Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common psychiatric issue faced by Irish children today. Experts claim that up to 5 per cent of school children have ADHD with male children being affected three times more than females of the same age. As there is no laboratory test for ADHD per se, the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) and the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) have developed diagnostic clinical criteria for ADHD to aid accurate diagnosis.

Over recent decades, however, evidence has slowly emerged suggesting that the real statistics of ADHD diagnosis and management in Ireland may have inaccuracies owing to misdiagnosis over more accurately fitting conditions, over diagnosis of otherwise ill-fitting symptoms, and especially in today’s world of Covid-19, under diagnos, due to clinical limitations imposed by the pandemic.

This paper aims to briefly review the evidence that points to the potential instances where misdiagnosis can happen. As of yet, there are limited studies that focus on the Irish population and so, this topic requires further research and evaluation for quantification of the lapse in diagnostic accuracy and in order to formulate strategies to counter it.

Method: Literature review reference books such as DSM-II, DSM-III, DSM-IV and DSM-5, along with multiple journals and journal repositories like OpenAthens, Google Scholar, PsychInfo, PubMed, BMJ, as well as online resources such as UpToDate, Cambridge University Press, and ADHD Institute.

Discussion: ADHD is a clinical diagnosis with no laboratory test and therefore lends itself to subjective interpretation between individual clinicians. Temporal variation in the diagnostic criteria for ADHD, along with co-morbid conditions such as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and autism spectrum disorder create difficulties in accurate diagnosis.

Over the years the rising rate of ADHD cases is superseded by the almost tripled rate of psychostimulant medication leading to overdiagnosis and over-prescription for ADHD and associated side-effects of each.

Finally the advent of the global Covid-19 pandemic has further limited human interaction leading to delays in appointments, initiation of medication, follow-up visits and optimisation of regimens. All these factors contribute to diagnostic inaccuracies and can potentially result in sub-optimal management of ADHD in children.

Conflict of Interest: Author(s) report no conflict of interest within the scope of this paper.

Introduction

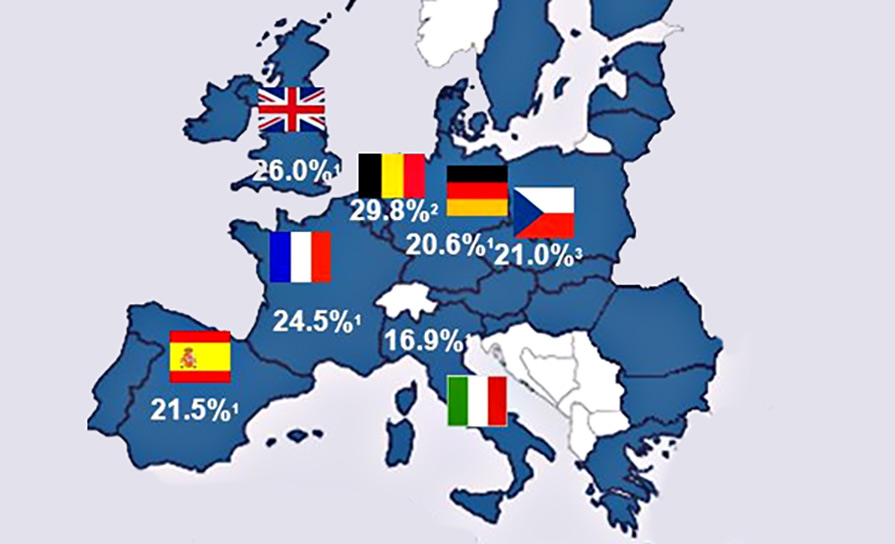

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by the core features of inattentiveness, impulsiveness and hyperactivity. ADHD is a fairly common diagnosable condition in childhood. The ADHD Institute estimates that childhood and adolescent ADHD accounts for up to 8.1 per cent of all psychiatric diagnoses made in the world with a mean prevalence of 2.2 per cent.

Similar numbers have been seen across different cultures and geolocations across the world. As far as the Irish population is concerned, due to a lack of discrete data available, it is impossible to exactly quantify the prevalence of ADHD in Irish children.

The recent census does not adequately distinguish between different forms of disabilities. The 2016 census, however, reports symptoms similar to inattention in 3.3 per cent of the population, with schoolchildren being the largest majority of this percentage.

It is to be noted that because of unavailability of specifically measured data on this specific condition in the specific population under study, the 3.3 per cent reflected in the census must also be taken as a broad categorisation of multiple forms of physical and mental difficulties, among which ADHD is likely to reside, rather than this percentage being the actual quantity of ADHD sufferers in the Irish population.

Risk factors for being diagnosed with ADHD include age, gender (males being affected up to three times more than females), and the presentation of specific symptoms of ADHD. ADHD has far reaching impacts on not just the patient, but also on the parents, caregivers and the broader community in general, because of the requirements and manifestations of a child with diagnosed ADHD as he/she grows up.

Method

Different journals and journal databases were examined for relevant literature on the topic under discussion, such as PubMed, PsychInfo, OpenAthens, the British Medical Journal (BMJ), The Lancet, the Irish health repository Lenus and Google Scholar. In order to expand the search radius, different online resources, such as the official NHS, CDC, Cambridge University Press, UpToDate and the ADHD Institute websites were reviewed using different keywords in order to get a broader view of different trends in diagnosis of ADHD.

The studies, articles and papers referencing and discussing ADHD in children over a time span of 20 years have been included for this review while the resources focusing predominantly on adult ADHD have been excluded from this review article. All included studies and reference materials are in the English language.

Overview of ADHD assessment and management

ADHD is not a new condition. The first clinical description of this kind of symptom constellation dates back to 1902 by George F Still. However, even earlier descriptions exist, which stretch back to the times of the Bible as well.

ADHD is a complex heterogenous and multifactorial entity, which does not have a standard ‘lab test’ per se. The assessment of a child (or adult for that matter) with possible ADHD involves a careful history from the patient or his/her guardians, assessment on different clinically available rating scales such as the ADHD Rating Scale V (ADHD-RS-V) and a meticulous review of the different co-morbid conditions that may be present alongside the primary ADHD, which is often the case in clinical practice.

The DSM-5 has laid down detailed criteria that encompasses the three core features of the condition, ie, inattentiveness, impulsivity and hyperactivity, which is in use today.

The NICE guidelines of 2018 also recommend the ICD-11 criteria for diagnosis of ADHD which, owing to the often-complex presentation of the condition, require that the symptom constellation be observable on two separate occasions in order to be labelled as ADHD. Furthermore, NICE strongly advises that the diagnosis of ADHD be made only by specialist

psychiatrists, paediatricians, and appropriately qualified healthcare personnel in order to guarantee authenticity.

NICE guidelines offer recommendations on the management of ADHD, which involve use of different modalities of treatment, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), parent-training programmes for the guardians involved, and medication such as psychostimulants, eg methylphenidate and lisdexamfetamine.

Medication for ADHD has been a major area of interest not just in terms of efficacy and potential side-effects, but also in terms of rationale. Many clinicians have questioned over the years whether ADHD is being diagnosed (and therefore being treated with medications) accurately or not.

Potential for diagnostic inaccuracy

Many ideas have been postulated as to why ADHD diagnosis may suffer from significant inaccuracy, from social stigma surrounding the condition to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. Some factors of the disease itself also lend themselves to subjective misinterpretation such as:

- Variations in definition;

- Subjectivity of diagnosis;

- Misdiagnosis alongside co-morbid conditions;

- Overdiagnosis and over-prescription;

- Covid-19 and the challenge of ADHD diagnosis.

Variations in definition

As mentioned above, there have been subtle, but clinically important changes made to the definition of ADHD over the years. This is easily observable in the DSM series where the DSM-II first described in detail the symptom constellation of ADHD in 1968, but back then it was termed ‘hyperkinetic reaction of childhood’, and so focused primarily on the hyperactivity portion of the core features.

The term ADHD was introduced in the DSM-III alongside the elimination of ADD with hyperactivity. The DSM-IV further expanded ADHD and described three main subtypes of the condition (predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive, and combined).

The DSM-5 has expanded on each of the defining characteristics of ADHD even further with their A-E criteria. Criterion B, related to the cut-off for the age of onset of symptoms, has been bumped up from seven years to 12 years. Criterion C relating to pervasiveness now only requires evidence of symptoms rather than evidence of impairment. Similarly, Criterion D (impairment) does not require it to be ‘clinically significant’ as long as it ‘reduces the quality of social, academic, and occupational functioning’.

Autism spectrum disorder is also now no longer part of Criterion E (exclusionary diagnoses).

Subjectivity of diagnosis

Because of the complex presentation of ADHD, especially in childhood, many clinicians have to keep a very natural differential diagnosis in their minds, that this presentation may be normal for a child. Dr Tony Lloyd, CEO of the ADHD Foundation, says: “Bear in mind that all children can be forgetful, impulsive, and hyperactive – that’s just how children are.” This presents a challenge when trying to ascertain whether a child’s behaviour is better suited to being labelled as normal but naughty or actual clinical ADHD.

Some clinicians argue that owing to disability benefits, some may be more inclined to declare a child’s normally disruptive behavioural pattern due to social circumstances as ADHD. Tudor Hart has called this a ‘social problem’ rather than a psychiatric one.

Others even argue that ADHD by itself is not a psychiatric condition, but a ‘behavioural construct’. The view a clinician has regarding ADHD is therefore a possible point where diagnostic inaccuracy may be found. The diagnostic criteria reflect this fact in their requirement of multiple observable instances of disease manifestation before labelling it as ADHD.

Irish GPs are often the first point of contact when parents want to get their children evaluated for possible ADHD, and some GPs have mixed views and attitudes about ADHD as a viable medical condition as opposed to a construct. Adamis et al found in their study on GP attitudes and knowledge of ADHD that only a slim majority of GPs harbour a positive attitude towards ADHD and this may lead to many children remaining undiagnosed.

Misdiagnosis alongside co-morbid conditions

A significant portion of diagnosing ADHD includes the concept of looking for co-morbid conditions. It is estimated that as many as 60-to-100 per cent of children with ADHD have some form of co-morbid condition such as oppositional defiant disorder, anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and even disorders involving some degree of cognitive impairment, such as intellectual disability (ID) and autism spectrum disorder.

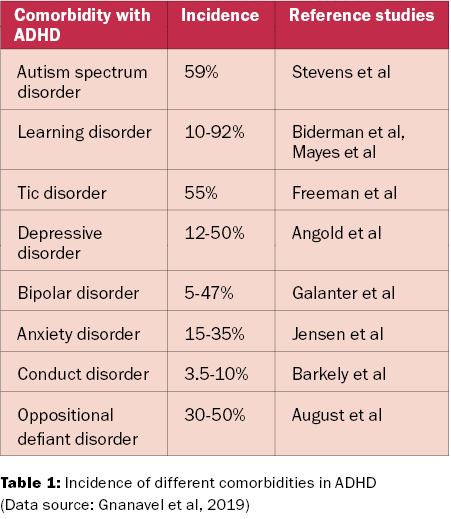

The different co-morbid conditions make the diagnosis of ADHD harder to pin down and this can be a major cause of diagnostic inaccuracy. Table 1 illustrates the prevalence of different co-morbid disorders alongside ADHD. Not limited to the comorbidities in the table, ADHD has been proposed to be present in children with ID as well.

A study was done by Buckley et al in a special school in Ireland looking for prevalence of ADHD among the students enrolled. The Conners’ Teachers Rating Scale was used to screen for ADHD features among children with ID and they were compared with the subscales of the Conners’ Teachers Scale, including hyperactivity, inattention and ADHD index subscales.

It was found that approximately 55.9 per cent of the 84 total participant children showed signs of at least one of each subscale mentioned above; reflecting the possibility of ADHD being undiagnosed in these children owing to their already presenting ID making the ADHD harder to pinpoint.

Similarly, there have been articles about children referred to ‘tic’ clinics who actually had ADHD. One study estimated that 11 per cent of the children coming in to the tic clinics already had ADHD, while 38 per cent of the cases were diagnosed there during the assessment.

What is also interesting is that while NICE guidelines recommend that the diagnosis of ADHD be made by specialist child psychiatrists and paediatricians, 51 per cent of the children referred to the tic clinic were by paediatricians, reflecting the possibility that it may not just be GPs who face difficulty in accurately diagnosing ADHD.

Overdiagnosis and over-prescription

Another possible area of diagnostic error includes children being over diagnosed and therefore being unnecessarily prescribed stimulants. This has been a relatively popular topic among debates on the diagnosis and management of ADHD in medical circles across the globe.

Studies have been done to verify the claims as well. One such study by Beau-Lejdstrom et al was conducted in the UK using ADHD patients under 16 years of age registered in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), to see the trends of drug prescription since 1992 to 2013.

What the researchers found was a 34-fold overall increase in the ADHD drug prescription rate, rising from 1.5 per cent per 10,000 children in 1992 to 51.1 per cent per 10,000 children in 2013, while the rate of ADHD diagnosis increase was only eight-fold. A 2018 review by Lunde et al also found only weak evidence justifying the extensive psychostimulant use today for the management of ADHD.

Another study by MacAvin et al reviewed ADHD medication prescription trends among the child and adolescent population of Ireland from 2005 to 2015. What they found was a significant increase not only in ADHD medication prescriptions for the study population (with males being prescribed three times as frequently as females), but also the co-prescription of concomitant antidepressants.

All the above studies signal a very possible trend of over diagnosing ADHD and thereby overprescribing psychostimulant medication to children. A scoping review is currently underway by Kazda and colleagues to further study this trend in more detail.

Covid-19 and the challenge of ADHD diagnosis

The advent of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has provided a challenging environment for the diagnosis and management of many medical conditions owing to its rapid and sometimes fatal spread among the population. tion-centric condition such as ADHD, Covid-19 has posed difficulties in the diagnosis and optimal management of ADHD. Social distancing and mass lockdowns have limited clinicians’ abilities to gather sufficient evidence to form and make accurate diagnoses.

Some of the key factors outlined in an article in the Cambridge University Press by J McGrath that compose the challenges include, but are not limited to:

Delay in referrals from GPs;

Delay in initiation of medications;

Lack of feedback from schools owing to mass lockdowns;

Difficulty in the assessment of new patients due to lockdowns and social distancing;

Difficulty in optimisation of medications due to limited follow-up.

One study by Merzon et al in the Journal of Addiction Disorders also proposes that untreated ADHD appears to constitute a risk factor in contracting Covid-19, while there was no higher risk in patients with ADHD on treatment.

Conclusion

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder that requires detailed criterion to be met before making a diagnosis. However, due to various factors such as the subjectivity of the diagnosis, variations in the criteria and the definitions of ADHD, viewpoints of clinicians on the validity of the diagnosis, as well as the difficulties imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic, allow for potential misdiagnosis, under diagnosis and overdiagnosis of ADHD in children in Ireland.

Further studies on the topic are required to sufficiently quantify each of the potential factors and thereby address them so as to provide the best possible care for children with ADHD in Ireland.

References on request

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.