Local oestrogen therapy is the most effective treatment for genitourinary syndrome of menopause, which is a common and sometimes debilitating condition

With increasing longevity worldwide and especially in developed countries, women can now expect to live approximately 40 per cent of their lives after menopause. As such, there is a growing desire for older women to preserve their vitality, sexual function, and quality-of-life. The genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), previously known as vulvovaginal atrophy, atrophic vaginitis or urogenital atrophy describes signs and symptoms that occur in the vulva, vagina and lower urinary tract of menopausal women as a result of local oestrogen deficiency.

Concerns include: Genital symptoms (dryness, burning, and irritation); sexual symptoms (lack of lubrication, dyspareunia); and urinary symptoms (frequency, urgency, dysuria, urinary incontinence, and recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs)). Risk factors for GSM include: Cigarette smoking; alcoholism; ovarian failure, surgical; or premature menopause; lack of exercise; and absence of vaginal delivery.

Etiology

The incidence of GSM is difficult to determine as many women do not seek medical advice due to the stigma associated with discussion of sexual dysfunction or the acceptance that it is a consequence of natural aging. A large cohort study of Western population estimated GSM to occur in 45-63 per cent of post-menopausal women. Where abrupt menopause occurs in the context of surgical menopause, women experience more profound effects of sexual function and lower quality of life as a result. While the vasomotor symptoms of menopause generally improve over time, GSM is a chronic condition which, if left untreated, progresses over time leading to a significant impact on the quality-of-life of post-menopausal women.

Evaluation

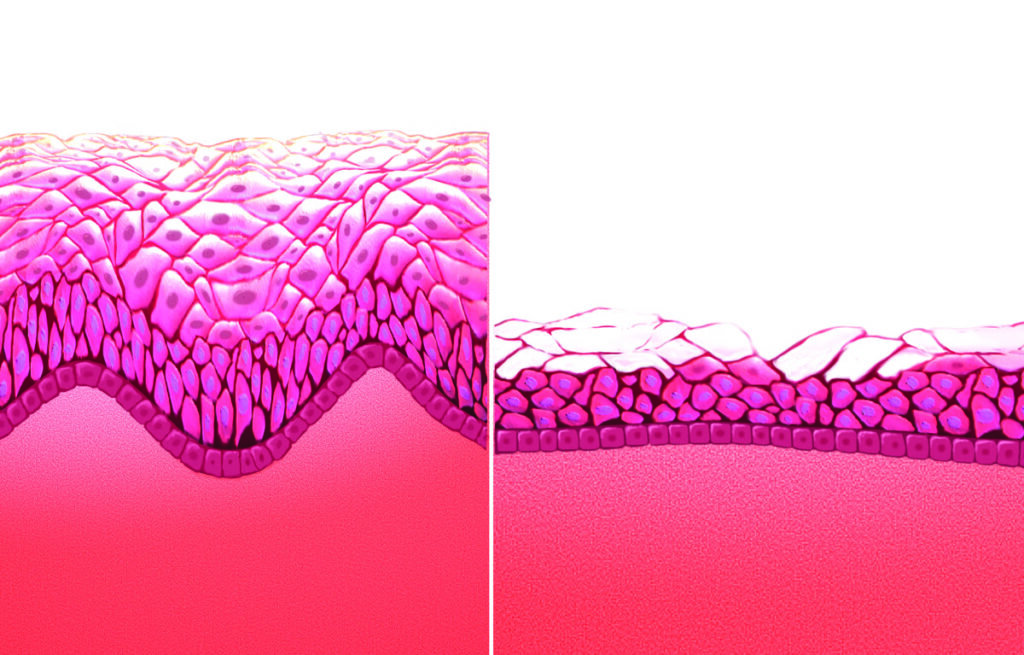

Women suspected of GSM require a thorough history and physical examination. Irritants resulting in discomfort in the genitourinary area should be screened for, including such things as lubricant, powder, soap, spermicide and panty liners. A history of bilateral oophorectomy, pelvic radiation, chemotherapy or anti-oestrogen medication can all increase the likelihood of GSM, particularly in pre-menopausal women. A woman with vaginal atrophy may experience contact bleeding with medical examination and a gentle examination should be performed. On examination vaginal atrophy is defined by pale and shiny vaginal epithelium and areas of erythema may also be present. There can be a thinning of the cervix, loss of labial fat pads, and a shortened, narrowed vagina.

Other features to assess include laceration, labial fusion, vaginal stenosis and friable skin. Cystoscopic findings consistent with hypoestrogenism include: Pallor and squamous metaplasia of the trigone; urethral shortening; pale urethral epithelium; urethral caruncle; intrinsic sphincter dysfunction; and reduced bladder compliance. One must rule out other differential diagnoses including: Bacterial vaginosis; trichomoniasis; candidiasis; contact irritants; foreign bodies; neoplasia; carcinoma in situ of external or internal female genitalia; endocrine disorders; and vulvar skin conditions including lichen sclerosis or lichen planus.

Vulvovaginal symptoms

GSM signs and symptoms are divided into those of the external genitalia and/or urological tract. Vaginal atrophy most often presents as vaginal dryness, but may also present as dyspareunia, vaginal itching, vaginal discharge and vaginal pain. The most common presenting complaint is superficial dyspareunia as a result of vaginal atrophy. Lack of lubrication may lead to abrasion and fissure formation during intercourse with resultant dyspareunia. In anticipation of this pain, vaginismus, spasm of the vaginal muscles, and hypertonicity of the pelvic floor may occur as a response to this anxiety.

The Clarifying Vaginal Atrophy’s Impact on Sex and Relationships (CLOSER) study found vaginal discomfort to be directly related to lack of intimacy (women, 58 per cent; men, 78 per cent) and lack of libido (women, 64 per cent; men, 52 per cent) between partners. Vaginal symptoms of menopause have a significant negative impact on sexual pleasure (59 per cent), sleep (24 per cent), and overall quality-of-life (23 per cent).

The vasoactive properties of oestrogen increases vaginal lubrication, which is caused by fluid transudation from blood vessels, endocervical glands and the Bartholin’s glands. Epithelial proliferation within the smooth muscle tissue layer (vaginal muscularis) occurs with oestrogen receptors activation. This causes rugae formation, which improves vaginal compliance by allowing distension, expansion and lubrication of the vagina with sexual arousal. Loss of oestrogen receptor activation can thus cause irritation and dyspareunia.

Urinary symptoms

Oestrogen receptors also exist in the pelvic floor musculature and endopelvic fascia. Reduction in oestrogen at the trigone of the bladder and in the urethral epithelium reduces the sensory threshold of the bladder which results in overactive bladder symptoms, and a reduction in the urethral closure pressure and Valsalva leak point pressure thereby increasing episodes of stress urinary incontinence. One study reported that 20 per cent of post-menopausal women experienced urge incontinence while approximately 50 per cent experienced stress urinary incontinence (Robinson et al, 2003).

After menopause, women also often suffer from recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs), defined as at least three acute UTI episodes within a year or two in six months (Hayden et al, 2012). It has been shown that vaginal oestrogen reduces the risk of rUTI; however, the same is not true of systemic oestrogen therapy. In contrast to the pre-menopausal state, Lactobacilli present within the vaginal microbiome of post-menopausal women produce less lactic acid, hydrogen peroxide and bactericidal proteins, and a resultant rise in vaginal pH. These factors impair the host’s immune response and may contribute to higher rates of UTI in the post-menopausal period. When Lactobacillus is restored in the vaginal microbiome following local oestrogen therapy, host defences recover within 12 weeks of use.

In its 2013 position statement, NAMS stated that progesterone is required to combat the risk of endometrial cancer in women using systemic HRT with an intact uterus

The vaginal microbiome directly interacts with the bladder microbiome and manipulation of the vaginal microbiome has been shown to decrease occurrence of lower urinary tract symptoms and disease by replenishing it with protective Lactobacillus species. High post void residuals (PVRs) are associated with rUTIs in the post-menopausal period and an association between the hypoestrogenic state and high post-void residual urine is well-established. The mechanism through which this occurs is through stasis of microbes within the bladder and impaired clearance, allowing bacterial colonisation and infection. Oestrogen in rabbit bladders has been shown to increase the volume of smooth muscle cells and bladder vascularisation, while increasing collagen formation, resulting in increased bladder contractility.

Oestrogen

There are three forms of oestrogen produced by the ovaries including oestradiol, estrone, and estriol. Estradiol is the most abundant oestrogen in pre-menopausal women, and estrone, a less potent form of oestrogen, becomes the predominant type after menopause. The female genital tract comprising the vaginal vestibule and lower fifth of vagina, and the lower urinary tract comprising the bladder, trigone, and urethra, share a common embryological origin, the urogenital sinus, and have common oestrogen receptor function. Although the number of oestrogen receptors reduce in number in the post-menopausal period, they do not disappear altogether. Hypoestrogenism results in a reduction in collagen and hyaluronic acid, elastin, epithelial thinning and reduction in blood flow to the female genital tissues. Restoration of these receptors, which decline with menopause, is possible with local oestrogen treatment.

The post-menopausal vagina is made up of columnar epithelium. Oestrogen converts the columnar epithelium of the vaginal tract into a layer of stratified squamous epithelium, which elevates the glycogen content. A healthy, oestrogenised vaginal flora is composed of both aerobic and an-aerobic, gram positive and gram negative bacteria. In an oestrogenised vagina, lactobacillus is the predominant bacterial genus and metabolises glucose into lactic acid and acetic acid, which acts as a protective mucous layer and lowers the vaginal pH to a range of 3.5-4.5. This acidic environment reduces urinary tract infections and vaginitis and protects against the growth of pathogenic bacteria and infection.

Systemic hormone replacement therapy (HRT) has been approved for osteoporosis prevention and treatment of vasomotor symptoms in menopausal women. However, systemic HRT is associated with a risk of venous thromboembolism, coronary heart disease, endometrial and breast cancer. Long-term systemic HRT is no longer recommended if considered solely for the treatment of vaginal atrophy. Both the International Menopause Society Writing Group, and the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) make recommendations for local oestrogen supplementation in the treatment of GSM and recurrent UTI, as this does not have side effects associated with systemic hormone replacement therapy. In contrast to systemic oestrogen for treatment of vasomotor symptoms and osteoporosis risk reduction, topical oestrogens do not improve such symptoms.

Local oestrogen therapy offers the most effective and fastest symptomatic relief of GSM symptoms, with up to 90 per cent reporting subjective symptom improvement. GSM is a chronic condition, which may require indefinite use of local oestrogen therapy, as long as symptoms persist. It has been shown that shortly after the start of treatment, once the vaginal epithelium has recovered from the atrophic state, systematic absorption of oestradiol is minimal. Because vaginal oestrogens fall into the general category of oestrogen therapies, package inserts on local vaginal oestrogen treatments carry the same warnings as systemic oestrogens, despite there being no systemic risks once the vaginal epithelium is no longer atrophic. There is no evidence of endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma development with local oestrogen treatment and currently annual surveillance of endometrial thickness is not advised.

Contraindications to the use of local oestrogen therapy include: Known or suspected cases of breast cancer; oestrogen-dependent cancers; undiagnosed vaginal bleeding; endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial cancer.

Local oestrogen therapy can be in the form of vaginal tablets, creams, or rings. The 2006 Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews showed that delivery methods are equally as effective in resolution of GSM symptoms. One must consider personal preference in deciding application mode. In the VIVA survey, vaginal discomfort was reported mainly by those using vaginal hormonal creams (13 per cent) and tablets (12 per cent) and to a lesser extent by women using hormonal rings (1 per cent). When commencing women on local oestrogen therapy, it is important to counsel them regarding possible side effects such as vaginal secretion, vaginal spotting, and genital pruritus.

The tablet form tends to have less associated discharge; however, in the presence of external signs of atrophy, such as a urethral caruncle, the use of a cream may be more appealing. Vaginal rings in contrast are low maintenance and last three months before a change is required; however, dexterity is required for insertion and removal. Pelvic organ prolapse may also result in ring expulsion or displacement and some patients may describe increased discharge resulting from a foreign body-type reaction.

There are currently two vaginal creams available: Premarin (Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc, part of Pfizer, Inc, New York, NY, USA) and Estrace (Warner Chilcott [US], LLC, Rockaway, NJ, USA). Premarin contains 0.625mg conjugated equine oestrogens (CEE) per gram of cream.

The recommended dosage is 0.5-2.0g once daily for 21 days, followed by 0.5g twice weekly. In a randomised, placebo-controlled study comparing low-dose CEE to placebo there were no cases of endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma development after one year of treatment. Alternatively, estrace contains 0.1mg estradiol per gram of cream and it is recommended that 2-4g is used daily for one-to-two weeks, followed by a gradual reduction to half the initial dose over one-to-two weeks, and then 1g one-to-three times weekly for maintenance.

The Estring vaginal ring (Pharmacia and Upjohn Company, Division of Pfizer, Inc, New York, NY, USA) contains a 2mg estradiol reservoir. The ring releases approximately 7.5µg per day for 90 days. In an open-label study in women using Estring for one year, there were no cases of endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma development. The Vagifem vaginal tablet (Novo Nordisk A/S, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) contains 10µg estradiol. This ultra-low-dose vaginal tablet was introduced in 2010 to replace the previously available 25µg tablet. This ultra-low-dose provides symptomatic relief without systematic exposure. The recommended dose is 10µg daily for two weeks, then twice weekly for maintenance. There was no incidence of increased endometrial thickness or endometrial hyperplasia following a years’ treatment with 10µg of vaginal estradiol.

In its 2013 position statement, NAMS stated that progesterone is required to combat the risk of endometrial cancer in women using systemic HRT with an intact uterus. Progesterone, however, is “generally not indicated when low-dose vaginal oestrogen is administered”, which applies to the low dose vaginal ring and tablet. Vaginal creams deliver higher doses of oestrogen and there are currently no recommendations regarding concurrent progesterone use with vaginal cream application. In women with significant atrophy, vaginal creams may be used as the initial treatment and then changed to a lower dose delivery system once vaginal atrophy has improved.

With regards to women with a history of oestrogen-dependent breast cancer with GMS, local oestrogen therapy should be reserved for those who do not respond to non-hormonal treatments. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists committee opinion statement in 2016 states that if the decision is made to proceed with local oestrogen, this decision should be made in conjunction with the woman’s oncologist, however, data does not show an increased risk of cancer recurrence in women undergoing active breast cancer treatment or those with a personal history of breast cancer. There is a paucity of evidence regarding local oestrogen therapy in women with a personal history of endometrial cancer and so treatment commencement should also be discussed in coordination with their oncologist. Cervical, vaginal, and ovarian cancers are not hormone dependent and accordingly these should not prohibit the use of local oestrogen.

Conclusion

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause is a common, sometimes debilitating consequence of reduced oestrogen levels associated with menopause. Local oestrogen therapy is the most effective treatment and clinical response is rapidly seen. When over the counter treatments do not relieve symptoms, NAMS recommends local oestrogen therapy. A number of formulations exist, including tablets, creams and rings, and the physician and patient should work together to find the optimal management option. Due to the chronicity of GSM symptoms, treatment should continue as long as symptoms persist, and may in some cases require indefinite application. Long-term studies (up to one year) have shown no evidence of endometrial hyperplasia or cancer and this information should be used to reassure women when counselling them on local oestrogen therapy for treatment of GSM.

References on request

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.