An overview of the presentation, diagnosis, and management of UTIs in women

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most prevalent bacterial infections encountered in clinical practice. They primarily affect the urinary system, including the bladder, urethra, ureters, and kidneys. UTIs can manifest as uncomplicated or complicated infections, with varying degrees of severity and associated complications.

Uncomplicated UTIs, also known as cystitis or lower UTIs, are bacterial infections of the bladder and associated structures, and usually occur in non-pregnant females with no structural abnormality or comorbidities. A UTI is considered complicated if it affects the upper urinary tract, children, pregnant women, or the elderly, and can occur in patients with structural abnormalities or comorbidities such as diabetes or immunocompromised status.

Up to 40 per cent of women develop a UTI at some point in their life compared to 12 per cent in men. Anatomically, the female urethra is shorter and located closer to the anus than in males, which makes it easier for bacteria to reach the female urethra and bladder. Adult women are 30 times more likely than men to develop a UTI, with almost half of them experiencing at least one episode during their lifetime, and one-in-three women experiencing a first episode by age 24.

Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria from the gut is the cause of 80-to-85 per cent of community-acquired UTIs, with Staphylococcus saprophyticus the cause in 5-to-10 per cent. Occasionally, UTIs may also be caused by viral or fungal infections. Healthcare-associated UTIs are mostly related to urinary catheterisation, and involve a much broader range of pathogens.

UTIs are most commonly seen in sexually-active young women. Sex can irritate and weaken the female urethra, making it easier for bacteria to enter. Certain contraceptives, including the diaphragm and spermicide-coated condoms, can also increase a woman’s risk of developing UTIs.

Other susceptible women include the elderly and those requiring urethral catheterisation. Urinary tract symptoms are not always obvious in the elderly. Presentation may be vague with incontinence, change in mental status, or fatigue as the only symptoms, while some patients present with sepsis as the first symptoms. Diagnosis can be complicated by the fact that many older people may already have pre-existing incontinence or dementia.

Other risk factors for developing UTIs include conditions that prevent fully emptying the bladder, kidney stones, a weakened immune system, undergoing chemotherapy, and diabetes. The presence of bacteria in urine does not always depict a UTI. Some people, especially older people in residential care/nursing home facilities, can have bacteria in their urine without having any ill effects. This is known as asymptomatic bacteriuria. Antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent UTIs should not be used routinely in older people in residential long-term care facilities. Residents in long-term care facilities have high rates of abnormal dipstick and urine test results without infection necessarily being present.

Antibiotic therapy in these cases does not reduce mortality or prevent symptomatic episodes, rather it increases side-effects and leads to antibiotic resistance.

Pathology

UTIs typically occur due to the colonisation of uropathogenic bacteria in the urinary tract. E. coli is the most common pathogen responsible for overall UTIs, although other microorganisms such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, and Staphylococcus saprophyticus can also cause infections. Adherence to the uroepithelial cells, invasion of the mucosa, and subsequent inflammatory responses contribute to the pathogenesis of UTIs. The pathology of UTIs involves a complex interplay between uropathogenic bacteria and the host’s immune response. Bacterial adherence to the uroepithelial cells lining the urinary tract is the main step in establishing infection.

The invasion and colonisation of uropathogenic bacteria also triggers an inflammatory response in the urinary tract. Various host factors can influence susceptibility to UTIs, including genetic predisposition, hormonal fluctuations, and underlying comorbidities.

Symptoms

Symptoms of a lower UTI include dysuria, frequency, and the urge to urinate despite having an empty bladder. Symptoms may also include cloudy and unpleasant smelling urine, haematuria, abdominal pain, pelvic tenderness, back pain, and a general sense of feeling unwell.

Symptoms of a kidney infection include fever of <38°C (100.4°F), shivering, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and flank pain. In addition, frequency, dysuria, urgency, and haematuria may also be present.

Diagnosis

Urinalysis reagent strips are the most frequently used tools for diagnostic testing if there is clinical evidence that a patient has a UTI. In patients with symptoms, a negative dipstick does not rule out a UTI, but positive findings can suggest and help make the diagnosis.

A high number of leucocytes in the urine points to the presence of white blood cells, indicating inflammation or infection along the urinary tract, often in the bladder or kidney. The presence of nitrites in the urine is highly specific to certain bacterial infections, but nitrites do not occur with all types of bacteria. E. coli bacteria are most commonly associated with nitrites in the urine. An infection may occur in the presence of leucocytes with no nitrites, however, leucocytes in the urine without nitrites can also lead to a false-positive result that points to a bacterial infection when there is none. Negative nitrite and negative leucocyte have a 95 per cent negative predictive value.

A positive nitrite test is more indicative than a positive leucocyte test, although the presence of both increases the possibility of a UTI diagnosis. For most woman with typical symptoms of a lower UTI, further testing is not usually required to confirm the diagnosis.

Circumstances where laboratory testing is recommended include:

- Cases of a suspected upper UTI.

These infections have a higher risk of complications, so a careful assessment of the state of the urinary tract needs to be made.

- UTIs that occur in pregnant women due to the higher risk of developing complications.

- In cases where a woman has blood in their urine. Although unlikely, this could be a symptom of bladder cancer, so it is important to rule out or confirm the diagnosis.

- In cases where a woman has a risk factor that makes them more vulnerable to developing serious complications, such as having a weakened immune system.

Other diagnostic tests required may include ultrasound, CT scan, MRI, or cystoscopy.

Treatment

Choice of empirical therapy should be governed by local resistance rates where available, and patterns can vary substantially across the country. HSE prescribing guidelines for urinary infections are available here: www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/2/gp/antibiotic-prescribing/conditions-and-treatments/urinary/. See Tables 1, 2, and 3.

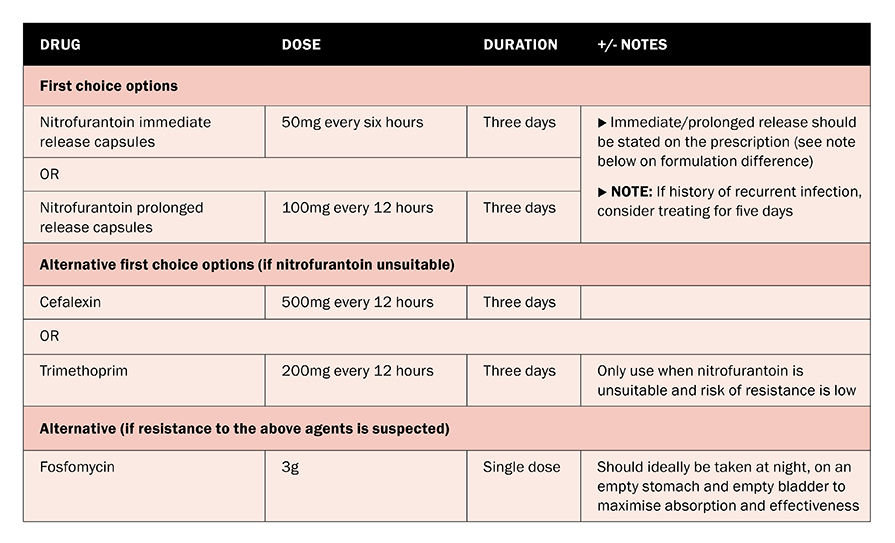

TABLE 1: Uncomplicated UTI treatment in non-pregnant adult females under 65 (HSE)

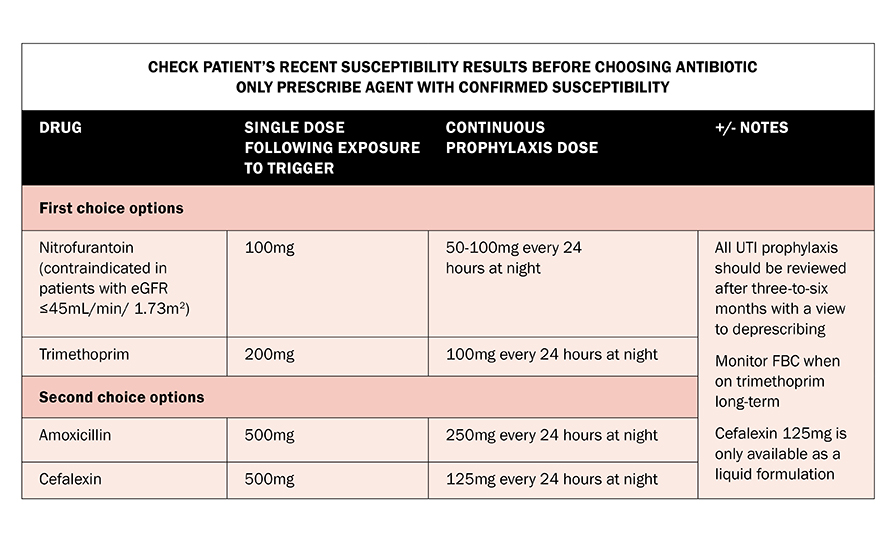

TABLE 2: Recurrent UTI treatment in adult non-pregnant females (HSE)

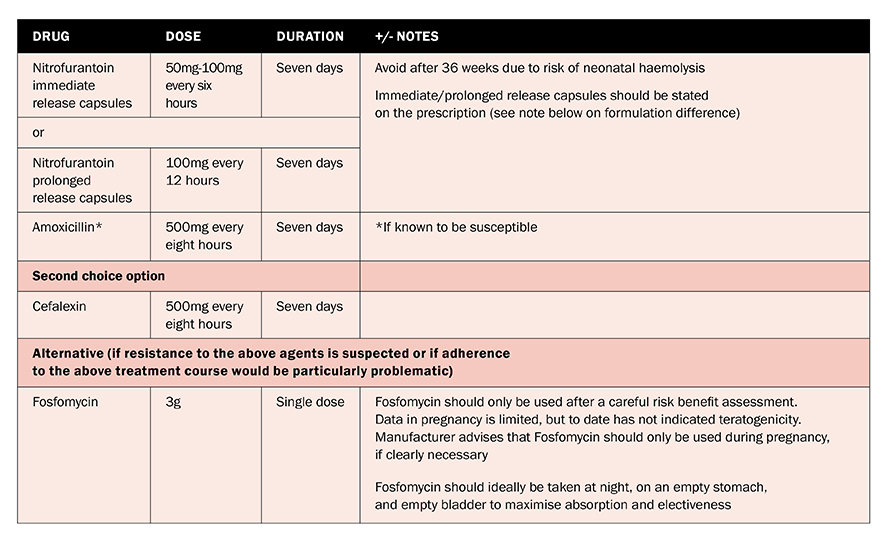

TABLE 3: Lower UTI treatment in pregnancy (HSE)

Nitrofurantoin is the first-choice antibiotic if it is not contraindicated. Nitrofurantoin resistance rates remain low in community E. coli UTIs throughout Ireland, including in extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing isolates, despite increasing resistance to other antibiotics. Nitrofurantoin concentrates well in the bladder, but is only suitable for uncomplicated lower UTIs. It should not be used in patients with severe renal impairment, but may be used with caution as short-course therapy only if there is a lower degree of renal impairment (eGFR greater than 30mL/min) to treat suspected or proven resistant pathogens, when the benefits are expected to outweigh the risks.

Two nitrofurantoin formulations are available: Nitrofurantoin immediate release capsules (Macrodantin), and nitrofurantoin prolonged release capsules (MacroBid).

For the treatment of infection, prolonged release capsules are dosed twice daily whilst the standard capsules are dosed four times daily. Nitrofurantoin is not a suitable antibiotic choice in pyelonephritis.

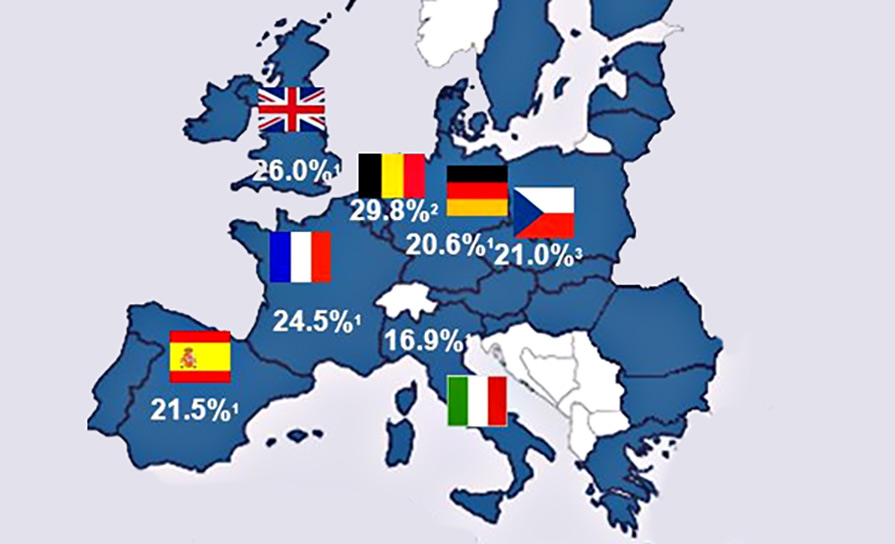

Trimethoprim resistance in community E. coli UTIs exceeds 30 per cent across Ireland. Empiric trimethoprim is no longer recommended, except where nitrofurantoin is unsuitable and the risk of resistance is low.

Cefalexin is a broad-spectrum systemic agent and should be avoided in uncomplicated UTIs, unless there is no suitable alternative, to prevent the emergence of resistant organisms and Clostridium difficile (C. diff) infection.

Amoxicillin is not recommended as empiric therapy, as resistance rates of approximately 60 per cent in community E. coli UTIs have been described in recent Irish studies. Therefore, it is only suitable for use if susceptibilities

are available.

Co-amoxiclav resistance is also increasing in Ireland. In addition, it is a systemic agent and should be avoided in uncomplicated cystitis if a locally-acting agent, such as nitrofurantoin, could be used instead.

Ciprofloxacin is a broad-spectrum systemic agent associated with C. diff infection and multiple adverse effects. It is not recommended for the empiric treatment of uncomplicated cystitis. It may be considered for targeted therapy of multi-resistant infections where there are no other appropriate options.

Recurrent UTI in adult non-pregnant females

In non-pregnant females with recurrent lower UTI, non-antimicrobial measures prior to antimicrobial prophylaxis should be attempted. Behavioural measures which may help reduce the risk of recurrent UTI include:

- Increased fluid intake;

- Avoid the use of potential irritants such as soaps, perfumes, talcs, cleansing wipes,

- disinfectants in the area;

- Advise woman not to wash the genital area too often, once a day is usually enough;

- Use an emollient-based product or plain warm water

to wash;

- Consider a barrier cream or ointment in incontinence;

- Advise post-coital voiding;

- Do not habitually delay urination;

- Avoid constipation;

- Wipe from front to back after defecation;

- Consider vaginal oestrogen in postmenopausal women.

Antimicrobial prophylaxis, either single dose (such as post-coital) or continuous, can be effective and should be considered if non-antimicrobial measures are unsuccessful. However, the side-effects of antibiotic prophylaxis should also be considered. All antibiotics are associated with a risk of C. diff infection. Long-term nitrofurantoin use is associated with multiple adverse effects, including liver damage, pulmonary fibrosis, and peripheral neuropathy. Patients on long-term nitrofurantoin should be monitored closely for these conditions and treatment should be withdrawn if they emerge.

When a trial of antimicrobial prophylaxis is given, advise the patient regarding the risk of resistance with long-term antibiotics; the possible adverse effects of long-term antibiotics; and the need to seek medical help if symptoms of an upper UTI develop. All UTI antimicrobial prophylaxis should be reviewed after three-to-six months with a view to deprescribing.

There is limited evidence of any additional benefit from such prophylaxis beyond this period, but there is significant evidence of harm.

Lower UTI in pregnancy

Nitrofurantion should be avoided after 36 weeks’ gestation due to risk of neonatal haemolysis. Trimethoprim should not be prescribed for pregnant women with established folate deficiency, low dietary folate intake, or women taking other folate antagonists. If acute pyelonephritis is suspected, referral to hospital should be considered.

Acute pyelonephritis/upper UTI should be considered when there is pain in the loin that radiates to the iliac fossa and suprapubic area; sudden onset of general systemic disturbance with fever; rigors; vomiting; or tenderness and guarding over the kidney.

Acute pyelonephritis

An MSU should be sent for culture and sensitivity in all cases of acute pyelonephritis prior to the patient starting the antibiotic. Acute pyelonephritis/upper UTI should be considered when:

- Pain in the loin radiates to the iliac fossa and suprapubic area;

- Sudden onset general systemic disturbance with fever, rigors, vomiting;

- Tenderness and guarding over the kidney.

Consider referring to hospital if:

- Patient is significantly dehydrated or unable to take oral fluids and medicines;

- Child/young person <16 with acute pyelonephritis;

- Aged 16 years and over with acute pyelonephritis and has a severe systemic infection;

- Patient is pregnant;

- Patient has at higher risk of developing complications, such as patients with known or suspected structural or functional abnormality of the genitourinary tract, or underlying disease such as diabetes or immunosuppression.

Conclusion

The increasing prevalence of antibiotic resistance among uropathogens presents a major challenge to the clinical management of UTIs. Appropriate empirical treatment of UTIs is important for successful treatment and prevention of complications. However, with the increasing prevalence of antibiotic-resistant urinary pathogens, the selection of an appropriate empirical agent is increasingly difficult.

Resources

- HSE. Urinary tract infection. Health Service Executive. 2021. Available at: www2.hse.ie/conditions/urinary-tract-infections-uti/html

- HSE. Urinary Conditions – Antibiotic prescribing. Health Service Executive. 2022. Available at: www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/2/gp/antibiotic-prescribing/conditions-and-treatments/urinary/uti-inpregnancy/uti-in-pregnancy.html

References on request

Theresa Lowry-Lehnen, RGN, PG Dip Coronary Care, RNP, BSc, MSc, PG Dip Ed (QTS), M Ed, PhD, Clinical Nurse Specialist, and Associate Lecturer, South East Technological University

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.