Infectious mononucleosis should be suspected in patients who present clinically with the classic triad of

fever, pharyngitis, and cervical lymphadenopathy

Infectious mononucleosis, commonly known as glandular fever, characterised by fatigue, fever, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy is an infection usually caused by the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), (human herpesvirus 4) a member of the herpes virus family. It can affect people of any age, but is most common in young adults and teenagers aged 15-to-24 years. The infection is primarily spread through saliva, by kissing or exposure to coughs and sneezes and objects, such as eating and drinking utensils and toothbrushes.

Following exposure, EBV infects epithelial cells of the oropharynx and salivary glands. B lymphocytes may become infected through exposure to these cells or may be directly infected in the tonsillar crypts. B-cell infection allows viral entry into the bloodstream, which systemically spreads the infection.

The host immune response involves cytotoxic T-cells reacting against the infected B lymphocytes, resulting in enlarged, atypical lymphocytes.8 Infectious mononucleosis can also rarely be spread through other bodily fluids such as blood or semen. EBV can remain in saliva for up to 18 months post infection, and a few individuals may continue to have the virus present in their saliva intermittently for years. There is no vaccine for EBV, however, most individuals develop immunity after the initial infection.1,4,6

Infectious mononucleosis accounts for approximately 1 per cent of all patients who present with a sore throat. In those aged 16-to-20 years, however, it is the cause of about 8 per cent of throat infections. EBV causes approximately 90 per cent of cases of infectious mononucleosis, with the remainder due largely to cytomegalovirus, human herpesvirus 6, toxoplasmosis, HIV, and adenovirus. Because their management is much the same, it is not always necessary to distinguish between EBV mononucleosis and cytomegalovirus infection.

EBV causes approximately 90 per cent of cases of infectious mononucleosis, with the remainder due largely to cytomegalovirus, human herpesvirus 6, toxoplasmosis, HIV, and adenovirus

However, in pregnant women, differentiation of mononucleosis from toxoplasmosis is important, since it is associated with significant consequences for the foetus. After an incubation period of four-to-eight weeks, EBV infection of adolescents or adults results in infectious mononucleosis in up to 70 per cent of cases. Most symptoms tend to resolve in two-to-four weeks, although approximately 20 per cent of patients continue to complain of a sore throat after one month.3,4,8

Before puberty, the illness typically produces symptoms similar to those of common throat infections. In adolescence and young adulthood, the disease presents with a characteristic triad of fever, sore throat and lymphadenopathy. Other symptom include fatigue, headaches, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pains. The most prominent sign is pharyngitis accompanied by enlarged tonsils with exudate similar to strep throat. In approximately 50 per cent of cases petechiae can be seen on the roof of the mouth.

Spleen enlargement is common in the second and third weeks, although this may not be apparent on physical examination. Rarely, in approximately 1 per cent of cases, the spleen may rupture. There may also be some enlargement of the liver.2,3 When adults over the age of 40 develop the illness, they display less characteristic symptoms and are more likely to develop prolonged fever, fatigue, malaise, and body pains with liver enlargement and jaundice.3,4

Diagnosis

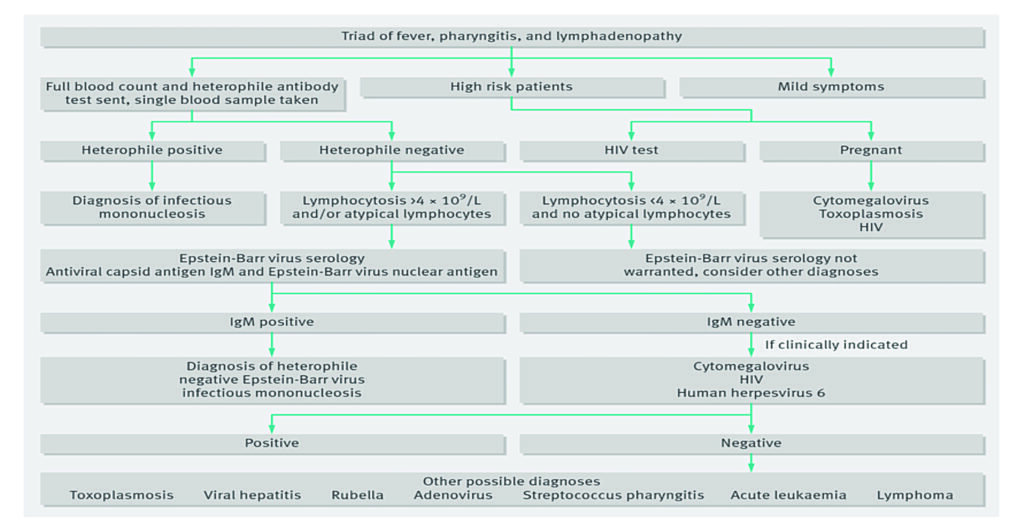

Infectious mononucleosis should be suspected in patients who present clinically with the classic triad of fever, pharyngitis, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Lymphadenopathy may be prominent in both the anterior and posterior triangles of the neck, which distinguishes infectious mononucleosis from bacterial tonsillitis where the lymphadenopathy is usually limited to the upper anterior cervical chain. Other common physical signs include palatal petechiae, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and jaundice. Diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis is primarily based on symptoms, but should be confirmed by the heterophile antibody monospot test. Sensitivity is 85 per cent and specificity is 100 per cent. The heterophile antibody monospot test results may be negative early in the course of EBV infectious mononucleosis.

Positivity increases during the first six weeks of the illness. Patients who remain heterophile-negative after six weeks with a mononucleosis illness are considered to have heterophile-negative infectious mononucleosis and should be tested for EBV-specific antibodies. Patients who are heterophile-positive, but specific antibody-negative, should be considered for testing for possible causes of false positive heterophile antibodies. A real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test identifying infectious mononucleosis DNA may be useful in cases of diagnostic doubt or where rapid diagnosis is helpful, such as in patients with a high risk of splenic rupture.9

White blood cell count and differential can be useful in establishing a diagnosis. A typical finding is increased blood lymphocytes. Liver function tests (LFTs) are also abnormal in more than 90 per cent of patients with infectious mononucleosis. Serum transaminase and alkaline phosphatase levels are usually moderately elevated.

The serum bilirubin may be increased in approximately 40 per cent of patients, but jaundice typically only occurs in approximately 5 per cent of infectious mononucleosis cases.7,8 ESR is elevated in most patients with infectious mononucleosis, but is not elevated with group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Abdominal ultrasound may be required to assess for splenomegaly and other investigations may be required to differentiate from other possible diagnoses, for example, lumbar puncture for meningism.9

CAEBV

Chronic active Epstein–Barr virus (CAEBV) infection is a rare condition characterised by severe, chronic, or recurrent infectious mononucleosis-like symptoms after a well-documented primary infection with EBV in a previously healthy person. The disease is progressive with markedly elevated levels of EBV DNA in the blood and infiltration of organs by EBV-positive lymphocytes. Patients often present with fever, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, EBV hepatitis, or pancytopaenia. Over time, these patients develop progressive immunodeficiency and, if untreated, develop infections, haemophagocytosis, multi-organ failure, and EBV-positive lymphomas. The only proven effective treatment for chronic active EBV is hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.2,3

Complications

Infectious mononucleosis usually resolves over a period of weeks, but occasionally can be exacerbated by complications. While uncommon, complications can be serious when they occur. Complications include secondary infection of the brain or nervous system, breathing difficulties as a result of inflamed tonsils and ruptured spleen. Airway obstruction may develop in patients with severe inflammation and swelling of the tonsils and adenoids. This complication may occur in one of every 100-to-1,000 cases and most often occurs in younger patients with infectious mononucleosis.4,8 Neurological disorders may occur in 1-to-5 per cent of patients.

These include encephalitis, meningoencephalitis, seizures, optic neuritis, sudden sensorineural hearing loss, idiopathic facial palsy, and Guillain-Barré syndrome.2,3 Haematological complications are more common, particularly haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopaenia and rarely, aplastic anaemia, pancytopaenia, and agranulocytosis. Other rare acute complications include myocarditis, pericarditis, pancreatitis, interstitial pneumonia, rhabdomyolysis, and psychological complications.3 There is evidence that a history of infectious mononucleosis significantly increases (doubles) the risk of multiple sclerosis.3 Severe abdominal pain is uncommon in patients with infectious mononucleosis, and should prompt immediate reaction to the possibility of splenic rupture.8

Treatment

Infectious mononucleosis can be treated in most cases with rest, hydration, analgesia, and antipyretics. Paracetamol and NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, may be used to reduce fever and pain. Antibiotics are not effective in treating infectious mononucleosis, because they have no effect on viral infection. Antibiotics may be prescribed if a secondary bacterial infection of the throat occurs, however, ampicillin and amoxicillin are not recommended during acute EBV infection, as a diffuse itchy maculopapular rash may develop.3,4,5

Most symptoms tend to resolve in two-to-four weeks, although approximately 20 per cent of patients continue to complain of a sore throat after one month

Although antivirals are not usually recommended for people with simple infectious mononucleosis, they may be useful in the management of severe EBV manifestations, such as EBV meningitis, peripheral neuritis, hepatitis, or haematologic complications. Antiviral treatment with acyclovir has been shown to significantly decrease the rate of oropharyngeal EBV shedding. There is insufficient evidence to recommend steroid treatment for symptom control in infectious mononucleosis, however, short courses of corticosteroids are beneficial for haemolytic anaemia, central nervous system involvement or extreme tonsillar enlargement.9

The need for rest and return to usual activities after the acute phase of the infection should be based on the person’s general energy levels. However, to decrease the risk of splenic rupture, avoidance of contact sports and heavy physical activity is advised for the first three-to-four weeks or until enlargement of the spleen has resolved. Alcohol should be avoided for the duration of the illness.3,4,5

Resolution of the acute illness is usually followed by a lifelong latent infection. Once the acute symptoms of an initial infection resolve, they usually do not reoccur, however, the virus remains dormant in B lymphocytes in the body and the person is a carrier for the rest of their life. Independent infections of mononucleosis may be contracted, regardless of whether the person is already carrying the dormant virus. Occasionally, the virus can reactivate, during which time the person is again infectious, but usually without any symptoms of illness. However, in susceptible hosts the virus can reactivate causing vague physical symptoms, and during this phase the virus can spread to others.

References

- MSD (2019). Infectious Mononucleosis. MSD Manual Professional Version. US. Available at www.msdmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/herpesviruses/infectious-mononucleosis

- Balfour H, Dunmire S, Hogquist K. (2015). Infectious mononucleosis. Clinical Translation Immunology. 4(2), Feb. doi: 10.1038/cti.2015.1 PMCID: PMC4346501

- Lennon P, Crotty M, Fenton J. Infectious Mononucleosis. BMJ 2015. Education Clinical Review. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1825. Available at: www.bmj.com/bmj/section-pdf/895012?path=/bmj/350/8005/Clinical_Review.full.pdf

- HSE (2018). Glandular Fever. Health Service Executive. Available at: www.hse.ie/eng/health/az/g/glandular-fever/treating-glandular-fever.html

- Bennett J, Dolin R, Blaser M. (2014). Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Elsevier Health Sciences. p.1760. ISBN 9781455748013

- Rezk SA, Zhao X, Weiss L. (2018). Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated lymphoid proliferations, a 2018 update. Human Pathology. 79: 18–41. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2018.05.020. PMID 29885408

- BMJ (2018). Infectious Mononucleosis. BMJ Best Practice. Available at: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/123?gclid=Cj0KCQjwy97qBRDoARIsAITONTK-4evuG9PmZxU8NL5pHlILFWFGk_Oieeo4wg6wLUY7A7weEA0Eup4aAvtyEALw_wcB

- Medscape (2019). Infectious Mononucleosis (IM) in Emergency Medicine. Available at: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/784513-overview

- Knott L. (2016). Infectious Mononucleosis. Patient Information. Available at: https://patient.info/doctor/infectious-mononucleosis

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.