Mastitis is a common complication during breastfeeding, however, many breastfeeding women do not get the information or support they need to avoid or manage it

Lactational mastitis (LM) refers to inflammation of the breast that may or may not be accompanied by infection during breastfeeding. Lactational is the most commonly reported form of mastitis, but it can occur outside of breastfeeding in both men and women, which will require further and urgent investigation. LM is usually mild and easily managed at home by patients through a variety of simple techniques, support, reassurance, and adequate education. In a small proportion of women, LM can become more serious, and in severe cases, requires hospitalisation. A lack of understanding and inadequate knowledge about prevention and management of the disorder is associated with the development of severe complications and presentations.1,2,3

Ireland has a high hospital admission rate for LM despite its notably low breastfeeding rates, and research suggests that these low rates of breastfeeding have contributed to low levels of expertise in the management of LM, and subsequently, higher rates of complications.2 Similarly, data from Glasgow has found that a small number of breastfeeding women continue to receive inappropriate guidance from their healthcare providers that could lead to complications, hospitalisation, and unnecessary cessation of breastfeeding.3 The GP and general practice nurse (GPN) are a vital link in the chain of breastfeeding support for many mothers, and in some cases, the primary one. An understanding of the condition, alongside education, support, and evidence-based interventions, are vital components of LM prevention and management, as well as knowledge of and collaboration with breastfeeding support organisations.

Causes and aetiology of non-infectious and infectious LM

The incidence of mastitis ranges globally from 3-to-20 per cent, with the two-to-three weeks after birth being the most common timeframe for development.4 There is no consensus on the exact cause of LM in the literature. There appears to be a continuum from engorgement, to non-infective LM, to infective LM, to breast abscess formation.4 Engorgement or milk stasis, which may be linked to a decrease in the number of breast feeds given, often occurs postnatally between day three and 10, whereby one or both breasts can become overfull, tight, shiny, warm, hard, and painful.4 This period can also advance to LM and its associated complications if not managed correctly. Obstructed or sluggish milk ducts and/or an excess milk supply that may block ducts if stagnant are also associated with LM development throughout the breastfeeding journey. A previous history of LM or breast trauma also increases the risk of development.4 Onset is usually gradual and unilateral for both non-infectious and infectious presentations.4,5

Non-infectious LM often begins with poor milk drainage and flow due to suboptimal removal of milk, sudden changes in the baby’s feeding pattern, trauma, pressure from holding the breast incorrectly, or pressure from restrictive clothing and bras.4,5,6 These issues lead to an obstruction in the milk ducts and engorgement of the breast. Milk may then leak into breast tissue, exacerbating the inflammatory response, and in some instances, contributing to the development of infection.

Patients should always be encouraged to continue to breastfeed, pump, or hand express and advised that avoiding feeding from the affected breast will lead to further milk stasis and worsening symptoms

Why infectious LM develops in some cases and not others is unclear, although there is evidence that certain bacteria, in particular Staphylococcus aureus, are more common in women with LM than those that do not develop the condition.4,5,6,7 Theories behind the aetiology of infectious LM include:4,5,7

- A bacterial infiltration through cracked nipples from the woman’s skin or infant’s mouth;

- Pathogenic bacteria present in breastmilk;

- A dysbiotic process resulting in overgrowth of some cultures and the extinction of others;

- Virulence factors;

- Production of biofilm;

- Antimicrobial resistance;

- Interaction with the host immune system.

Signs and symptoms

Early signs of LM include an erythematous, oedematous area on the breast that is usually tender or painful to touch and may present in a wedge-shaped formation. A breast lump or tissue thickening may or may not be palpable. The nipple may be pushed flat by oedema or engorgement and feel firm to touch. The patient might also experience a pain or burning sensation that is constant, or only during feeding. These symptoms do not necessarily indicate the presence of infection. Some women may feel generally unwell, but this is usually symptomatic of infectious LM, which may also be accompanied by pyrexia, chills, flu-like symptoms, and hot, painful areas on the breast.4,6,7 In more serious cases of acute infective LM, patients may also present with nipple inversion, thick nipple discharge, breast abscess, or draining fistulas.7 A breast abscess is a closed-in, localised collection of pus that lacks an outlet. Abscesses are more common in primiparous women, women aged over 30 years, and mothers who give birth post-term.4 Surgical intervention is frequently required to treat this complication. These more severe presentations of complicated infective LM will require immediate review by the GP and potentially hospitalisation for ultrasound, intravenous antibiotics, and further investigation and/or treatment.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of non-infectious and infectious LM is based on breast examination, clinical history, and presenting signs and symptoms. History-taking should include a breastfeeding and obstetric history, symptom history, mother’s own history, and baby’s history.4 Consent, hand hygiene, and reassurance will be required for the breast examination. Samples of breast milk may be sent for culture if infection is suspected and any indication of complicated or infectious LM should be reviewed by the GP.4,7 Any breast lump, swelling, or abnormality that does not get significantly smaller within a week of treatment should also be examined by the GP and may be indicative of more serious disease or infection.7

Management of non-infectious LM

Women themselves have emphasised the importance of continuity, individualised care, and consistent information as vital elements of LM management.1 Clinically, the continuation of breastfeeding is the core component of any approach. Therefore, the highest standards of care will encompass all of these elements. It is important to be aware that one of the most common and adverse complications of LM is early termination of breastfeeding.7 Patients should always be encouraged to continue to breastfeed, pump, or hand express and advised that avoiding feeding from the affected breast will lead to further milk stasis and worsening symptoms.1,3,4,5,6,7,8 Ultimately, breastfeeding is the preferred way to relieve blockages and symptoms of LM, but the process may be difficult and painful for patients. Therefore, many will need added reassurance, education, and support to continue feeding. Breastmilk may not release if the patient is in pain, and analgesia may also be required. Paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), like ibuprofen, can be used for pain control in LM while breastfeeding.7,8

Evidence also exists to support the application of cold cabbage leaves in the reduction of pain and alleviation of symptoms of engorgement.9 One tablespoon per day of oral granular lecithin has also been reported to relieve clogged ducts and help prevent LM recurrence.4,10 Therapeutic ultrasound, which is administered by a trained lactation consultant or physiotherapist, is sometimes used to release obstruction and improve milk flow, and may be required daily for several days if symptoms persist.6 It is important that patients are aware that the affected breast may produce less milk temporarily after an episode of LM and that regular, uninterrupted breastfeeding and skin contact with the baby will encourage milk production and flow to normalise. Educating patients about recognising the signs and symptoms of infectious LM, such as pyrexia and chills, will help to reduce the risks of serious infection development and promote early intervention.

Management of infectious LM

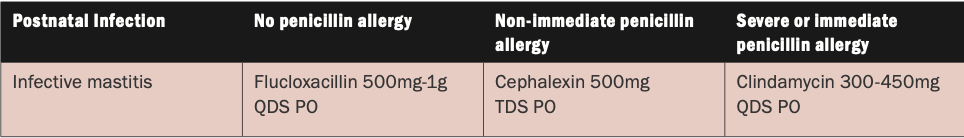

The management techniques discussed for non-infectious LM can be implemented for infectious presentations too. In particular, continuation of breastfeeding remains the cornerstone of management.1,3,4,5,6,7,8 Fully emptying the breasts of excess milk regularly has been shown to decrease the duration of symptoms in patients treated with and without antibiotics.4 Hand hygiene should also be recommended for all the family and the importance of skincare and hygiene of the breasts should be reinforced to the patient. Any equipment, such as breast pumps, should be sanitised to minimise further microbial invasion. In the absence of breast abscess or serious infection requiring intravenous therapy and/or surgical input, antibiotic therapy is usually commenced orally, as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: HSE Medication Guidelines for Obstetrics and Gynaecology: Antimicrobial Prescribing Guidelines11

Practical advice and education

Providing reassurance, education, and advice on how to manage both forms of LM is key to optimal recovery and the continuation of breastfeeding. Simple, natural interventions that may make breastfeeding easier during episodes of non-infectious and infectious LM include:4,6,7

Gentle breast massage before and during feeding, primarily focused on the affected area and surrounding tissue to help unblock ducts.

Using a warm, moist compress on the affected breast for two-to-three minutes (or up to 20 minutes if required) before feeding may also improve flow.

Cold packs applied to the breast after emptying can help reduce oedema and pain.

While in the shower, patients can lather and massage the breast with a steady, but gentle pressure behind the affected area, pressing toward the nipple.

Starting a breastfeeding session on the affected breast is advisable. If the milk does not release or feeding becomes too uncomfortable, recommend that the patient switch to the unaffected breast for a period, then try again and continue to alternate as tolerated.

Positioning the baby with its chin facing the blockage of the affected breast may also promote improved drainage.

Advise patients to try gentle hand expressing or using a breast pump if feeding is too painful or not possible.

Reinforce the importance of staying adequately hydrated and rested.

Prevention of LM

Prevention of LM can be enhanced when pregnant and breastfeeding mothers receive adequate education about how to recognise and minimise their risks of developing the condition. The promotion of exclusive breastfeeding will in itself promote prevention. A variety of potential risk factors for LM development have been identified by experts and include:4,5,6,7,8

- Poor positioning and/or attachment of the infant to the breast;

- Damaged skin integrity of the nipple or breast;

- Use of bottles or pacifiers;

- Too rapid weaning, infrequent feeds, or missing feeds;

- Uneven breast drainage, incorrect attachment during feeding, and problems with baby sucking;

- Distractions that prevent or delay the baby or mother breastfeeding;

- Illness in mother or baby;

- Sustained pressure on the breast from sources that include ill-fitting bras, breast shells worn for too long in a bra with too small cups, slings with straps that press into the breast and stomach;

- Stress and fatigue;

- Nipple piercings and scar tissue could interfere with milk transfer and contribute to blocked ducts and mastitis;

Use of antifungal and other nipple creams.

Conversations about these modifiable risk factors will be paramount in preventing LM development. Ideally, education should start in the antenatal stages and continue postnatally throughout the breastfeeding journey. Support from family members and other healthcare providers is also an important element of both prevention and management. The optimal approach will be a multidisciplinary one.

Conclusion

There are many resources available to help GPs and breastfeeding mothers to prevent, recognise, and manage LM effectively. Knowing what services are available from statutory and voluntary organisations will help guide care and decision-making. Specialist supports are available in the community, including public health nurses (PHNs) and International Board-Certified Lactation Consultants (IBCLCs). Becoming familiar with the breastfeeding and antenatal classes available in local maternity units, as well as the booking systems for them, is also an important element of patient education. Voluntary groups, such as La Leche League, Cuidiu, Friends of Breastfeeding, and The Breastfeeding Supporter can also provide valuable resources and support.4

The nationwide database of hospital, public health and voluntary breastfeeding supports is available at: www.breastfeeding.ie/Support-search/.

To find an IBCLC and a host of valuable resources and information, visit the Association of Lactation Consultants in Ireland (ALCI) at: www.alcireland.ie/find-a-consultant/.

Information about support groups for breastfeeding in the local area is available from the HSE at: www2.hse.ie/services/breastfeeding-support-search/.

References

1.Tøkje IK, Kirkeli SL, Løbø L, Dahl B. Women’s experiences of treatment for mastitis: A qualitative study. Eur J Midwifery. 2021 Jun 29;5:23

2. Cooney F, Petty-Saphon N. The burden of severe lactational mastitis in Ireland from 2006 to 2015. Ir Med J. 2019 Jan 15;112(1):855

3. Scott JA, Robertson M, Fitzpatrick J, Knight C, Mulholland S. Occurrence of lactational mastitis and medical management: A prospective cohort study in Glasgow. Int Breastfeed Journal. 2008 3,21

4. Health Service Executive. Mastitis: Factsheet for healthcare professionals. Available at: www.hse.ie/file-library/mastitis-factsheet-for-healthcare-professionals.pdf

5. Wilson E, Woodd SL, Benova L. Incidence of and risk factors for lactational mastitis: A systematic review. Journal of Human Lactation. 2020;36(4):673-686

6. Health Service Executive. Mastitis while breastfeeding. 2022. Available at: www2.hse.ie/conditions/mastitis/

7. Blackmon MM, Nguyen H, Mukherji P. Acute mastitis. [Updated 2022 Jul 18]. In:StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/books/NBK557782/

8. National Health Service Northern Ireland. Mastitis. 2022. Available at: www.nidirect.gov.uk/conditions/mastitis

9. Boi B, Koh S, Gail D. The effectiveness of cabbage leaf application (treatment) on pain and hardness in breast engorgement and its effect on the duration of breastfeeding. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2012;10(20):1185-1213

10. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) Bethesda (MD). National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Lecithin. 2006 [Updated 2022 Sep 19]. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501772/

11. Health Service Executive Clinical Programme in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Medication guidelines for obstetrics and gynaecology – Antimicrobial prescribing guidelines. 2017. Available at: www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/clinical-strategy-and-programmes/antimicrobial-safety-in-pregnancy-and-lactation.pdf

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.