Male lower urinary tract symptoms are a frequent presentation to both GP practices and urology clinics, and are commonly due to benign prostatic hyperplasia

Case Report

Referral: A 56-year-old man was referred to the urology clinic by his GP with slowly progressive lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), despite medication with a combined alpha-blocker and 5-alpha reductase inhibitor (5ARI).

History: The gentleman reported LUTS in the form of a slow stream, hesitancy initiating, intermittency of the stream, straining to void and a sensation of incomplete emptying, along with urinary frequency and nocturia three times per night. He had been started on Combodart three years prior, initially with a good improvement, but had noticed a progressive decline in symptoms over the preceding year. He reported no visible haematuria, urinary tract infections (UTIs), or nocturnal enuresis.

His past medical history was significant for hypertension, controlled on single-agent pharmacotherapy, and his only other medication was Combodart. He was a non-smoker and had removed caffeine from his diet due to LUTS. He worked at a desk job. He reported his quality-of-life to be significantly impaired by his LUTS.

His International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) was 20, classifying his LUTS as severe. He completed a three-day bladder diary, which confirmed frequent voids of relatively low volumes and nocturia x three, without nocturnal polyuria.

Examination: Examination revealed an elevated BMI, normal external genitalia, and an enlarged smooth prostate estimated >60g on digital rectal examination (DRE).

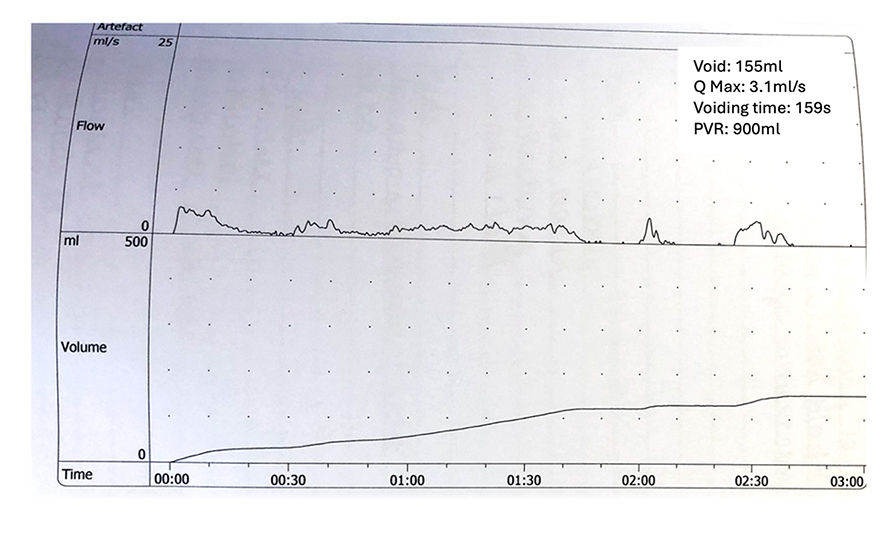

Investigations: Urinalysis was normal. Serum creatinine was 90umol/L and PSA was 1.4ng/mL on a 5-ARI. Other laboratory bloods were within normal ranges. Uroflowmetry (See Figure 1) revealed a voided volume of 155ml, a very low maximum flow rate (QMax) of 3.1ml/s, a prolonged voiding time of 159s and a flat obstructed curve with intermittency. Post-void residual volume (PVR) was 900ml. He underwent flexible urethro-cystoscopy and this confirmed no urethral stricture, a prostate with trilobar occlusive enlargement with intravesical extension, and a mildly trabeculated bladder without urothelial abnormality.

Management: The gentleman was educated by a urological clinical nurse specialist in intermittent self-catheterisation (ISC) to address his high residual volumes in the first instance. He was counselled regarding all potential management options, including continuing long-term ISC. He was keen for definitive treatment and elected to undergo bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). The procedure involved a large resection as anticipated, but was uncomplicated, with a resection time of 70 minutes. He underwent a successful trial without catheter on the ward, with a PVR of 80ml.

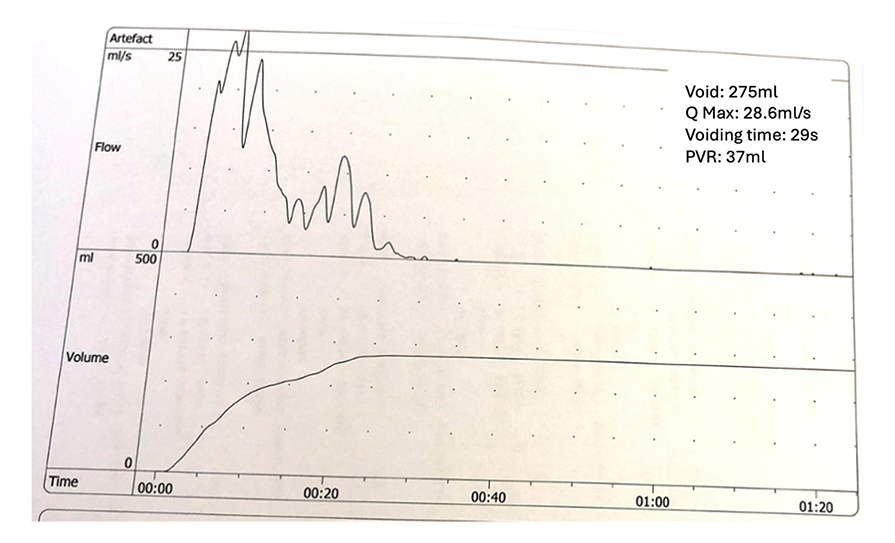

Follow up: He was seen in the outpatient clinic six weeks post-procedure. He reported a marked improvement in his urinary symptoms since the procedure, with an IPSS score now of two. Histology confirmed resection of 33g of benign prostate chippings (BPH). He performed a repeat uroflow (See Figure 2), voiding 275ml of urine over 29 seconds with a QMax of 28.6ml/s and a PVR of 37ml. He was discharged back to the care of his GP.

Benign prostatic enlargement

Background, definition and epidemiology

The gentleman in our case report suffered from bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) secondary to prostatic enlargement; histologically confirmed as benign prostatic

hyperplasia (BPH) – a non-malignant process resulting in enlargement of the prostate gland.

Epidemiology

BPH is highly prevalent, and is the most common urological disease diagnosed in the ageing male. Figures estimate a pathological diagnosis of BPH in approximately 50 per cent of men aged >50 years and >80 per cent of men aged >70.

Pathophysiology and risk factors

The prostate gland is composed of a combination of fibromuscular stroma and glandular elements and is roughly the size of a walnut in the young adult male, weighing 18-to-20g.

BPH results from an increase in the number of epithelial and stromal cells in the paraurethral zone of the prostate.Prostate volume in the older male was observed to increase at an average rate of 0.6ml/year, albeit with much variability, in one longitudinal study. As the prostate enlarges, obstruction of the bladder outlet may ensue via both ‘static’ and ‘dynamic’ mechanisms, (ie, prostate volumetric increase and prostatic smooth muscle contraction). Genetics and other incompletely-understood factors contribute to the pathogenesis of BPH, with other potential risk factors including obesity, hypertension, diabetes, diets deficient in fruit, vegetables and fibre, and sex hormone levels implicated in its development also.

Clinical consequences

BPH may be asymptomatic. It may also cause BOO, resulting in LUTS and/or acute or chronic urinary retention. The patient in our case study presented with chronic urinary retention. Such high residual volumes of urine within the bladder predispose a patient to UTIs, which may present as cystitis, epididymo-orchitis or pyelonephritis.Whilst our patient had low-pressure chronic retention with normal renal function, chronic urinary retention may also present in a ‘high pressure’ state, where elevated intravesical pressures are transmitted to the upper urinary tracts, resulting in hydronephrosis and renal impairment that may be associated with life-threatening electrolyte disturbances and irreversible renal impairment.

Presentation and clinical history-taking

BOO secondary to benign prostatic enlargement may present with a variety of LUTS, as demonstrated in the case report in this article. These may include classically obstructive LUTS, such as slow stream and intermittency, and storage type LUTS, such as frequency and nocturia, likely driven by incomplete emptying. Haematuria may occur, but requires full and urgent investigation for other causes, such as underlying urothelial malignancy, in the first instance. The presence of nocturnal enuresis (bed-wetting) is a sign of high-pressure chronic retention, and should prompt urgent assessment of post-void bladder volume along with renal function, and serum electrolytes. Clinical history taking should also elicit the presence of any neurological symptoms or history of spinal trauma suggestive of a neurological cause of LUTS, the presence of medical conditions that may cause or exacerbate LUTS (eg, chronic constipation, diabetes/other endocrine disorders, obstructive sleep apnoea, COPD, cardiovascular disease or diuretic requirements) or influence treatment options. Additionally, it is imperative to explore lifestyle factors, such as voiding behaviours, fluid, and caffeine intake.

The extent of LUTS and their impact on a patient’s quality-of-life may be quantified using the validated International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), and a frequency-volume chart or bladder diary can assess lifestyle factors, fluid intake, voiding behaviour, functional bladder capacity, and the diagnosis of nocturnal polyuria if present.

Physical examination

Physical examination will include suprapubic palpation (assessing for a distended bladder), penoscrotal examination to rule out penile lesions, meatal stenosis or a tight phimosis, a digital rectal examination (DRE), and a neurological examination of the lower limbs. DRE will estimate prostatic size and assess the surface contour and consistency of the palpable peripheral zone of the prostate, with firm/hard regions or nodules raising possibility of malignancy.

Further diagnostic assessment

Urinalysis should be performed in all patients presenting with LUTS and is important to detect urinary tract infection, non-visible haematuria or evidence of renal dysfunction. Bloods should be taken for serum urea, creatinine, and electrolytes.

A prostate specific antigen (PSA) test may be offered to appropriately counselled patients. Whilst PSA has utility as a screening tool for prostate cancer and an additional role in predicting prostatic volume and BPH progression, patients should be informed regarding implications, risks, benefits, and possible consequences of PSA testing, prior to deciding to proceed.

Within urology services, uroflowmetry will be performed, which plots the velocity of urinary stream over time on a graph and can suggest potential obstruction. It has been shown that 90 per cent of men with a QMax <10ml/s are suffering from BOO. Review of Figure 1 pertaining to our case report shows a QMax of only 3.1ml/s.

PVR assessments (bladder scans) are imperative to evaluate for incomplete bladder emptying, with values >300ml considered indicative of chronic retention.

Cystourethroscopy may be required for a variety of reasons, including the presence of haematuria or suspicion of a urethral stricture and cystometrogram (CMG) may be indicated for non-straightforward cases of male LUTS (such as young age, equivocal findings on uroflowmetry, the presence of a neurological condition, a history of prior radical pelvic surgery or prior surgical intervention for BPH). Some advocate CMG in the presence of high PVRs, as seen in this case, to assess for detrusor hypocontractility, which may result in failure to resume normal voiding, even after BOO is surgically addressed. However, contemporary metanalysis has shown that significant symptomatic and urodynamic improvements across all parameters, including bladder contractility, may occur following surgical correction of BOO in patients with pre-operative detrusor underactivity. We do not routinely perform CMG on these patients, but counsel patients extensively to understand that adequate bladder emptying is not always achieved by surgery.

Renal ultrasonography or other upper tract imaging is not routine in the evaluation of uncomplicated LUTS, but is warranted in the presence of abnormal renal function or for other specific indications.

Management options

A range of management strategies may be utilised for patients with BPH.

I. Conservative

Patients who are minimally bothered with mild or moderate symptoms may simply undergo observation. They should receive education regarding lifestyle measures that may contribute to LUTS or increase the risk of acute urinary retention (evening/nocturnal fluid intake, caffeine, C2H5OH, constipation, and nasal decongestants). Patients should be advised of the risk of BPH progression. Based on a longitudinal study of 400 men, clinical progression is expected in approximately one-in-three men and acute urinary retention in approximately one-in-20 over a four-year period.

II. Medical

u α1-adrenergic antagonists block α1 receptors at prostatic smooth muscle and the bladder neck, resulting in smooth muscle relaxation with improvement in voiding parameters. Tamsulosin is the best known of these; silodosin has been shown to exert more selectivity for α1A adrenoreceptors versus α1B adrenoceptors and may reduce the risk of postural hypotension in susceptible patients.Adverse effects include retrograde ejaculation, nasal congestion, dry mouth, and fatigue.

u Whilst less commonly used for LUTS alone, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil or tadalafil, cause smooth muscle relaxation and regular use has been associated with an improvement in LUTS in men with or without erectile dysfunction.

u The steroid 5α-reductase inhibitors (5ARIs), finasteride, and dutasteride, aim to reduce prostatic volume and may be administered alone or alongside an α1-adrenergic antagonist. 5ARIs work by blocking the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Improvements in symptoms are not expected for four-to-six weeks and three-to-six months of consistent treatment are required for full efficacy. They are generally well-tolerated, however, possible adverse effects include loss of libido, sexual dysfunction, and mood alteration. Whilst these generally resolve on drug cessation, there is emerging evidence that some adverse effects they may persist in a small minority and patients should be counselled in this regard prior to commencement.

u In patients with prominent storage symptoms (eg, frequency, urgency, nocturia), an element of bladder overactivity (OAB) may be at play. It is thought that BOO over time can trigger detrusor instability and result in this. As similar symptoms can occur in BOO patients with high residual volumes/chronic retention, it is desirable to obtain a post-void bladder volume scan. Men with marked storage symptoms and PVRs <150ml may benefit from the addition of muscarinic receptor antagonists (eg, solifenacin, tolterodine, fesoterodine) or beta-3 adrenergic agonists (eg, mirabegron) to BOO medications. There may be potential of increasing the chance of urinary retention with this approach, but the risk appears low.

III. Surgical/interventional

A plethora of surgical treatments exist for the management of symptomatic BPE.

u The most common procedures aim to remove or destroy prostate tissue, creating an open bladder outlet channel for voiding. A variety of surgical techniques and energy sources may be applied to this end. The most ubiquitous procedure is electrocautery transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), which the patient in our case report underwent using a bipolar instrument. Other techniques include LASER or water vapourisation.

u Urethral lift surgery is a minimally-invasive procedure, often performed as a day-case. It involves placement of small implants to compress or ‘lift’ the prostate away from the urethra and improve urinary flow. As a more modern innovation, robust data on long-term outcomes remain incomplete. However, a lower rate of ejaculatory dysfunction as compared to many other surgical treatments make this an appealing option to some men.

u Enucleation or adenectomy, the removal of all prostatic tissue from the prostatic capsule, is another surgical option. This is generally performed for patients with very large prostates. This may be performed by open or minimally-invasive (eg, robot-assisted) prostatectomy or via transurethral laser enucleation techniques, such as HoLEP.

IV. Interventional radiological

Prostatic artery embolisation (PAE) aims to selectively embolise the prostate’s arterial blood supply, with resultant tissue necrosis and shrinkage of the gland. Fewer outcome data regarding satisfaction and efficacy are available compared to alternative treatments. PAE remains an uncommonly performed procedure overall in Ireland. It may have a particular role in patients with large, highly-vascularised prostates requiring a minimally-invasive approach that can be performed without general anaesthesia.

V. Catheterisation

Whilst not a desirable option for many patients, urinary catheters continue to serve a role for some patients with BOO secondary to BPE. For patients suffering bothersome LUTS, high PVRs or recurrent urinary retention, who have not experienced benefit from, wish to avoid, or are medically high-risk for alternative treatment strategies, catheterisation may be considered. Preferably this is via intermittent self-catheterisation for patients with the cognitive and physical abilities to perform this following education. Alternatives are long-term indwelling urethral or suprapubic catheters.

Conclusions

Male LUTS are a frequent presentation to both GP practices and urology clinics, and are commonly due to BPE. This may run an indolent course or result in troublesome symptoms, acute urinary retention, urological infections, and high pressure chronic urinary retention, which can result in permanent renal damage if undiagnosed.

Initial assessment includes a thorough history, augmented by an IPSS score and bladder diary, a physical examination incorporating a DRE, urinalysis, laboratory bloods with urea, creatinine and electrolytes, a measurement of PVR and uroflowmetry and, in addition, PSA in counselled patients wishing to proceed.

Management options include observation, pharmacological treatment, surgery, and for a minority of patients, long-term catheterisation or intermittent self-catheterisation. As demonstrated by our case report, TURP can result in dramatic improvements in both patient symptoms and objective voiding parameters on uroflowmetry.

References on request

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.