There is a common generalisation that men live shorter, but healthier lives, and women live longer lives, but in worse health. Although this is certainly an oversimplification, there are notable sex differences across certain dimensions of health.1 Some of the causes of sex differences in health and mortality are biological, innate, or related to differences in genetics and hormones. A recent review1 indicates that there is a higher occurrence of more lethal conditions among men (heart disease, stroke, diabetes), whereas women have more disabling chronic conditions (for example, arthritis, depression). Women’s health includes issues that impact women in a different way to men, such as heart disease and diabetes, but also issues unique to women, including gynaecological and reproductive health.2 Here, we focus on some of the common conditions for which women seek advice in primary care.

Menorrhagia

Menorrhagia (heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB)) is the loss of over 60-to-80ml of blood per cycle compared to an average of 30-to-40ml. As this is impractical to measure, an assessment is made based on patient information. These women may describe having to use both tampons and sanitary towels, and very frequent changes of such, which can negatively impact daily activities.3 Women with HMB are often found to have a disturbance in the endometrial coagulation process, or increased vasodilatory prostaglandin secretion vs vasoconstrictory PG secretion. There is no identifiable cause in >50 per cent of cases, but in some women, HMB can be a result of underlying disorders.

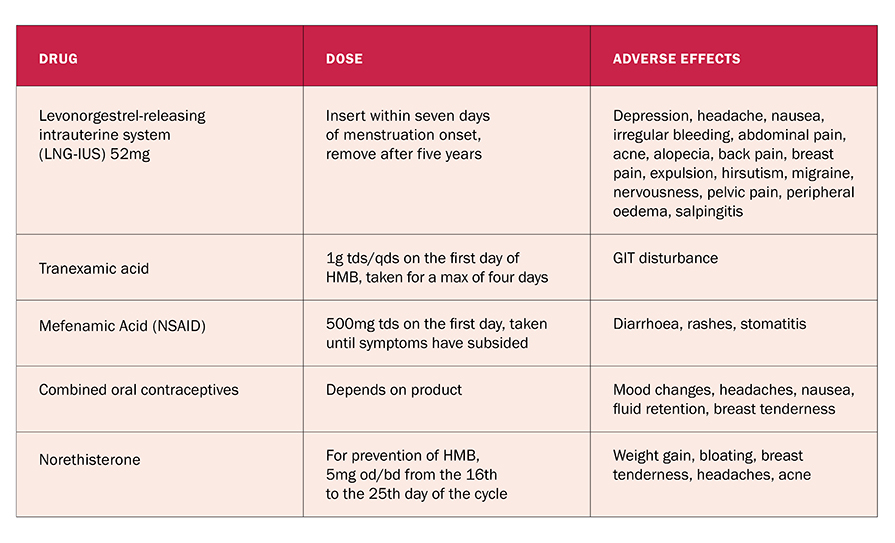

A detailed medical history is the best way to diagnose HMB, with physical examinations and tests where needed to exclude more serious conditions. NICE defines HMB holistically as “excessive blood loss that interferes with the woman’s physical, emotional, social and material quality-of-life”. The rate of HMB increases with age, with 25 per cent of women aged 30-to-50 years affected. In the UK, 20 per cent of referrals to specialist gynaecological services are for HMB. Table 1 describes recommended treatments for HMB, although OTC analgesics can also be useful for pain.

TABLE 1: Pharmacological treatments for heavy menstrual bleeding3,4

Thrush

Candida is a yeast that is commonly found in the vagina as part of normal flora. It can change from being a commensal organism to a pathogenic one, causing symptoms of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC, commonly named thrush). Most cases are caused by Candida albicans, however, less-common candidal species such as Candida glabrata may be implicated in recurrent cases.5 It is estimated that uncomplicated VVC affects up to 75 per cent of women. Predisposing factors include the use of antibiotics, HRT, pregnancy, diabetes, genetic factors, and behavioural factors.

Candida can lead to vulvar discomfort, itch, and vaginal discharge in women; balanitis and itch in men.6 Diagnosis is made based on description and appearance. This can be confirmed with a swab if necessary, but treatment should be started even without this. A high vaginal swab in women experiencing treatment failure or recurrent symptoms is useful to confirm diagnosis and sensitivities where resistance (which is uncommon) is suspected.

Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis is defined as four or more episodes per year. Traditionally, it has been thought that oral and topical treatments are equally effective in women with uncomplicated, acute VVC; however, authors of a 2020 Cochrane review7 conclude that oral antifungal treatment probably improves short- and long-term mycological cure over intra-vaginal treatment. In general, patients prefer oral treatment,8 which is still unfortunately prescription-only in Ireland.

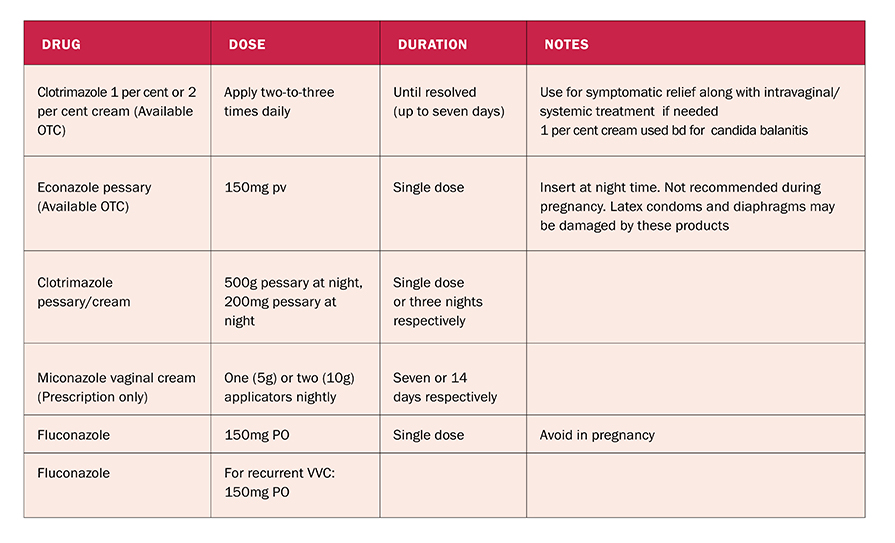

The currently recommended treatment for recurrent VVC rarely cures this condition, but aims to suppress symptoms. Initially, high doses of oral or topical antifungal agents are used for up to two weeks to improve symptoms.5 In severe cases, the suppression of symptoms may take up to six months. Long-term regular antifungal treatment may be required for maintenance of clinical remission (see Table 2 for treatment options).

TABLE 2: Pharmacological treatments for thrush6

Patients with thrush should be advised to avoid tight-fitting clothing and the use of soaps and shower gels. The HSE advises that the use of emollient creams and hydrocortisone 1 per cent cream may help to ease symptoms of vulvitis and balanitis.6 The British Association of Dermatologists has a Care of Vulval Skin leaflet (available online: www.skinhealthinfo.org.uk/condition/care-of-vulval-skin/) that may be useful for patients.9

There is weak evidence that use of probiotics as an adjuvant therapy for the treatment of thrush can improve short-term outcomes, but not long-term.10 More randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with standardised methodologies, longer follow-up, and larger sample sizes are required to determine the impact of probiotics on thrush.

Bacterial vaginosis

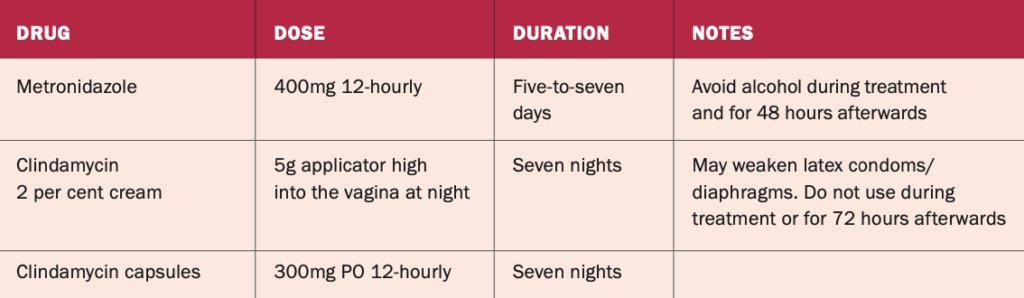

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a common cause of vaginal discharge (white, non-irritating, malodorous), often more noticeable after sexual intercourse.11 Diagnosis, like with candida, can be made on the basis of the description and appearance of discharge, with treatment being started without taking a swab. The normal pH of the vagina is usually increased from <4.5 to up to six, which indicates a replacement of the normal lactobacilli with anaerobic organisms. Women experiencing repeated episodes may find the use of lactic acid vaginal gels useful to facilitate the restoration of healthy vaginal flora (see Table 3 for treatment options).

TABLE 3: Pharmacological treatments for bacterial vaginosis11

Women’s health in Ireland

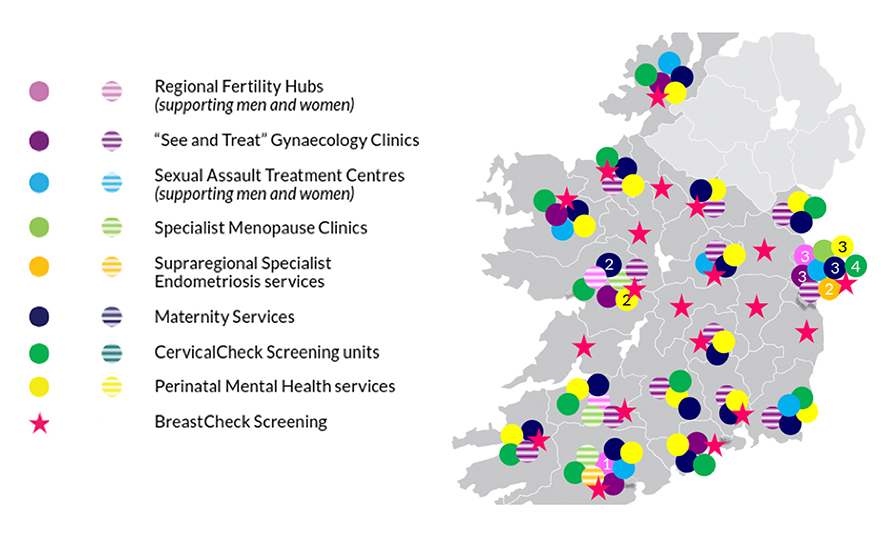

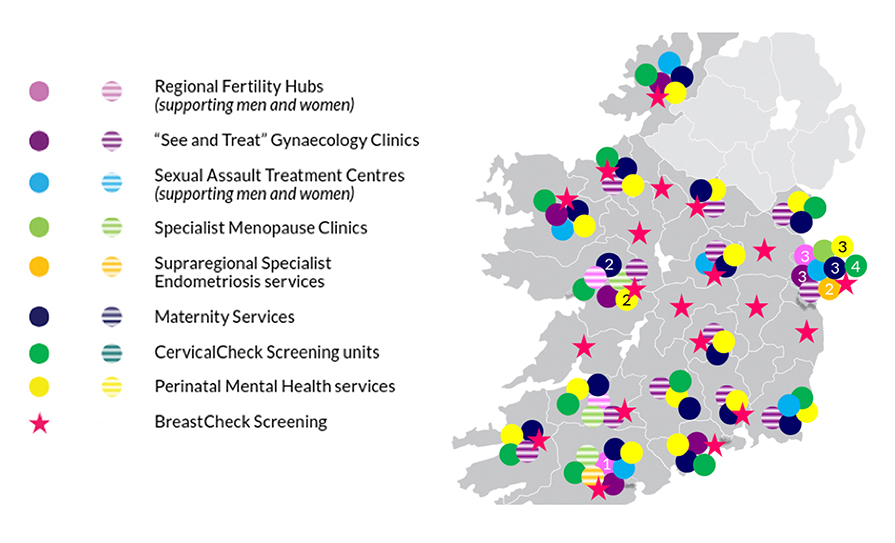

Our Government has introduced a Women’s Health Action Plan (2022-2023) with the aim of improving health services for women in Ireland.12 The plan includes the provision of more funding for the National Maternity Strategy, free contraception for women aged 17-to-26 years, increased access to women’s health clinics (specialist services in gynaecology, menopause, endometriosis clinics), and further funding for future innovative approaches. Figure 1 shows the location of planned and existing services described in the action plan.

FIGURE 1: Women’s health in Ireland 2022: Illustrative map of existing and planned services

The Women’s Health Action Plan (2022-2023) notes that while each woman is different, women who are economically disadvantaged, migrant women, women who are members of minority groups, survivors of domestic abuse, women who have grown up in or on the edge of State care, or women with a disability can experience particular health challenges. The action plan says that the mission of the Department of Health is to improve the health and wellbeing of all people in Ireland.

On average, out of every 1,000 women screened in Ireland for breast cancer, seven will be diagnosed with breast cancer

Women’s health screening in Ireland

Currently, there are three national cancer screening programmes in Ireland: BreastCheck, CervicalCheck, and BowelScreen. These aim to reduce morbidity and mortality in the population through prevention or early detection of cancer, improving the likelihood of better outcomes. Substantial evidence shows that screening programmes result in a greater proportion of early-stage cases (stage I and II) among diagnosed cancers. The National Cancer Registry in Ireland estimates that,13 on average, there were 6,524 cases of breast, cervical and colorectal cancers diagnosed (6,490 excluding male breast cancers), and 1,834 deaths due to these cancer types (1,828 excluding male breast cancers) each year in Ireland over the period 2017-2019.

Since the year 2000, the National Breast Screening Programme in Ireland (BreastCheck) has offered all women between the ages of 50 and 69 a mammogram every two years. Women in this age range benefit most from a breast screening programme. On average, out of every 1,000 women screened in Ireland for breast cancer, seven will be diagnosed with breast cancer.14 There are many online resources to help women understand how to help prevent and check for breast cancer. The Marie Keating Foundation website has advice and a video to show how to self-check for any changes.15

The National Cervical Screening Programme, which tests if a woman is at risk of developing cervical cancer, has been available to women aged 25-to-65 since 2008. Cervical screening checks for the presence of the human papillomavirus (HPV), which causes up to nine-in-10 cervical cancers. It also checks the cells in the cervix: Abnormal cell changes can eventually result in the development of cancer. The CervicalCheck website provides a facility for women to check when their next test is due. The HPV vaccine is now offered for free to young people in their first year at secondary school, and is an effective way to prevent many cases of cervical cancer.16

References

Crimmins EM, Shim H, Zhang YS, Kim JK (2019). Differences between men and women in mortality and the health dimensions of the morbidity process. Clinical Chemistry. 65(1), 135-145

National Institutes of Health (2023). Women’s health. Available at: www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/womenshealth

Mellor Y (2018). Heavy menstrual bleeding: Diagnosis and management options. The Pharmaceutical Journal. Available at: https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/heavy-menstrual-bleeding-diagnosis-and-management-options

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018). Heavy menstrual bleeding: Assessment and management [NICE Guideline No 88]. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88/resources/heavy-menstrual-bleeding-assessment-and-management-pdf-1837701412549

Cooke G, Watson C, Deckx L, Pirotta, M, Smith J, van Driel ML (2022). Treatment for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (thrush). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1). Available at: www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009151.pub2/full?highlightAbstract=candidiasis %7Ccandidiasi

Health Service Executive (2021). Antibiotic prescribing – Candida, genital thrush. Available at: www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/2/gp/antibiotic-prescribing/conditions-and-treatments/genital/vaginal-candidiasis/

Denison HJ, Worswick J, Bond CM, Grimshaw JM, Mayhew A, Ramadoss SG, Watson MC (2020). Oral versus intra-vaginal imidazole and triazole anti-fungal treatment of uncomplicated vulvovaginal candidiasis (thrush). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8)

Nurbhai M, Grimshaw J, Watson M, Bond CM, Mollison JA, Ludbrook A (2007). Oral versus intra-vaginal imidazole and triazole anti-fungal treatment of uncomplicated vulvovaginal candidiasis (thrush). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4)

The British Association of Dermatologists (2023). Care of vulval skin. Available at: www.skinhealthinfo.org.uk/condition/care-of-vulval-skin/

10. Xie HY, Feng D, Wei, DM, Mei L, Chen H, Wang X, Fang F (2017). Probiotics for vulvovaginal candidiasis in non-pregnant women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11). Available at: www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010496.pub2/pdf/full

11. Health Service Executive (2021). Antibiotic prescribing: Bacterial vaginosis. Available at: www.hse.ie/eng

/services/list/2/gp/antibiotic-prescribing/conditions-and-treatments/genital/bacterial-vaginosis/

12. Department of Health (2022). Women’s Health Action Plan 2022-2023. Available at: www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/218275/61c989ed-d115-48a4-94ea-a915bfbf638f.pdf#page=null

13. The National Cancer Registry in Ireland (2021). Cancer trends. Available at: www.ncri.ie/sites/ncri/files/pubs/Trendsreport_breast_cervical_colorectal_22092022.pdf

14. Health Service Executive (nd). BreastCheck: Important information about your breast screening. Available at: https://assets.hse.ie/media/documents/Important_information_about_your_breast_screening.pdf

15. Marie Keating Foundation (2023). How to check your breasts. Available at: https://mariekeating.ie/cancer-information/breast-cancer/be-breast-aware/

16. Health Service Executive (2022). What cervical screening is. Available at: www2.hse.ie/conditions/cervical-screening/why-go/what-cervical-screening-is/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.