An overview of the opportunities and challenges in the field of paediatric urology

Paediatric urology is an often misunderstood and overlooked field of surgery. Paediatric urologists are the custodians of the entire urological and genital systems for both boys and girls, specialising in both the surgical and medical issues related to the kidneys, bladder, and genitalia. Modern-day practices should strive to offer a full range of surgical services spanning the spectrum of acquired and congenital urogenital conditions, including renal transplantation and comprehensive paediatric urological cancer care. Paediatric urological problems may require investigation beyond a clinical visit, as complexities of diagnosis may range from the most simple to the most rare and challenging.

As a result of this, there needs to exist a strong working relationship between paediatric urology and other medical disciplines (ie, feto-maternal medicine, nephrology, oncology, endocrinology, genetics), surgical colleagues (ie, gynaecology, paediatric general surgery, orthopaedic surgery, neurosurgery), and in particular with radiology (diagnostic imaging and image-guided therapy). In managing urogenital conditions, one must take into account the behavioural and psychosocial aspects of each child and each problem. This approach acknowledges the often-sensitive and personal aspects of each patient and his/her problem, allowing for an individualised, patient-centred, culturally-sensitive approach using patient- and family-based care. The history of this juvenile subspecialty, however, is an amalgamation of several specialties, including adult urology, paediatric general surgery and plastic surgery, which has independently found its own pathway for exponential growth.

Early days

Diseases of the genitourinary tract have been recognised for thousands of years. The mummified body of a child, probably at least 5,000 years old and discovered in Egypt, was found to contain a large bladder stone. Circumcision was probably the first surgical procedure ever performed on a regular basis and bladder stones were recognised by Hippocrates. ‘Stone-cutters’, or travelling lithotomists, practised bladder stone removal throughout Europe in the 17th Century. The diarist Samuel Pepys graphically described removal of his bladder stone by a lithotomist and survived the ordeal. However, urology as a specialty in its own right was only instituted in 1890 with the appointment of Félix Guyon in Paris as the first Professor of Urology.

The earliest published works in paediatric urology were as part of treatises written by surgeons who for the most part dealt with all conditions in both adults and children. The Islamic scholars Ar-Razi, Ibn al-Jazzar, Al-Zahrawi and Ibn Sina, who lived within the period of the 9th to the 11th Centuries, were particularly prolific.

Conditions described at this time included urinary retention and different types of anuria, types of renal haematuria, dormant and moving renal stones and their precise localisation, renal or vesical pain, and pain due to colitis. The description of the pathology and the knowledge of new diseases was an important advance made by these scholars. From the urological point of view, spina bifida and its relation to incontinence was first described by Ar-Razi, whereas Ibn Sina was one of the first to point out the psychological role in some cases of nocturnal enuresis.

Thus it remained for the next few hundred years, with surgeons continuing to describe and treat a whole range of urological diseases in both adults and children. The development of paediatric surgery as an independent specialty occurred in the early 20th Century, credited to Sir Denis Browne in the UK, who was appointed as a consultant in Great Ormond Street Hospital in 1928. His contemporaries in the US were William Ladd and Robert Gross (Harvard Medical School; Boston Children’s), the former of whom dedicated his career to paediatric surgery after a naval ship explosion which wiped out half of the city of Halifax in Nova Scotia in 1917.

Development as a distinct subspecialty

However, in order to really discover the contemporary evolution of this “subspecialty”, one has to understand the history of its inception. An offspring of both urology and paediatric surgery, it was born in the post-war years of World War II, but grew faster in the US than it did in the UK/Europe. By 1950, there was in the US a powerful specialist urological association with a widely-spread membership, of whom some developed an interest in childhood disease. In Britain, urology was only recognised by the Royal College as requiring specific training in 1952. By contrast, paediatric surgery was yet to blossom in the UK and would not be in a position to provide a livelihood until national social insurance paved the way from the late 1940s onwards. Following advancements in antibiotic therapy, anaesthesia and medical management of infants, which made surgery for the neonate and sick infant viable, paediatric surgeons took over the management of early childhood thoraco-abdominal emergencies.

Later in the 1950s and early 1960s, disagreements between urologists and paediatric surgeons in the US centred around who should be entrusted to remove Wilms tumours (nephroblastoma). The competition in the UK was more around who had the best five-year survival rates (of course, it would be the development of good oncology units that would ultimately determine this). Textbooks were few and far between. Meredith Campbell had written the initial edition of the now-famed multi-volume encyclopaedia Campbell’s Urology in 1937, followed by further seminal reference works by Sir David Innes Williams and Herbert Johnson that provided advice on the management of both surgical and non-surgical paediatric urology conditions such as Wilms tumours, bladder exstrophy, meningomyelocele, enuresis and recurrent urinary infection, as well as some more passing trends, such as distal urethral stenosis in girls and bladder neck obstruction in boys.

The real breakthrough in the advancement of the specialty came from radiology through the development of intravenous pyelography (IVP) and voiding cystourethrography (VCUG), which allowed physicians to diagnose and manage life-threatening conditions such as posterior urethral valves at a young age. Survival at that time was dependent on early drainage via diversion procedures (ureterostomy/vesicostomy), followed by advancements in nephrological management of the child.

These techniques also led to the discovery of a very high prevalence of vesicoureteric reflux in those who may have urinary tract infections. It was the management of this condition that really put paediatric urology on the global stage, with a number of ureteric reimplant procedures devised to correct it. Little did prior greats in the field such as Sir David Innes Williams realise at that time that these procedures were not always successful, and thus ensued trials in medical management with antibiotics, and the development of the ‘sting’ procedure by Barry O’Donnell and Prem Puri in Dublin. The recognition in the early 1960s that the early pyelographic signs of chronic pyelonephritis were almost always associated with reflux reinforced the support for surgical correction. It was later realised that observation could lead to spontaneous cessation of reflux, which subsequently had a major influence on indications for surgical intervention and the realisation that too many unnecessary operations had been undertaken. The 1980s and early 1990s were dominated by ‘undiversions’ and attempts to reconstruct a representative functional urinary tract following the creation of stomas from earlier decades due to the fear of obstruction having been cognoscente of that particular outcome on renal function.

With the expansion of paediatric surgery as a specialty in its own right in the UK/Europe, there was a much greater proportion of these surgeons who took an interest in urology rather than urologists who subspecialised in paediatrics. There was of course no difference in ability between both pathways. Sir Denis Browne himself was quoted as saying that “the aim of paediatric surgery is to set a standard, not seek a monopoly”. In North America, as paediatric surgery was undertaken as a fellowship after adult general surgery, paediatric urology was more commonly undertaken by urologists. Both pathways brought skills to the arsenal available to the paediatric urologist, including open, laparoscopic, endoscopic, robotic, and transplantation techniques. In the early days, hypospadias surgery was split three ways between paediatric, urological and plastic surgeons, thereby enhancing the scope of appropriate surgery with the introduction of a large variety of approaches and techniques (>200), however this field quickly became subsumed by paediatric urology.

Current challenges

Prenatal hydronephrosis — The advent of regular prenatal screening of mothers in the 1970s and early 1980s led to an exponential rise in the diagnosis of suspected obstructed kidneys, leading to a myriad of renal pelvic reconstructions for ureteropelvic junction obstruction prior to the adoption of conservative and expectant management algorithms. Current screening allows paediatric urologists to counsel expecting parents on differential diagnoses, risk stratification, treatment options, and potential prognoses for a range of congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract.

Transitional urology — This has become an important issue with increases in long-term survival of patients with spina bifida, hydrocephalus, anorectal malformations, and exstrophy complexes, coupled with a steep decrease in infant mortality in the developed world. This is in no small part due to the heroic efforts of paediatric medicine, nephrology, radiology, infectious disease medicine, endocrinology and rehabilitation medicine, as well as nursing and allied health. The challenge to train urologists willing to care for these patients once they graduate from paediatric hospitals has been great and remains a significant issue for not only paediatric urology looking after genitourinary disease, but for other specialties such as cardiology and neurosurgery as well.

Long-term outcomes — There remains a paucity of research on the long-term outcomes of reconstructive techniques, with the overwhelming majority of publications dealing with early success, technique modifications and failure. However, few publish on long-term function, patient-reported outcomes (PRO), cosmesis, psychological impact, or sexual satisfaction/ability. A classic example of this is with the prevalent condition of hypospadias (1:300 boys).

Future challenges

Prospective research and collaboration — It is no surprise that randomised, controlled trials make up <0.1 per cent of all publications in paediatric surgery. This is generally because of the rare nature of these congenital conditions, challenges with consent, and the ethical difficulties in recruiting children for medical trials. The methodological and reporting quality of current systematic reviews/meta-analyses in paediatric urology is concerning (O’Kelly et al, in press), and there is a desperate need for better-quality research to provide evidence for guidelines and policies. In order to achieve this, multidisciplinary approaches to research with data-sharing will be required whilst taking into account research ethics, privacy and data-sharing rules.

Centralisation of complex, rare disorders — The UK has been in a position to lead the way on super-specialisation and regionalisation of complex care in urology in a way that would not be possible in the US with a multi-payer system. In urology, penile cancer and advanced testis cancer have been centralised, with a similar model for paediatric surgery with centralisation of hepatobiliary management and bladder exstrophy surgery. The latter had been proposed by Sir David Innes Williams nearly 50 years ago and has led to an improvement in exposure, outcomes, and research volume. The obstacles to this approach are transportation difficulties for patients and families in certain parts of the world, the potential financial interest of individual surgeons, and, last but not least, surgeons’ reluctance. It is also unknown in many cases how many procedures are required to maintain annual competence. Much of reconstruction is a hybrid of a number of techniques applied to a particular condition. Paediatric urologists may already perform a number of these on a regular basis, but are then being asked not to perform them together for specific cases, and to instead refer these on. A cleaner model for proof of principle lies in hypospadiology, where there is currently a smaller number of techniques and metrics for a much more common condition. It is now felt by some experts in the field that an adequate number of procedures per year to deal with complications and variations is approximately 60 and that proximal hypospadias should only be performed by two experienced hypospadiologists working together (W Snodgrass; personal communication).

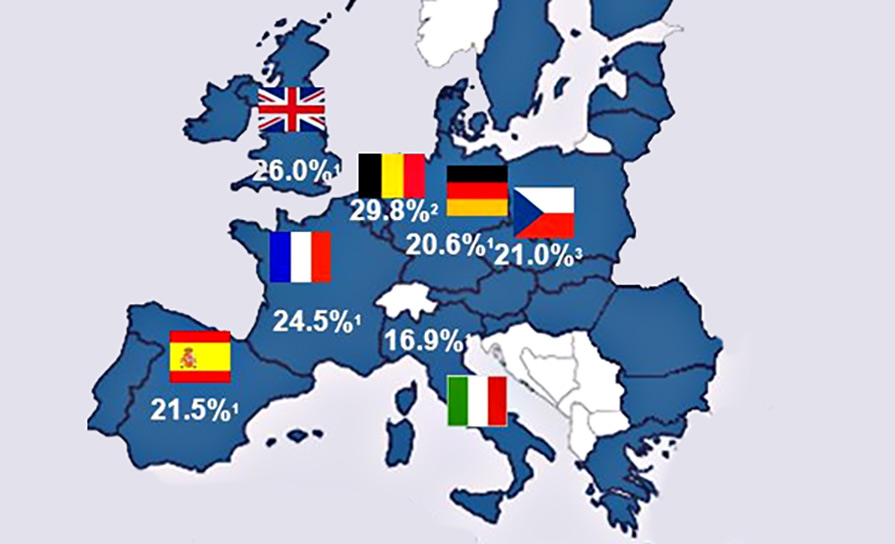

Training — Advances have been made in many countries formalising the training requirements for future specialists. Different approaches have been taken in the US, Canada, and in Europe. In the US and Canada, opportunities for specialised training are limited to those who have completed training in general urology or adult general urology and a prior fellowship in paediatric surgery.

Progress in Europe has enabled both urologists and paediatric surgeons to pursue advanced training in paediatric urology, increasing the number and spectrum of potential trainees. Despite this, the number of trainees who pursue a fellowship in paediatric urology remains low (<2 per cent all trainee numbers, potentially due to exposure during residency training), and recruitment of paediatric urology fellowship-trained consultants remains a significant issue.

Furthermore, both the US and Canada have now introduced sub-speciality board-approved certificates of focused competence in paediatric urology in an attempt to gain further independence from general urology.

Another challenge for training paediatric urologists to treat rare congenital anomalies is the relatively small number of complex cases at most institutions as a result of high numbers of centres (North America), decreasing birth rates, and incidence of major malformations (in part from termination). Therefore, setting-up training collaborations with large-volume centres in countries with large populations and greater incidence of birth defects may be a solution to the problem. This, however, must be performed in conjunction with local team training to strive for a sustainable model of care yielding greater benefits to all parties on a more permanent basis.

Isolated examples of this model exist in places like Ethiopia, Rwanda and Pakistan (P Ransley, personal communication). A further approach to provide specific training within rare congenital malformations is the creation of regional centres of expertise to which patients are referred, thus creating teams of expert teachers in one particular malformation.

The evolving role of the paediatric urologist

This has been largely determined by geography and the effect of different healthcare systems on the expectations and realities of this position. Initially in both Europe and (to a lesser extent) North America, paediatric urologists were attached to large academic medical referral centres and carried out complex surgical reconstruction.

With an increase in numbers and an expansion of the portfolio to include not just surgical procedures, but research and a complex understanding of medical urology, they became involved in the management of recurrent UTIs, enuresis (bedwetting), and non-neuropathic voiding disorders, such as bladder bowel dysfunction. Indeed, some lamented the loss of the role of a pure genitourinary surgeon, as paediatric urologists became more holistic and all-encompassing in their care. These non-surgical conditions which had originally been in the domain of the paediatrician began to fill outpatient clinics, leaving less time to see ‘surgical’ cases, and so an attempt to address this was made by triaging these cases away from tertiary referral centres, with concomitant concerns over surgical skills and training. This pattern soon repeated itself with more common problems such as phimosis, undescended testes, and patent processus vaginalis (communicating hydrocoele; indirect inguinal hernia), and thus the model of these conditions being seen by non-tertiary referral physicians came to fruition. It should also be noted that in many cases, the ability of surgeons to effectively deal with these cases was largely dependent on the comfort of anaesthesiology colleagues with paediatric patients and the local resources/staff expertise available.

The contemporary paediatric urologist is required to have total commitment to the specialty, with international guidelines suggesting a ratio of 1:1,000,000 of the population. They work as part of a multidisciplinary approach to treat congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract, hypospadias, genitourinary oncology, transplantation, complex pelvic floor disorders, anorectal malformations, exstrophy complexes, paediatric stone disease and disorders of sexual differentiation, to name but a few. They will continue to treat more common problems, as well as see non-operative issues. There will be a greater role for the establishment of multidisciplinary transgender clinics and transitional care, as well as embracing modern initiatives of telehealth and quality improvement.

From an Irish perspective, there is a significant shortage of paediatric urologists within the country, and recruitment of consultants who have undertaken specific fellowships in paediatric urology within high-volume centres remains a challenge in the current climate. They play an important role as custodians of the urinary tract and genitalia of both boys and girls, which continues into adulthood and beyond.

Limitations to access or resources can lead to a loss of renal function, loss of genital and sexual function, infertility, higher rates of urological cancers, increased levels of morbidity, psychological disorders and even death. It is therefore clearly imperative to ensure the appropriate numbers of these specialists for the population.

References on request

New model of care for urology proposes radical change in delivery of urological care in Ireland

Priscilla Lynch

A model of care for the treatment of urological conditions in Ireland was launched recently by Mr Kenneth Mealy, RCSI President, at Roscommon University Hospital (RUH). Developed by RCSI in partnership with HSE Acute Operations and the National Clinical Programme in Surgery (NCPS), ‘Urology: A model of care for Ireland’ outlines a radical change in the delivery of urology care so that the majority of urology patients will be cared for in the community.

The model of care envisages a system of urology care that serves the majority of patients in the community, in primary care centres or in their local hospital, while assuring appropriate clinical governance to support a safe and high-quality service.

RUH is the primary pilot site for a One Stop Rapid Access Haematuria Pathway (RAHP) clinic providing access to diagnostics for patients who have symptoms of haematuria with procedures and investigations carried out within 28 days. The RAHP clinics are one of the key improvement initiatives within this model of care

Mr Eamonn Rogers, the NCPS Clinical Advisor in Urology, was commissioned by the HSE to undertake this work. Speaking ahead of the launch, Mr Rogers pointed out that as the frequency of urinary symptoms and pathology increases with age, Ireland’s changing demographics mean that a radical reconsideration of how best to deliver urology services is necessary: “This model of care must be implemented in full so that we can deliver an efficient and economically viable service which improves the access of patients across Ireland to the services they require as they get older, delivered by a range of healthcare providers including general practitioners, physiotherapists, and clinical nurse specialists, advanced nurse practitioners, physician associates and urologists.”

Welcoming the publication of the model of care, Dr Vida Hamilton, National Clinical Advisor and Group Lead, HSE Acute Operations (NCAGL), said it was developed in collaboration with a wide range of stakeholders and outlines an integrated and multidisciplinary approach to urology services: “Its publication is welcomed and its implementation will improve services and patient outcomes”.

Prof Deborah McNamara, Co-Lead of the National Clinical Programme in Surgery (NCPS) said: “The development of specialty models of care is the next step in defining best practice. It allows a deeper understanding of the range of activity delivered by specialist services and of areas where there are unmet needs. It is also an opportunity for each specialty in surgery to define how the multidisciplinary surgical workforce can best deliver the care required by Irish patients, taking into consideration the new ways of working that are now the standard of care. Improvement of surgical services will require specialties to consider new ways of working, including the migration of some procedures towards ambulatory treatment instead of inpatient care.”

She said new technology has the potential to change not only the diagnostic and therapeutic procedures that can be performed, but also the way that surgeons communicate with patients, interdisciplinary team members, colleagues in the community and their fellow surgeons. “The starting point for the development of specialty models of care must remain the needs of Irish patients and our responsibility to ensure that these services are accessible, safe, equitable and of high quality”, added Prof McNamara.

According to Prof John Hyland, Co-Lead National Clinical Programme in Surgery “Implementation of this model of care and its nineteen recommendations will be critical to enable every urology patient to benefit from quality improvement in all aspects of their healthcare journey.”

The NCPS is an initiative of the HSE and RCSI. An important role of NCPS is defining the standards of care that should apply to surgical care in Irish hospitals. The NCPS has previously published models of care for Acute Surgery, Elective Surgery, and Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery.

Urology: A model of care for Ireland is available for download at: http://rcsi.ie/files/surgery/docs/20190904092141_Specialty Models of Care Urolo.pdfnormal.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.