An overview of the asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis relationship, and treatment approaches

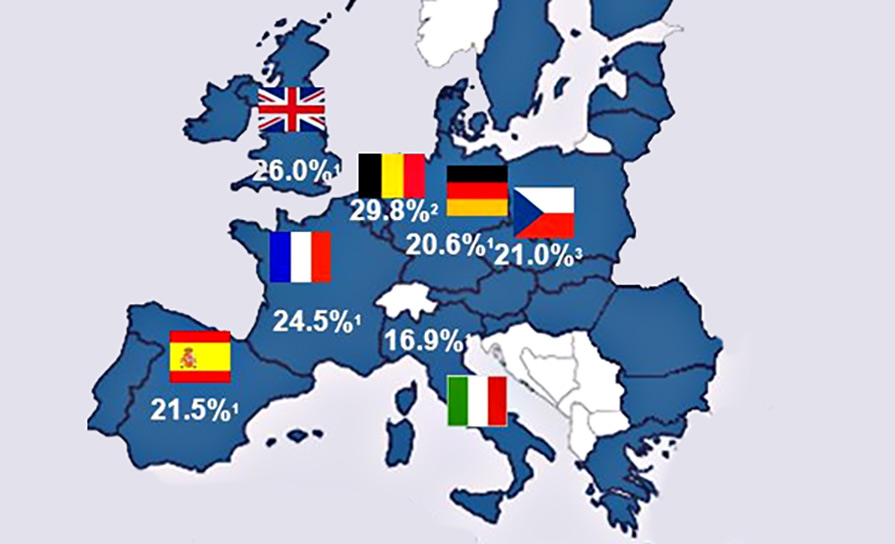

For many years there has been a clearly described association between chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) and asthma, with a prevalence of around 25 per cent of asthma in those with CRS, compared to a prevalence of up to 10 per cent in the general population.

In patients with asthma, up to 90 per cent of those with allergic asthma describe rhinitis and up to 80 per cent of those with non-allergic asthma. In the adult population, CRS has been defined as the presence of two or more symptoms, one of which should be either nasal blockage, obstruction or congestion; or nasal discharge (ie, anterior or posterior nasal drip) with or without facial pain/pressure; or reduction or loss of smell; for at least 12 weeks.

Previously, CRS has been divided into two groups based on clinical history and nasoendoscopic exam, either with or without nasal polyps. In recent years there has been an increase in interest and popularity of the concept of a united airways disease, also sometimes termed global airways disease.

It is suggested that if the role of the upper airway to act as a humidifier, filter and heat regulator for air entry onwards into the lower airways is disrupted, it leads to more generalised inflammation progressing to the lower airways.

Allergic rhinitis has long been considered a risk factor for the development of asthma, but there is some speculation that this is truly the early presentation of a reactive airways disease, which may then progress to asthma. There is a commonality in the factors which can trigger upper and lower airways disease.

These include allergens, aspirin, infections both viral and bacterial, or irritants such as pollutants. Also at a cellular level, the infiltrates that characterise inflammation in both asthma and CRS include eosinophils, mast cells, macrophages and T-cells.

Cytokines promoting inflammation are also similar, such as histamine, interleukin 4, 5 and 13, and leukotrienes. This correlates with CRS being associated with the asthma clinical subgroup of TH2 dominant asthma, which includes allergic and eosinophilic asthma.

The relationship between allergy and allergic rhinitis and the development of CRS remains unclear and incompletely understood, as CRS has not been considered as related to atopy, unlike allergic rhinitis. Recent studies suggest in the setting of sinusitis, grouping patients on their inflammatory patterns into either type 1 or type 2 inflammation is more useful than general atopic status.

Also, in patients with upper airway sinus disease and lower respiratory symptoms it is important to consider other causes/associations outside of asthma, including vasculitis such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA).

In asthmatic patients, symptoms of CRS contribute significantly to quality-of-life, however, this is largely in relation to poorer asthma control due to upper airway disease.

The outcomes of poorer asthma control apart from quality-of-life including work days missed, exposure to more frequent courses of antibiotics and steroids as well as increased State spending on hospitalisations and maintenance therapy have a clear population impact.

Data from the Asthma Society of Ireland published last year revealed overall State spending of €473 million per annum on asthma.

Treatment

Treatment aims in CRS are to reduce inflammation and associated oedema, allow for adequate sinus drainage, eliminate any colonising or infecting organisms and to reduce the number of acute exacerbations. Asthma is usually associated with diffuse bilateral sinus disease, the mainstay of treatment of which is intranasal corticosteroids and saline.

Adequate delivery and technique, as well as compliance with this quite cumbersome therapy is of vital importance for treatments to have beneficial effect. Local delivery can be enhanced by saline irrigation prior to use of other topical agents, angling of the head slightly downwards, and aiming the tip of the spray away from the nasal septum.

Antimicrobial therapy in CRS has limited evidence, outside of acute exacerbations. A single course of antibiotics may often be used, especially if increasing purulent nasal discharge. In some post-operative patients there may be sinus cultures available, but generally an empiric regimen is chosen.

This would need to cover anaerobic organisms, staph aureus and streptococci. Broad-spectrum agents such as co-amoxiclav and doxycycline are routinely prescribed. Doxycycline offers a synergistic anti-inflammatory effect in theory and has been shown to reduce nasal polyp size.

Longer-term suppressive antibiotics including macrolides are sometimes used in secondary care, however, there is currently a low quality of evidence to support same and side effects of such should certainly be considered.

Oral steroids are often used in the short-term for those with refractory symptoms, and can be particularly beneficial in those with nasal polyps. Leukotriene receptor antagonists such as montelukast are used as an adjunct therapy to nasal corticosteroids and seem to show additional benefit in CRS patients with asthma or aspirin-exacerbated airways disease.

If symptoms are not responsive to usual treatment, CT of the sinuses as well as otorhinolaryngology review is recommended by the European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020, which can identify any more localised disease, as well as suitability for surgical intervention.

Endoscopic sinus surgery in asthma has been reported to improve multiple clinical asthma parameters with improved overall asthma control, reduced frequency of asthma attacks and number of hospitalisations, as well as decreased use of oral and inhaled corticosteroids.

However, of note, endoscopic sinus surgery’s role is to optimise local treatment and as CRS is a chronic condition, ongoing medical management is still required. Naturally, this is also the case with ongoing treatment of asthma as a chronic condition.

A developing area of interest in CRS, as it is in asthma treatment, is biologic therapy. Dupilumab was the first monoclonal antibody approved as an add-on therapy for CRS with nasal polyps by the European Commission in 2019. It is an interleukin 4 receptor antagonist, and modulates signalling of interleukin 4 and 13.

For asthma, omalizumab is approved for those with severe persistent asthma, with clear IgE mediation. Phase 3 trials published last year showed significantly reduced nasal congestion and polyps in those with CRS, while a previous study has shown a similar benefit in alleviation of sinus symptoms with omalizumab in a cohort with co-existing severe allergic asthma and CRS with polyps. There have been no efficacy studies examining CRS without polyps.

Mepolizumab, an anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody, is approved for those with severe refractory eosinophilic asthma. A phase 3 trial preliminary data published earlier this year for mepolizumab also suggested positive results in relation to size of nasal polyps and relief of obstruction, again in CRS without polyps.

However, given the costly nature of these drugs, significant study is still needed into cost benefit analysis as well as very careful patient selection and optimisation of other therapies.

Role of joint care

If we look at the overlapping problems of asthma and CRS as a united airways disease, it certainly does seem strange to have it managed very separately by respiratory and otorhinolaryngology, often across different centres.

Close collaboration between respiratory and otorhinolaryngology specialists leads to improved access to care and therefore intervention for asthmatic patients with difficult to control disease. In our centre, this has led to the establishment of a joint respiratory and rhinology clinic. Certainly patients anecdotally self-report improved satisfaction with access to both services with one appointment, rather than remaining on waiting lists with ongoing symptoms or exacerbations.

The management and outcomes of these patients is being evaluated in ongoing research.

References

- Sibbald B, Rink E. Epidemiology of seasonal and perennial rhinitis: clinical presentation and medical history. Thorax. 1991;46(12):895-901. doi:10.1136/thx.46.12.895

- Ciprandi G, Caimmi D, Miraglia Del Giudice M, La Rosa M, Salpietro C, Marseglia GL. Recent developments in United airways disease. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2012;4(4):171-177. doi:10.4168/aair.2012.4.4.171

- Phillips KM, Talat R, Caradonna DS, Gray ST, Sedaghat AR. Quality-of-life impairment due to chronic rhinosinusitis in asthmatics is mediated by asthma control. Rhinology. 2019;57(6):430-435. doi:10.4193/Rhin19.207

- Schlosser RJ, Smith TL, Mace J, Soler ZM. Asthma quality of life and control after sinus surgery in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy. 2017;72(3):483-491. doi:10.1111/all.13048

- Asthma Society of Ireland. www.asthma.ie/get-help/resources/facts-figures-asthma

- Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Hopkins C, et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020. Rhinology. 2020;58(Suppl S29):1-464. Published 2020 Feb 20. doi:10.4193/Rhin20.600

- Bidder T, Sahota J, Rennie C, Lund VJ, Robinson DS, Kariyawasam HH. Omalizumab treats chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps and asthma together – a real life study. Rhinology. 2018;56(1):42-45. doi:10.4193/Rhin17.139

- Fokkens WJ, Lund V, Bachert C, et al. EUFOREA consensus on biologics for CRSwNP with or without asthma. Allergy. 2019;74(12):2312-2319. doi:10.1111/all.13875

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.