a ‘very serious harm’

Although HIV is a significant condition, the Court determined that contracting HIV is no longer a terminal one but rather a chronic and lifelong condition that can be managed. Accordingly, HIV infection is not a ‘very serious harm’ to justify a breach of patient confidentiality. Furthermore, the Court held that the risk of contracting HIV through sexual intercourse is low and can be further reduced through the use of condoms.

3) Doctor-patient relationship and societal factors

The Court recognised that the doctors looking after A were well-intentioned and had the interests of B at heart. But if an order was granted giving doctors the right to breach confidentiality where a patient has a sexually transmissible disease, that ‘right’ would become a responsibility for doctors in future. Such responsibility could carry liability for those healthcare professionals who failed to breach patient confidentiality, where that failure results in harm to a third party.

Additionally, the Court held that there was a public interest in patients remaining open and frank with their doctors. If the CFA had been successful in this case, it would work as a disincentive to patients with sexually transmissible diseases from seeking medical advice. Such persons would perceive that there would be a risk that their doctor would disclose this fact to their alleged sexual partners, if the patient refused to do so.

The Court concluded that this would be detrimental to society as a whole, since it could lead to patients with communicable diseases failing to seek medical advice, which could result in those diseases not being treated and becoming more prevalent in the community.

In a nutshell

If there is a significant risk of death to a member of the public, a doctor would not only be entitled to breach confidentiality, but it seems clear that they would have a duty to act to try to prevent innocent deaths.

Where there is no risk of death to a member of the public but a significant risk of “very serious harm” remains, the public interest takes precedence over the interest of a patient in keeping medical information confidential. It also takes precedence over the public expectation that doctors keep patients’ medical information confidential. However, in the case of A and B, the test had not been met and it would therefore not be lawful to breach A’s confidentiality.

Disclosures of information in a patient’s medical record in the public interest can be ethically challenging, so do not hesitate to consult your medical defence organisation for advice.

Tips for doctors

• Ensure that a clear record explaining the decision is made in the patient’s records (including cases where there is a decision to maintain confidentiality).

• When disclosing information in the public interest, you should normally inform the patient about the disclosure.

• Any disclosures that are made should be to an appropriate person or body, and include only the information needed to meet the purpose.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.