Dr Rachael Comer, Education And Training Manager, Screening Training Unit, Cervicalcheck; Dr Nóirín Russell, Clinical Director, Cervicalcheck; Dr Sarah Fitzgibbon, Primary Care Clinical Advisor, Cervicalcheck; Dr Laura Heavey, Specialist In Public Health Medicine; And Ms Grainne Gleeson, Programme Manager, Cervicalcheck.

CervicalCheck offers free cervical screening to women and people with a cervix aged 25- to-65 years. The upper age limit changed from 60-to-65 years in April 2020 in line with the recommendations of the HIQA Health Technology Assessment carried out in 2017. This ensured that women who had turned 50 when the screening programme first began in 2008 would be eligible for at least one HPV test before exiting the programme. However, recent research carried out by the National Screening Service revealed that women aged over 50 have the lowest screening uptake, with one-in-four women in this age group not attending for screening.

What is cancer screening?

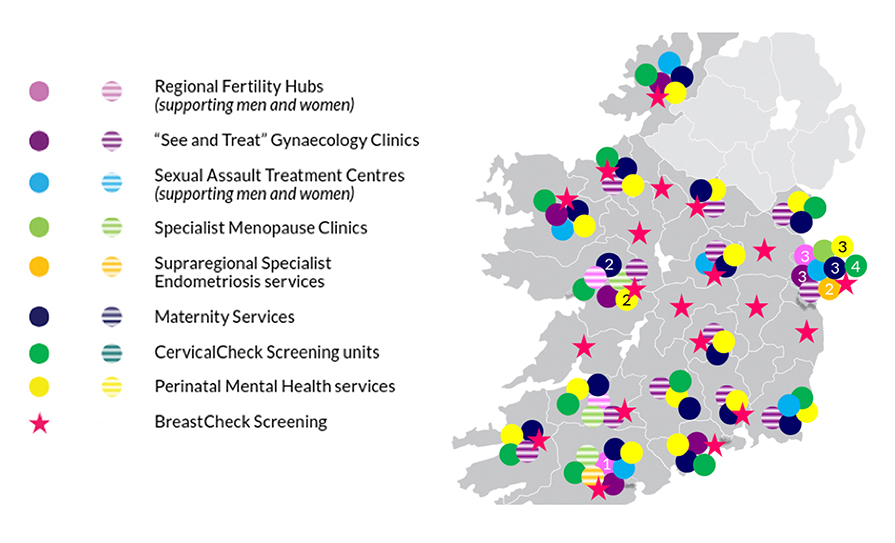

The purpose of cancer screening is to detect pre-cancer or early-stage cancer in asymptomatic individuals, so that timely diagnosis and early treatment can be offered. Ireland has four quality-assured, organised, population-based screening programmes under the management of the National Screening Service – BreastCheck, CervicalCheck, BowelScreen, and Diabetic RetinaScreen. Since the introduction of CervicalCheck, the incidence of cervical cancer and its mortality rate has declined during the period 1994-2018. Cervical screening can save lives, decrease morbidity, improve quality-of-life, and deliver reassurance to individuals about their health.

HPV infection and cervical cancer

The vast majority of cervical cancers are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV). This aetiology provides an opportunity for the global elimination of this disease, which disproportionately affects young under-educated women in low- to middle-income (LMI) countries. In fact, the death rate from cervical cancer is three times higher in LMI countries than in high-income countries like Ireland. Genital HPV is easily spread through sexual skin-to-skin contact. Infections are very common, with the incidence peaking between 18 and 30 years of age. There are 14 high-risk types of HPV, with types 16 and 18 causing over 70 per cent of cervical cancers. About 80 per cent of sexually active adults have been infected with one or more genital HPV strains at one time or another, but are unaware of the infection because HPV is usually spontaneously cleared by the body’s immune system. It is estimated that more than 90 per cent of women clear the infection spontaneously. However, a small percentage of women do not clear the infection and it can remain dormant or persistent, sometimes for many years.

There are two main types of cervical cancer; squamous cell carcinoma (77 per cent of cases) and adenocarcinoma (18 per cent). The remaining 5 per cent of cervical cancers are due to rarer histological types. It is now recognised that persistent HPV infection causes at least 92 per cent of cervical cancer in total and is responsible for 99 per cent of squamous cell cancers. Therefore, cervical screening with HPV and reflex cytology is more effective at reducing the risk of squamous cell carcinoma than other histological cancer types. Adenocarcinoma of the cervix is a more aggressive type of cancer associated with a poorer prognosis. Cervical screening programmes internationally have had less impact on reducing adenocarcinoma than squamous cell carcinoma as adenocarcinoma cells typically develop within the endocervical canal, which may not be able to be sampled during the screening test.

CERVICAL CANCER IN IRELAND (ANNUAL)

- Over 6,500 women need hospital treatment for pre-cancer of the cervix (CIN)

- Approximately 300 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer

- Approximately 90 women die from cervical cancer

Figure 1: Prevalence of pre-cancer and cancer of cervix in Ireland (www.HSE/HPVaccine.ie)

Cervical cancer elimination

Cervical cancer is preventable and curable, as long as it is detected early and managed effectively. There are two approaches to preventing cervical cancer: Primary prevention through HPV vaccination, and secondary prevention through effective screening and treatment programmes.

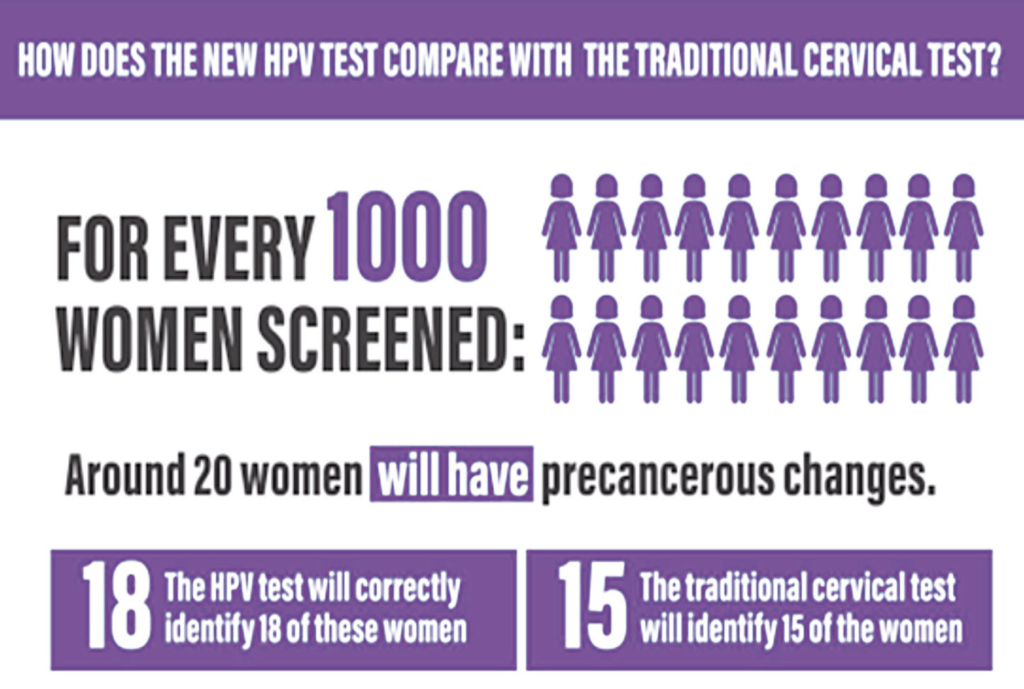

HPV testing was introduced as the primary cervical screening test in Ireland in March 2020. This is in keeping with other high-income countries such as Australia, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, and the UK. In 2017 a Cochrane review of 40 studies concluded that if 20 women out of 1,000 had precancerous changes, primary HPV screening would correctly identify 18 of these women, whereas primary cytology screening would only identify 15 of these women. HPV as a primary screening test, followed by reflex cytology in those that screen positive, will detect 90 per cent of women at risk of cervical cancer. This is significantly better than testing with a cytology-first test, which detects 75 per cent of women at risk.

The roles of CervicalCheck and primary care

CervicalCheck maintains a register of eligible women, calls and recalls them at predetermined intervals, and works with affiliate laboratories and colposcopy units to deliver the appropriate results and management recommendation for each screening test. It is important to understand that the overall clinical governance for each woman remains with the clinicians involved, either in primary care or colposcopy. Collaboration between the administrative call-recall team, primary care sampletakers, cytology laboratories, colposcopy clinics, and histology laboratories is essential in order to provide a quality-assured screening programme.

In primary care, over 65 per cent of cervical screening samples are taken by practice nurses. Sampletakers have a powerful role in making the cervical screening programme a success. Research shows that GPs and general practice nurses (GPNs) remain the most trusted source of information for most women. The relationship that develops between a woman and her primary care clinician can make the screening process clearer and less overwhelming, and ultimately increase the participation of more women. GPs and GPNs are particularly well placed to reach out to under-served communities where screening rates can be low and incidence rates high, resulting in increased health inequities.

Screening coverage

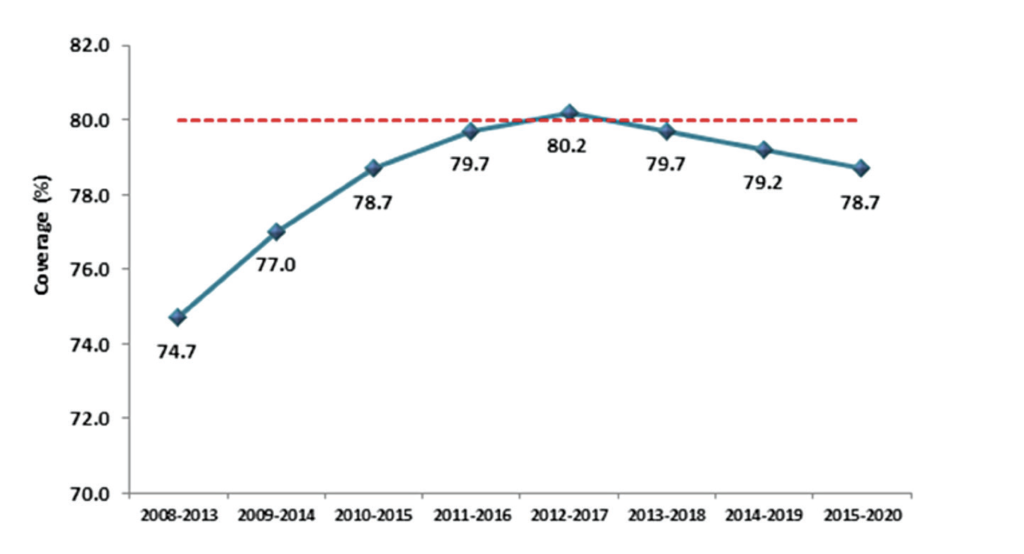

Screening coverage is defined as the proportion of individuals of the eligible population screened that has engaged in screening within a specific period, and directly correlates to the effectiveness of a screening programme. In keeping with the principles of screening, all screening programmes need to achieve high target coverage to be effective. CervicalCheck’s objective is to achieve at least 80 per cent population coverage during a five-year period. Figure 3 shows the five-year rolling averages since 2008, with a peak of 80 per cent in 2012-2017. Due to Covid-19 restrictions and public health advice, CervicalCheck paused cervical screening in primary care from March to July in 2020. This led to a decrease in the number of women screened in 2020, but despite Covid-19 still being prevalent in our country in 2021, cervical screening testing in primary care exceeded projected targets by 14 per cent. Population coverage for cervical screening in Ireland compares favourably with adjacent countries. In England, cervical screening coverage has fallen to a 20-year low at just 70 per cent and coverage in the Netherlands is just 57 per cent.

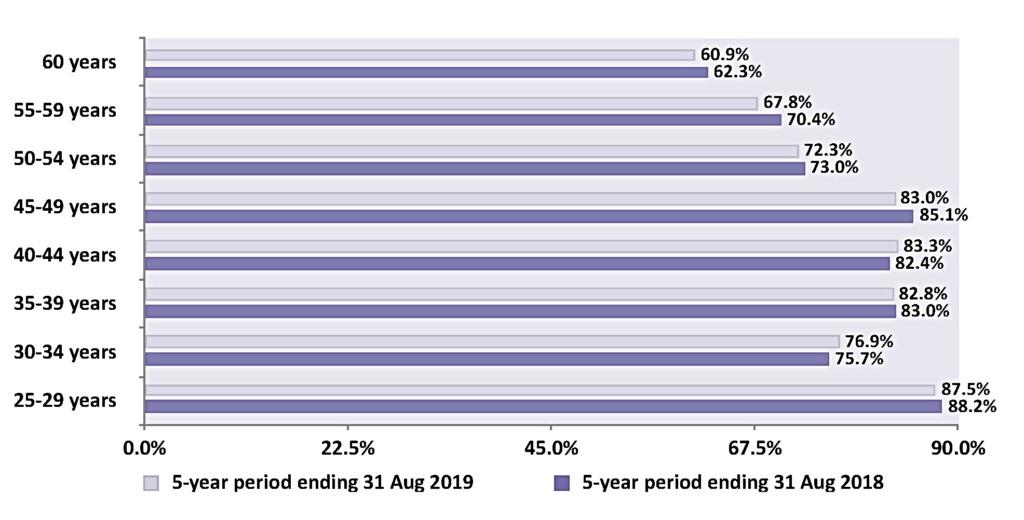

Figure 4 shows the five-year coverage of eligible women by age group on the cervical screening register in Ireland and highlights that the 80 per cent standard for coverage was met in four of the eight five-year age bands. Consistently over the period of this report, younger participants (aged 25-to-29 years) have the highest coverage. It is worth noting that England, Australia, Canada, Sweden, Norway, France, and Italy have all documented that young women, particularly 25-to-30-year-olds, are the poorest attendees. Conversely, in Ireland, coverage is lowest in the 60+ age group, at just 60 per cent. In March 2020, CervicalCheck increased the age limit from 60-to-65 years alongside the change to a primary HPV programme. This unfortunately coincided with the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic and those in the older age groups in society were advised to restrict their movements for many months, meaning very few of those women would have attended for screening until absolutely sure it was safe to do so.

Women over 50 years are a high-risk group

For women in the pre-HPV vaccine cohort (ie, those born before 1997 in Ireland), participation in cervical screening is their predominant means of preventing cervical cancer. Inadequate screening participation at age 50-to-64 years has been identified as a significant risk factor for cervical cancer for women in their 60s and 70s in a population-based case control study examining the risk of developing cervical cancer in women aged 65-to-83 years. The study concluded that women are six times more likely to develop cervical cancer if not screened between the ages of 50 and 64. If adequately screened, screening protection was greatest from 65-to- 69 years and decreased progressively since their last normal cytology test. Therefore, it is extremely important that women over 50 years engage with the cervical screening programme, as this will reduce their risk of developing cervical cancer and its associated mortality and morbidity in later life.

Why are women over 50 years not attending?

Numerous research studies have reported that women over 50 have multiple barriers to attending cervical screening. Overall, knowledge about both screening and HPV infection was poor. Women associated HPV with sexual transmission, which caused feelings of embarrassment and unease with their own bodies and their sexuality. Fear that something was wrong was also identified as a deterrent towards screening. Pain and embarrassment during the procedure were noted at higher levels in older women. A recent survey conducted on behalf of the HSE stated women were also concerned about attending their screening appointment due to Covid-19.

What can sampletakers do to make a difference?

- Give information tailored to the needs of women over 50: Figure 5 ‘Having the conversation’ highlights the information that women need to make an informed choice about participating in cervical screening. It is important to use open language and normalise HPV’s relationship to sexual activity. You can remind the woman that HPV can be picked up through any kind of sexual contact with anyone, even if the sexual activity was years ago.

- Actively encourage participation in screening: Sampletakers need to actively remind women to use the ‘check the register’ function on the CervicalCheck website. Sampletakers can also do a database search of all women born after 29/03/1959 who are aged between 25 and 65 years – these women are in the eligible age range (remember to confirm eligibility through the website, as they may have had screening done elsewhere).

- Make every contact count: Consultations related to screening may not arise in a woman’s routine interactions with their GP or GPN, but sampletakers need to have the conversation on both the benefits and limitations in this high-risk age group. Studies have identified that women who presented to the GP with gynaecological conditions, such as menorrhagia or menopausal symptoms in the last five years were all up to date with screening. This indicates that consultations specific to gynaecological problems prompt both the clinician and the patient to consider cervical screening. However, screening is for people who are asymptomatic, and it is very important that it is not necessarily tied to conversations about genito-urinary symptoms, as this may lead women over 50 to believe that if all is well ‘down there’, that they do not need to attend for cervical screening.

Open the conversation

Conversely, bringing up the topic of cervical screening may allow women to voice concerns about their sexual health that they may otherwise have kept to themselves. The genito-urinary symptoms of menopause (GSM), such as daily discomfort, itch, pain, and recurrent UTIs can cause significant physical and psychological distress, and yet women often feel uncomfortable about speaking to their doctor or nurse about them. Introducing the topic through discussion of cervical screening, and addressing concerns about fears of pain or discomfort in passing a speculum can provide the opportunity for offering appropriate and potentially life-changing management of these symptoms.

HAVING THE CONVERSATION – A SAMPLETAKER’S GUIDE NOR– MALISING HPV INFECTION AND TESTING FOR WOMEN OVER 50

- Highlight the purpose of cervical screening: Differentiate between screening and diagnostic tests.

- Emphasise benefits of screening: screening saves lives, it identifies HPV before it causes cancer and helps identify abnormal cell changes when they are easier to treat.

- Explain limitations of screening: it does not prevent all cases of cervical cancer, as cervical cancer can develop in between screening tests, which is why symptoms should never be ignored.

- Explain the risk factors for cervical cancer: smoking, early age at first intercourse, persistent HPV infection.

- Normalise HPV infection by making women aware that even being with one partner means that they still have an 80 per cent chance of contracting HPV infection, and emphasise the ability of HPV infection to lie dormant for many years (this means that previous screening tests may have been normal).

- Reassure that most people’s immune system clears HPV from their body within 18 months without any treatment. For some people the infection remains and this is why a repeat test in 12 months will check if the infection has gone.

- Explain that in the absence of persistent HPV, it is safe to repeat the next screening test in five years. Without HPV infection, abnormal cells typically return to normal without intervention.

- Explain that if testing detects persistent HPV infection, referral to colposcopy is initiated. This does not mean that you have cancer but means the colposcopy procedure will identify abnormal cell changes when it is easier to treat.

- Emphasise that regular screening between age 25 and 65 years has a protective effect even after a woman completes cervical screening.

Figure 5: Having the conversation

Practical advice

After menopause the vagina may be dry and atrophic, making introduction of the speculum more difficult. Choose an appropriate sized speculum and apply a water-soluble lubricant to the middle third of the shaft of the speculum (do not apply lubricant to the tip of the speculum as this can interfere with lab analysis). Remember one bad sample-taking experience can become a deterrent for a woman to return, so ensuring her comfort throughout the procedure is of paramount importance. If it is apparent from the initial consultation that she has symptoms related to vaginal atrophy, then a course of vaginal oestrogen should be offered.

The duration of the course is dependent on the severity of the symptoms, but a good rule of thumb would be to prescribe a pessary such as Vagifem or Vagirux twice weekly for six weeks, stopping five-to-seven days before the test is due in order to ensure that no trace of the pessary remains at the time of the test as it could interfere with the laboratory analysis. If the symptoms are very severe, it may be possible to continue with an oestrogen gel, such as Ovestin up to two days before the test is due.

Note: Previous breast cancer is not a contraindication to vaginal oestrogen in the vast majority of cases.

Unsatisfactory results

The cervical cell yield from the cervical screening test may be scanty. The absence of oestrogen causes the squamo-columnar junction (SCJ) to invert into the endocervical canal, making it more difficult to harvest cells from the columnar epithelium and transformation zone (TZ). If a cytology test is warranted, this leads to a higher probability of an unsatisfactory result. If a test needs to be repeated due to inadequacy, it is recommended to use local oestrogen PV as described above to encourage eversion of the SCJ, so that both the columnar epithelium and the entire transformation can be sampled.

Non-binary and trans people with a cervix have significantly lower screening rates than the general population. Sampletakers need to use inclusive language and indicate LGBT+ friendliness in the practice through the use of inclusive posters and behaviours. All practice staff should be encouraged to complete the HSELanD training modules and access the CervicalCheck quick reference guide for LGBT+ screening when available.

Refresh your information resources

Waiting rooms are now open again so this is a good time to refresh practice posters and information. You can access posters and other promotional materials at www. healthpromotion.ie for your waiting area.

HPV self-testing – an option for the future?

HPV self-testing may become an alternative option for women who, for whatever reason, find it difficult to engage with a traditional clinic-based approach to cervical screening. The Netherlands is currently the only country in western Europe that offers self-sampling to all women who request it. Uptake of self-sampling there remained as low as 20 per cent throughout the pandemic, indicating that it has not been widely accepted by women despite its apparent convenience.

Several countries, such as France and Denmark, offer self-sampling to certain under-screened populations. There are also ongoing pilots in the UK to assess this new method of screening. Further investigation within an Irish context is needed to assess if women would be willing to use this tool and to consider how it should be offered if implemented within our Irish cervical screening programme. There are many advantages to the woman of attending in person and having a holistic consultation around the benefits and limitations of screening with a well-trained clinician.

Conclusion

The forward-thinking implementation of the schools-based HPV vaccination programme along with the HPV primary screening programme puts Ireland ahead of many other countries and in a great position to aim for elimination of cervical cancer. We are fortunate to be in this position when we consider the global burden of this disease. However, we do know that older women are under-served and at increased risk and so we must increase our efforts to ensure that cervical screening is accessible, acceptable, and available for everyone who would benefit from it.

References on request

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.