“Dúirt bean liom go ndúirt bean léi” –“a woman told me that a woman told her” – seanfhocal (Irish proverb).

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has declared the ‘infodemic’ – an overabundance of information and rapid spread of misleading or fabricated news, images and videos – as one of the greatest threats to global health.

Atopic dermatitis (AD), or eczema, has a complex multifactorial aetiology, involving skin-barrier dysfunction, dysbiosis and T helper 2 cell-skewed immune pathways. Sophisticated scientific concepts are at higher risk of formulation and dissemination of misinformation. One recent study showed that over two-thirds of YouTube videos related to AD were of poor or very poor scientific quality. Moreover, treatments for AD such as topical corticosteroids (TCS) have also been subject to much misinformation in recent years. TCS phobia, also known as ‘corticophobia’, involves vague negative feelings and/or erroneous beliefs about TCS held by patients and caregivers that can be promoted by misinformation. TCS have been used as a safe and effective treatment for many inflammatory dermatological diseases since their introduction over 70 years ago. When used properly, they can prevent the need for

systemic immunosuppressive agents with more severe side-effect profiles. Poor compliance is a common obstacle to successful disease control, and non-adherence to prescribed TCS can be due to TCS phobia.

Research study

We recently performed research examining the content of misinformation available online for both AD and TCS. We performed literature reviews on PubMed using combinations of terms including ‘atopic derma- titis’, ‘atopic eczema’, ‘eczema’, ‘topical corticosteroids’, ‘misinformation’, ‘disinformation’, ‘conspiracy theories’, and reviewed the searches for suitable content. We also performed Google searches and targeted searches on social media (Facebook, Twitter, Insta- gram, and TikTok) to identify misinformation.

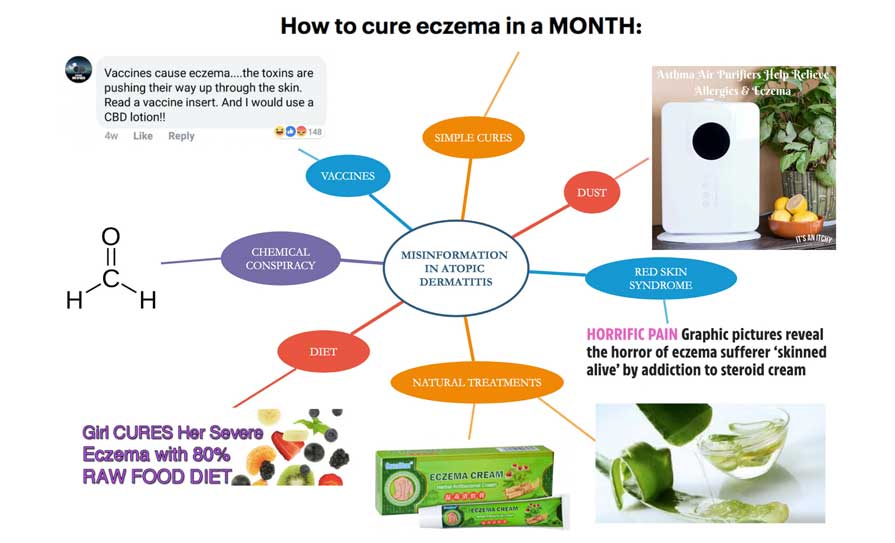

For AD, thematic analysis of search results identified key areas of misinformation, including ‘simple cures’ for AD, diet, chemicals, dust, vaccines, red skin syndrome, and alternative therapeutic regimens (Figure 1). For TCS, key areas of misinformation identified included ‘topical steroid addiction’ or ‘withdrawal’, exaggeration of potential adverse effects, focusing on alternative ‘underlying’ causes, and recommending alternative ‘natural’ treatments. Relevant hashtags for TCS misinformation included #steroidphobia, #corticophobia, #topicalsteroidwithdrawal, #topicalsteroidaddiction, #tswwarrior, #itsan, #redskinsyndrome, #redskinsyndromejourney, #redskinsyndromewarrior. On TikTok, there were 323 million views of #topicalsteroidwithdrawal, 510.3 million views of #tsw, and 41.4 million views of #topicalsteroidaddiction.

Simple cures for AD were frequently mentioned, suggesting that AD was caused by a minor issue and could be reversed by avoidance of relevant trigger(s). Various causes were suggested, including foods, chemicals, dust, vaccinations, emollients, and topical steroids. This did not consider that the aetiology of AD involves multiple factors and that avoidance of specific individual environmental exposures is unlikely to be helpful.

Diet

Exclusion of multiple different foods was incorrectly recommended to ‘cure’ AD, including dairy, eggs, nuts, fish, and gluten-containing foods. Vegan diets were reported to ‘cure eczema in days’. In AD, disruption of the skin barrier increases the risk of food allergy due to cutaneous exposure to food protein, leading to allergic sensitisation, but food allergies do not directly cause AD. In fact, inappropriate dietary restriction in AD can paradoxically increase the risk of true food allergy. Fad diets were also recommended for ‘leaky gut syndrome’, based on a false hypothesis that normal foods can increase intestinal permeability and cause AD.

Blame game

Several chemicals have been mistakenly cited as causes of AD. The ‘formaldehyde conspiracy’ claims that the presence of formaldehyde in food and cleaning products causes AD. The ‘detergent conspiracy’ suggests that the recent increase in AD prevalence is secondary to an increase in the use of washing detergents.

Dust has also been incorrectly implicated as a cause of AD. Air purifiers have been touted, usually by companies selling these devices, to both prevent and cure AD. While house dust mite allergy might exacerbate cutaneous as well as airway allergic disease, there is no evidence that dust particles cause AD. AD has also infrequently been attributed to 5G wireless technology.

Some websites claim that vaccines elicit immune responses or contain ingredients that provoke AD in genetically-susceptible individuals. One homeopathy company frequently shared disinformation about ‘poisonous’ vaccines causing AD. The example of smallpox vaccination causing eczema vaccinatum has been extrapolated to suggest that all vaccines cause AD. Vaccine-related misinformation undermines the safety of this vital public health measure, especially important in the Covid-19 pandemic.

‘Natural’ remedies

So-called ‘natural’ remedies are also frequently recommended to treat AD, such as apple cider vinegar, calendula, and witch hazel, which are all unproven therapies. One 14-month-old child in Canada reportedly died of septic shock, exacerbated by nutritional deficiencies, following prolonged nutritional restriction and use of natural remedies as treatments for AD. ‘Natural’ Chinese herbal ointments are frequently used by parents who have concerns about prolonged use of topical steroids. However, it is known that a significant proportion of these products contain super-potent topical steroids, ironically placing patients at increased risk of adverse effects. Frequently mentioned in our outpatient department, is a prescribed regimen that is a combination of corticosteroid, emollient and fusidic acid, combined in one formulation. This approach may cause antimicrobial resistance and dilutes the effectiveness of topical steroids.

Steroid demonisation

‘Red skin syndrome’, also referred to as ‘topical steroid addiction’, is a popular topic on eczema internet forums and tabloid newspapers. One proponent of this theory claims that AD is caused by topical steroid addiction and offers a teledermatology service to cure it, with testimonials to support this mode of treatment. Content creators have highlighted their ‘journey’ with #TSW, explaining that they initially had mild eczema, then required increasingly potent TCS. They then withdraw TCS abruptly, and unsurprisingly have a flare of their underlying AD, which is explained as a benign withdrawal reaction which will resolve spontaneously if TCS are avoided. Implausible underlying causes are usually reported for their AD, typically a ‘leaky gut’, with no further explanation as to what this means. Food allergies or intolerances are also frequently mentioned as a cause of their AD, which is well-recognised as being untrue.

The National Eczema Society and the British Association of Dermatologists have released a joint paper on topical steroid withdrawal, clarifying that symptomatology can be explained by uncontrolled severe AD, consequences of abruptly stopping TCS, rare TCS contact allergic dermatitis, or uncommon side-effects of TCS, eg, atrophy, rosacea, acne, or perioral dermatitis. Extremely, some topical steroid withdrawal proponents have proposed total water deprivation (both topical and oral) as a method to manage topical steroid withdrawal (by ‘recalibrating the body’s ability to retain moisture’), with potentially deadly effects. Unstopped, this vicious cycle of misinformation could result in uncontrolled disease, and dangerous health effects for patients.

Several websites misleadingly claim that other topical treatments cause AD. One website claims that emollients induce AD and promises that their digital programme (£49) cures AD. Conversely, some websites suggest that TCS are not needed if enough emollient is applied instead, and highlight the need to avoid TCS application on skin that is ‘broken or weepy’. Other misinformed posts included suggestions that TCS have antimicrobial effects, and that they are absorbed into the circulatory system. While TCS may reduce the risk of infection by reducing inflammation and enhancing barrier function, they are not directly antimicrobial. Moreover, modern TCS have low percutaneous absorption and are unlikely to have systemic effects.

The main fears expressed by patients regarding TCS included adverse effects on skin thinning and potential effects on growth and development for children. Skin atrophy is an uncommon localised adverse effect of TCS, only occurs with persistent, repeated use of potent TCS at the same anatomical site over a prolonged period, and is reversible with cessation of steroid use. A systematic review examining TCS safety found no evidence of skin thinning when TCS were used intermittently to treat acute AD flares, or as weekend therapy (ie, twice weekly) to prevent AD flares. This review also found no evidence of growth restriction or adrenal suppression. A review of 16 clinical trials assessing the impact of TCS on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPAA) found that TCS are not associated with HPAA suppression, and are extremely safe when used in line with current practice.

Other points of disinformation regarding TCS recommended seeking an ‘underlying’ cause for skin problems, such as food allergies in AD or stress in psoriasis. Advocates of this were frequently affiliated with expensive pseudo-scientific consultations or ‘testing’. ‘Natural’ products (Manuka honey), alternative devices (Hazelwood jewellery) or herbal supplements (calendula) were often promoted at inflated prices, usually with a promise to ‘cure’ skin disease, with no proven scientific evidence.

In summary

AD- and TCS-related misinformation and corticophobia are complex, multifaceted phenomena. AD is associated with significant disruption to quality-of-life. Patients and families are desperate for any potentially beneficial treatment and exposure to misinformation may reduce adherence to evidence-based strategies. Risk factors for corticophobia include misinformation, lack of TCS education, fear of potential side-effects, urban residency, higher education, higher income, higher number of GP attendances prior to dermatology review, and lack of dermatology clinic continuity. The psychosocial and visual impact that dermatological disease can have on patients leaves them desperate to find a quick fix for their cutaneous ailments, and vulnerable to misinformation. This desperation, combined with the overwhelming amount of misinformation about the efficacy and safety of TCS, can lead to patients (and parents) opting for non-adherence to prescribed TCS regimes, or non-conventional treatment options that have not undergone rigorous testing or research. Misinformation regarding AD has serious consequences, and some of the endorsed treatments are potentially lethal. The use of the word ‘cure’, especially if benefit from the suggested intervention seems implausible, should be a red flag that the information is incorrect. Information from companies selling products should also be viewed sceptically. Patients may also psychologically protect their sense of self by blaming external factors (eg, TCS) for their skin disease. Our previous research has shown that mixed messaging from healthcare professionals regarding TCS leads to tension and conflict for families with skin disease.

Prof Robert Proctor, Professor of History of Science at Stanford University, US, has declared this era the “golden age of ignorance”. Healthcare professionals can stop the spread of false information by refuting or rebutting misleading health information and by providing appropriate evidence to accompany their refutation. All doctors, but especially dermatologists and GPs, should be aware of AD-related misinformation circulated by charlatans and be prepared to combat incorrect information to optimise care.

References

1.O’Connor C, Murphy M. Scratching the surface: A review of online misinformation and conspiracy theories in atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46(8):1545-1547. doi: 10.1111/ced.14679

2.Finnegan P, Murphy M, O’Connor C. #corticophobia – a review on online misinformation related to topical steroids. Under review in Clin Exp Dermatol

3.O’Connor C, Dhonncha EN, Murphy M. “His first word was ‘cream’.” The burden of treatment in pediatric atopic dermatitis – A mixed methods study. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(3):e15273. doi: 10.1111/dth.15273

The Irish Skin Foundation (ISF) is a national charity dedicated to improving quality of life for people living with skin conditions. We promote skin health and the prevention of skin disease by offering support, independent information, engaging in advocacy, and raising awareness.

Our free Ask-a-Nurse Helpline provides direct, accessible and specialist guidance about skin conditions on an appointment model https://irishskin.ie/ask-our-dermatology-nurse/

Throughout the year we run events, including public information meetings and community outreach. Details can be found here: https://irishskin.ie/events-calendar/

We offer a trusted suite of independent information on the most common skin conditions for nationwide distribution to GPs and hospitals. These downloadable booklets can be found on our websitehttps://irishskin.ie/information-booklets-resources/

The ISF also contributes and collaborates on research projects, advocates for better public services and access to new therapies, hosts education days and events to broaden access to first-line dermatology education, and many other health promotion activities in communities and hospitals.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.