Malnutrition, sarcopaenia and frailty are highly prevalent in cirrhosis, relate to multiple mechanisms, and are associated

with worse clinical outcomes

Nutrition has an imperative role in maintaining health. The annual cost associated with disease-related malnutrition among patients in Ireland was estimated at €1.4 billion or 10 per cent of the total healthcare budget in 2012. Furthermore, complications of disease-related malnutrition among hospitalised inpatients and those in residential healthcare settings was responsible for the majority of this spend (Rice et al, 2012). The HSE published the National Clinical Guideline No 22 in April 2020 mandating that all hospital inpatients in Ireland should be screened for nutritional status and risk of malnutrition on admission.

It is estimated that by following these guidelines, over 30,000 bed days with net savings of €24 million per year could be saved (local budget impact analysis 2020).

The liver plays a significant role in the digestion, absorption, storage, synthesis and metabolism of different nutrients; in simple terms, the liver is the body’s energy factory. In the presence of cirrhosis due to severe liver damage of varying aetiology, these functions of the liver become severely impaired.

Impaired nutrition in patients with cirrhosis is well recognised; patients with decompensated cirrhosis often have typical features of poor nutrition, such as anorexia, muscle wasting and diminished strength, thin skin and easy bruising, ascites and fluid overload. The prevalence of malnutrition in patients with cirrhosis varies from 20-to-50 per cent, although malnutrition may be less apparent in patients with compensated cirrhosis.

Although the term malnutrition typically refers to undernutrition, obesity is increasingly observed as an important contributor to advanced liver disease. Metabolism associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), or non-alcohol fatty liver disease (NAFLD), has become the leading cause of chronic liver disease in Western societies, and is the hepatic manifestation of the obesity pandemic. Moreover, adolescent obesity has been associated with a remarkably higher risk of developing severe liver disease later in life.

Despite obesity, patients with advanced liver disease due to MAFLD can often have concomitant reduced muscle mass, referred to as sarcopaenic obesity.

Sarcopaenia is defined as a generalised reduction in muscle mass, strength and function due to ageing (primary sarcopaenia), acute or chronic illness (secondary sarcopaenia), such as chronic liver disease. Frailty may be defined as loss of functional, cognitive, and physiologic reserve leading to a vulnerable state. Sarcopaenia and frailty are considered nutrition-related disorders, and are often representative of severe malnutrition, with approximately 80 per cent of malnourished older patients having concurrent sarcopaenia; (though conversely, only about 20 per cent of sarcopaenic patients are malnourished (Gingrich et al, BMC Geriatrics 2019).

Studies estimate the global prevalence of sarcopaenia in cirrhosis is around 48 per cent, and more common in men (62 percent) than in women (36 per cent). Among patients with cirrhosis in the ambulatory setting, prevalence of frailty varies from 17- to-68 per cent. Both sarcopaenia and frailty are well recognised as predictors of morbidity and mortality in patients with cirrhosis. The implications of these conditions are a poor quality-of-life, worse outcomes, and shorter survival.

Pathogenesis of malnutrition, sarcopaenia and frailty in cirrhosis

The pathogenesis of protein energy malnutrition, sarcopaenia and frailty in patients with cirrhosis is multifactorial, reflecting an imbalance between caloric intake and requirements, and muscle formation and muscle degradation, engendered by the factors driving liver injury and also the liver dysfunction itself.

Some of the common reasons include:

Dietary intake may be limited by alcohol dependence, hepatic encephalopathy, nausea, vomiting or early satiety due

to ascites, and reduced food palatability due to a low salt diet.

Maldigestion and malabsorption can be caused by bile acid deficiency due to decrease in synthesis and reabsorption and a consequent smaller bile acid pool, portal hypertensive enteropathy, intestinal dysmotility, disturbance of the gut microbiome or alcohol-related chronic pancreatitis.

An imbalance between caloric intake and requirements occurs commonly in patients with cirrhosis leading to a hypermetabolic, catabolic state.

Advanced liver disease often reflects a heightened inflammatory state, evidenced by an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines which lead to the destruction of myocytes and degradation of muscle tissue. Inflammation impairs the ability

of the liver to store and utilise glycogen, which leads to an increase in gluconeogenesis from protein and fat breakdown.

Similarly, cirrhotic patients have immune dysfunction, resulting in increased rates of infection along with translocation of bacteria and bacterial particles from the gut, further contributing to chronic inflammation.

Hyperammonaemia occurs variably in patients with cirrhosis. As a toxin, ammonia must be detoxified to prevent muscle damage; this may be through branched chain amino acids (BCAA) which convert ammonia to glutamine. BCAA deficiency in liver cirrhosis is common and may be related to consumption in skeletal muscle. Muscle breakdown leads to increased ammonia and other toxins, which propagate hepatic encephalopathy.

Hormonal imbalances, such as deficien growth hormone, testosterone and cortisol are seen in cirrhosis patients and contribute to the development of sarcopaenia. Alcohol consumption has a direct effect on muscle tissue and will lead to reduced muscle mass and impaired muscle function.

Nutritional assessment and screening

Malnutrition, sarcopaenia and frailty are common complications of cirrhosis, which are often not assessed in routine clinical practice. Body weight and body mass index (BMI) are affected by fluid retention from ascites and oedema, which may result in underreporting of malnutrition. The Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) has

been recommended as the screening tool of choice by different societies and is currently used in many Irish hospitals.

However, this incorporates BMI and unplanned weight loss, which are inaccurate in the presence of ascites or fluid retention. Recognising this, alternative nutritional assessment tools have been developed for cirrhotic patients.

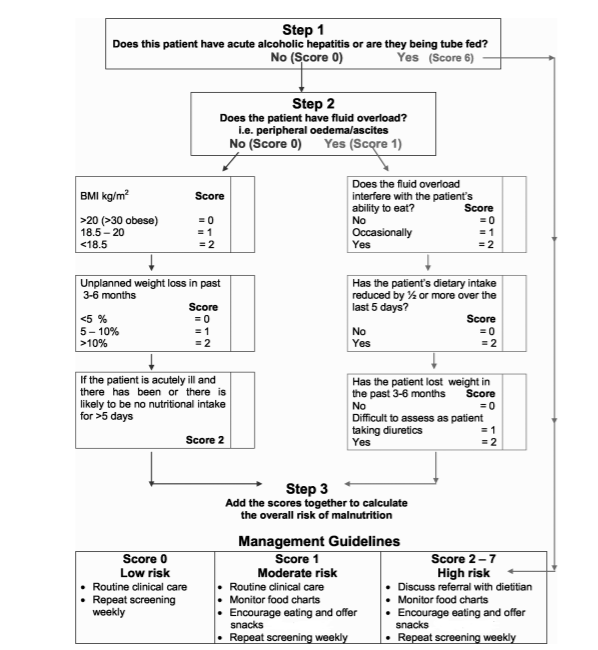

Of these, the Royal Free Hospital-Nutrition Prioritising Tool (RFH-NPT) has been most consistently associated with a diagnosis of malnutrition (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Royal Free Hospital-Nutritional Prioritising Tool (RFH-NPT). Source: Amodio P

et al, Hepatology, July 2013

Patients are classified into three nutritional risk categories (low, moderate, and high) based on a combination of (1) presence of acute hepatitis or need for enteral nutritional support; (2) low BMI, unexplained weight loss, maintenance of volitional nutritional intake; and (3) whether fluid overload interferes with ability to eat.

Patients identified as high risk for malnutrition according to the RFH-NPT classification have been shown to experience poor clinical outcomes, including reduced survival, lower quality-of-life and worsened liver function. Improvement in the RFH-NPT has been associated with improved survival. The recognition and diagnosis of sarcopaenic obesity is important. A large epidemiologic study from the UK including 1.3 million women found the risk of cirrhosis was

increased by almost six times in women who were heavy drinkers and obese, compared with non-drinkers, and twice as high as heavy drinkers alone. Furthermore, a large retrospective UNOS (United Network for Organ Sharing) database analysis has shown higher liver transplantation waitlist mortality in morbidly obese cirrhosis patients.

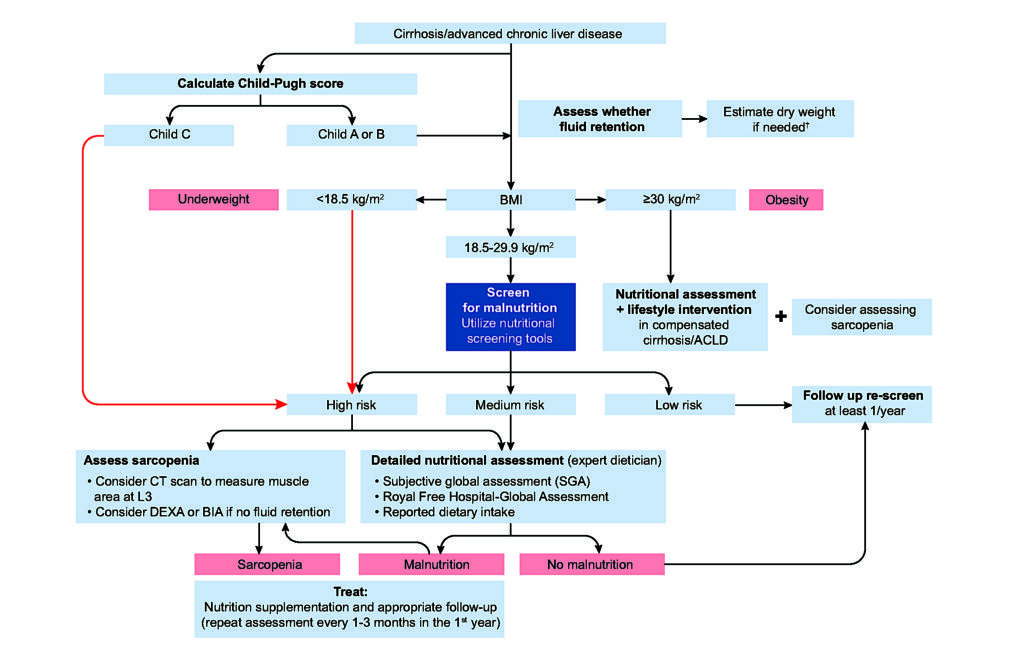

Studies have shown a correlation of severity and prevalence of sarcopaenia in cirrhosis with the Child-Pugh score, a commonly used measure of liver disease severity. This score is recommended as the first step in the approach to assessing nutritional status in patients with cirrhosis (European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL),

Clinical Practice Guidelines on Nutrition in Chronic Liver Disease, Figure 2). The ChildPugh score is a composite score combining clinical features of cirrhosis-ascites and encephalopathy, with blood markers of liver function – bilirubin, prothrombin time, and albumin. It divides patients in three categories: (A) compensated cirrhosis; (B) moderate hepatic dysfunction; and (C) advanced hepatic dysfunction.

High risk patients (those with a low BMI [<18.5kg/m2 ] or high BMI [>40kg/m2 ] and Child-Pugh C patients) do not require nutritional risk stratification screening as they clearly need intervention. Nutritional screening is recommended in all other patients with cirrhosis (Figure 2).

Nutritional management in cirrhosis

Nutritional status plays a crucial role in the survival and recovery of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. It is important that patients consume an adequate amount of energy and protein to minimise the risk of developing a catabolic state.

Patients must adapt their meal pattern during the day so that prolonged fasting is avoided. Small, frequent (four to six) portions of nutritionally dense foods per day are recommended. Overnight fasting in cirrhotic patient leads to increased fat oxidation and gluconeogenesis, toxin production and encephalopathy; early morning breakfast and late evening snacks containing carbohydrates are therefore recommended.

Concern regarding high protein intake worsening hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis has not been replicated in recent studies. Similarly, protein restriction has been shown not to prevent or worsen hepatic encephalopathy. As cirrhosis is a catabolic state, protein restriction will promote muscle degradation, while increased protein intake will provide amino acids for gluconeogenesis and buffer ammonia from the blood stream.

An adequate diet should provide at least 30-to-35kcal/kg(dry-body-weight)/ day. Healthy individuals require around 0.66gram/kg of protein every day. In patients with cirrhosis without malnutrition, the daily protein requirement increases to 1.2gram/kg and this increases even further to 1.5gram/kg in presence of malnutrition. Patients with intolerance to protein can be prescribed branched-chain amino acid supplementation to meet their protein intake requirements.

Total calorie intake should be consistent of 50-to-60 per cent carbohydrates and 20- to-30 per cent fat. Complex carbohydrates (starches) found in foods such as peas, beans, whole grains, and vegetables are desirable. Saturated fatty acid should not be consumed as more than 10 per cent of total calories, while monounsaturated fatty acids and polyunsaturated fatty acids should contribute equally to the remaining portion of calories provided by fats.

Patients with obesity and cirrhosis are given a target weight reduction of 5-to10 per cent. To achieve this goal, patients

should increase their total energy expenditure by 500-to-800kcal/day. However, this should be achieved with adequate protein intake (1.2-1.5gram/kg (ideal body weight)/ day), accompanied by exercise adjusted to the patient’s ability.

Vitamins and minerals

Patients with liver cirrhosis are at risk of micronutrient and vitamin deficiencies. Deficiencies in fat-soluble vitamins (vitamin A, D, E, and K) are common in patients with advanced cirrhosis, and are especially prevalent in patients with cholestatic liver disease. Vitamin D deficiency has been repeatedly associated with worse outcomes in patients with chronic liver disease and serum levels should be assessed regularly. Oral vitamin D supplementation should be commenced when serum levels are <50ng/ ml, as per local guidelines.

Water-soluble vitamins, particularly thiamine (vitamin B1), are frequently deficient in patients with cirrhosis, in particular, those with alcohol dependence or severe malnutrition. High caloric food or glucose administration prior to thiamine administration can precipitate Wernicke’s encephalopathy (particularly in the context of alcohol dependence). Cobalamin (vitamin B12) and folate (B9) are required to make normal red blood cells, white blood cells, repair tissues

and cells, and synthesise DNA. Vitamin B12 is also important for normal nerve cell function.

As they are stored in the liver, cirrhosis leads to decreased storage capacity, and an associated increased risk of B-vitamin deficiencies. Multivitamin supplementation is an easy and cost-effective way to supplement any specific deficiency.

Mineral deficiencies are also seen in cirrhosis. Magnesium deficiency is associated with muscle cramps, reduced muscle

strength, and cognitive impairment, particularly with alcohol dependence. Hyponatraemia may be caused by decompensated liver disease with hyperaldosteronism and excess ADH production, diuretic intolerance or alcohol. It is crucial that increased salt intake is not advised as the solution.

If anything, excessive salt in patients with advanced cirrhosis will lead to persistent or worsening of dilutional hyponatraemia, ascites and peripheral oedema. The recommended daily sodium intake should be 2g of sodium, which is equivalent to 5g of salt.

In order to convert sodium to salt, patients can simply multiply the labelled sodium amount by a factor of 2.5. Foods that have a high salt content should be avoided. These include snacks such as crisps, nuts, processed deli meats, smoked meat and fish, tinned foods, shop-bought sauces, stock cubes, gravy, soups, condiments, and ready meals. In

a study of 120 outpatients with cirrhosis and ascites, only 31 per cent were adherent to a 2g sodium diet, and adherent patients had a 20 per cent lower daily caloric intake. It was found that low salt diet could lead to unpalatable food and potentially decrease energy intake by patients. This indicates importance of dietician involvement in the multidisciplinary care of patients with cirrhosis

In summary

In summary, malnutrition, sarcopaenia and frailty are highly prevalent in cirrhosis, relate to multiple mechanisms, and are associated with worse clinical outcomes. Prompt and repeated screening for these conditions, along with the initiation of evidence-based, specialist-led dietary interventions can have a positive impact on the quality-of-life and prognosis of patients with advanced liver disease and are a cost-effective means to counteract disease-related

malnutrition in this vulnerable population.

References on request

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.