Vaginal health is integral to a woman’s overall wellbeing, impacting both physical and emotional health. It is influenced by various factors, including hormonal changes and lifestyle choices. The vaginal microbiome, which plays a vital role in maintaining vaginal health, is a dynamic ecosystem predominantly made up of Lactobacillus species. These bacteria produce lactic acid, which helps maintain the vaginal pH between 3.8 and 4.5, an acidic environment essential for preventing the overgrowth of harmful bacteria and pathogens.

Other microbiota, including anaerobes, are present in smaller amounts. Under certain conditions, such as changes in hormone levels or antibiotic use, these bacteria can proliferate and lead to infections.1,2,3,4

Factors that affect the balance of the vaginal microbiome include hormonal changes, sexual activity, antibiotic use, douching, and diet. When this balance is disrupted, common vaginal health conditions like yeast infections and bacterial vaginosis (BV) can occur.1,2,3,5

Vulvovaginal candidiasis

Vulvovaginal candidiasis is caused by the overgrowth of Candida albicans, which normally exists in small amounts within the vagina. However, when the balance of the vaginal microbiome is disturbed, candida can multiply, leading to an infection.5

Symptoms

Symptoms of vaginal yeast infections include itching and irritation of the vulva, thick white creamy discharge, redness and swelling, and burning during urination or intercourse. Symptoms are often prominent just before a woman’s menstrual period. Common causes include antibiotic use, which can kill beneficial Lactobacillus bacteria, and hormonal changes, such as those occurring during pregnancy or due to oral contraceptives. People with poorly controlled diabetes or weakened immune systems are also at higher risk for yeast infections.5,6,7,8

Diagnosis

Diagnosing a vaginal yeast infection begins with a review of symptoms and a physical examination. The diagnosis can be made clinically based on the description and appearance of the vulva, and the presence of vaginal discharge. A high vaginal swab (HVS) is not required to start empiric treatment on first presentation. A HVS can be useful in women experiencing recurrent symptoms or failing to respond to treatment to confirm the presence of candida, the type of candida species, and sensitivities where resistance to azoles is suspected. Azole resistance is not common.6 In cases of recurrent infections or when the infection does not respond to standard treatments, a culture may be performed to identify the specific species of yeast, as some non-albicans species can be more resistant to common antifungal treatments.7

Differential diagnoses include allergic reactions, atopic dermatitis, lichen sclerosis, and psoriasis, among others.6,7 Sexually transmitted causes of vaginal discharge should be considered based on sexual history and testing for chlamydia, gonorrhoea, and trichomoniasis carried out if required.6

Treatment and management

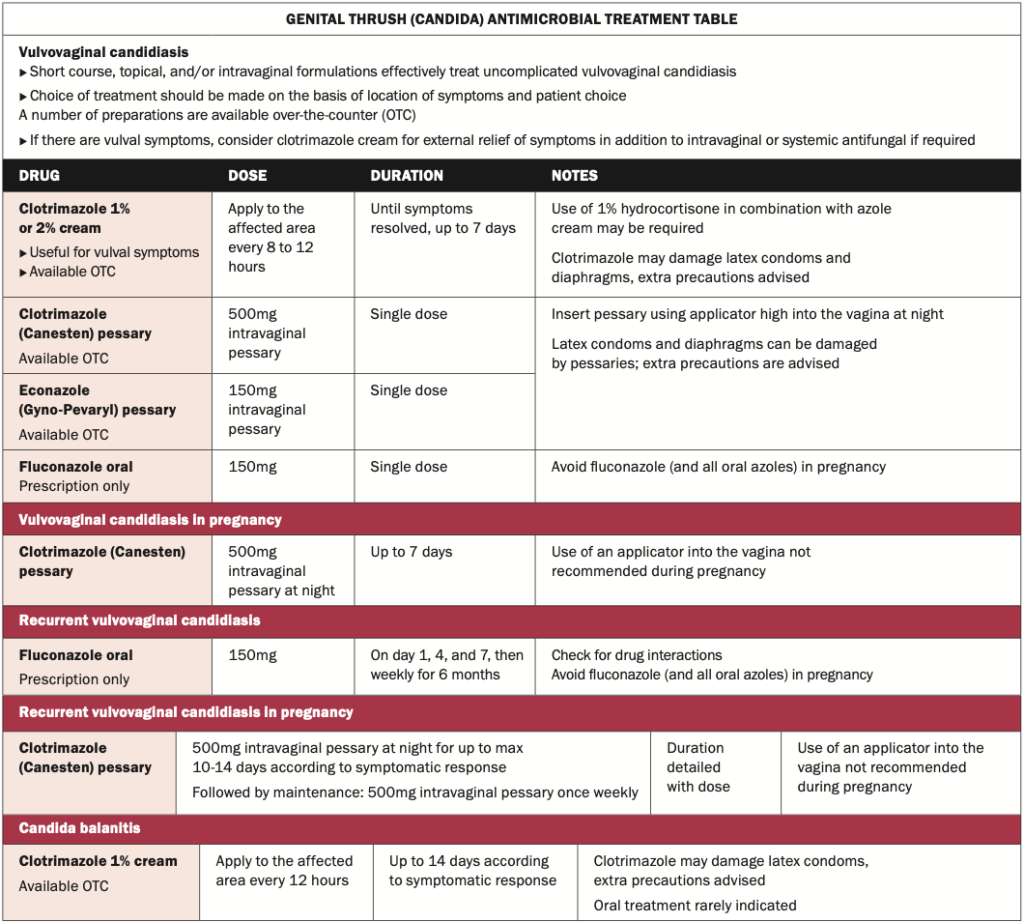

Yeast infections are commonly treated with antifungal medications, which are available in both over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription forms. These medications come in a variety of formulations, including creams, ointments, suppositories, and oral tablets. OTC antifungal medications are a convenient option for many women experiencing a vaginal yeast infection. These treatments typically include active ingredients such as clotrimazole, miconazole, or tioconazole. They are available in various treatment durations, ranging from one-to-seven-day regimens. Although effective, these treatments may cause local irritation or burning for some patients.5,6,7

For more severe or recurrent yeast infections, prescription treatments may be necessary.6,7,8 Fluconazole, an oral antifungal medication, is commonly prescribed as a single dose, although more doses may be required for persistent infections. For women with recurrent infections, a longer course of antifungal therapy may be recommended, followed by maintenance therapy to prevent recurrence. In cases where non-albicans species of candida are involved, treatments may differ, as these species can be resistant to standard antifungals. Clinicians may prescribe alternative medications. Pregnant women should not be given oral antifungals. In these patients, a seven-day course of intravaginal treatment is recommended. Fluconazole is considered safe in breastfeeding women.5,6,7,8

Recurrent vaginal yeast infections can be particularly challenging for women, both physically and emotionally. In these cases, it is important to investigate underlying causes such as poorly controlled diabetes, immune system disorders, or hormonal imbalances. Long-term antifungal treatments, either oral or topical, may be recommended to manage recurrent infections.5,6,8 The definition of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis is accepted as four or more episodes per year, two of which are confirmed on microscopy or culture when symptomatic. Careful consideration should be given to alternative diagnoses such as lichen sclerosis, eczema, or other dermatological conditions. Referral to genito-urinary medicine or dermatology may be warranted.6

Prevention of vaginal yeast infections involves both lifestyle modifications and awareness of factors that can disrupt the vaginal environment. Simple measures include avoiding the use of harsh soaps, douching, and scented feminine products, all of which can disturb the natural balance of bacteria and yeast in the vagina. Wearing breathable cotton underwear and avoiding tight clothing can also help reduce moisture build-up, which can encourage yeast growth.5,7

For women who experience frequent yeast infections related to antibiotic use, probiotics, particularly those containing Lactobacillus species, may help restore the natural vaginal flora. While evidence supporting the use of probiotics is still evolving, some studies suggest they can play a role in maintaining a healthy vaginal environment.1,2,9

As research into the vaginal microbiome advances, more targeted therapies for yeast infections may become available. Scientists are exploring the use of microbiome-modulating treatments, including probiotics and prebiotics. Personalised medicine is becoming an area of interest in the treatment of recurrent yeast infections. Identifying specific risk factors, such as genetic predispositions or lifestyle influences, could allow for more individualised treatment plans aimed at reducing infection rates.1,2,9

Bacterial vaginosis

BV is a common vaginal infection, particularly in women of reproductive age. It occurs when the balance of vaginal bacteria is disrupted, allowing anaerobic bacteria like Gardnerella vaginalis to overgrow. Unlike yeast infections, which are caused by fungi, BV is the result of an imbalance in the bacterial composition of the vaginal microbiome.10,11

Symptoms

Symptoms of BV include a thin grey or white discharge with a strong fishy odour, especially after intercourse. Itching or irritation is less common, but some women may experience burning during urination. BV is not classified as a sexually transmitted infection, but it is more likely to occur in individuals with new or multiple sexual partners. Other risk factors include douching, which disrupts the natural vaginal flora, and smoking, which can impair immune function and affect the vaginal environment.10,12

While BV can be asymptomatic or cause only mild discomfort, it can have significant health implications if left untreated. BV increases the risk of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, herpes, chlamydia, and gonorrhoea.

In pregnancy, BV has been linked to preterm birth, low birth weight, and miscarriage. The condition has also been associated with an increased risk of developing pelvic inflammatory disease, a serious infection of the reproductive organs that can lead to infertility if left untreated. Additionally, women with BV are at a higher risk of infection following gynaecological surgeries, such as hysterectomy or abortion.10,11,12

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of BV can be made clinically based on the description and appearance of the discharge. The normal pH of the vagina is increased from normal <4.5 to above 4.5 and up to 6.0, reflecting the replacement of normal Lactobacilli with anaerobic organisms. Treatment can be started without doing a HVS.12

A HVS is indicated when assessing abnormal vaginal discharge, but is not part of an asymptomatic sexually transmitted infection screen. Gram staining from a HVS in people with BV will demonstrate changes in the normal vaginal flora. A diagnosis of BV should not be made solely on demonstration of changes in the vaginal flora consistent with BV and/or the presence of organisms associated with BV (eg, Gardnerella species) on a HVS.12

It is important to establish the risk of a sexually transmitted cause of vaginal discharge based on sexual history. There is no benefit in treating male partners. Consideration should be given to partners of women who have sex with women.12

For women experiencing repeated episodes of BV, the diagnosis should be reconsidered, with further examination as appropriate. Adherence to treatment should be established, and repeated exposure to contributing factors such as unprotected sexual intercourse and vaginal douching should be assessed.10,11,12

Treatment and management

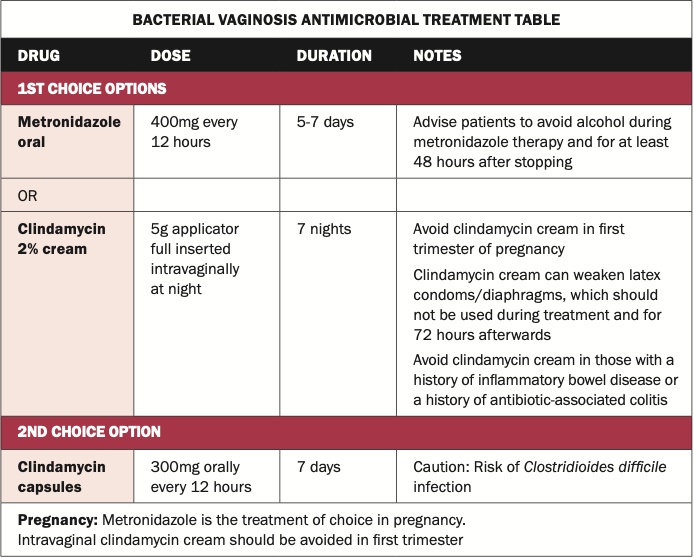

Treatment for BV typically involves antibiotics, such as metronidazole or clindamycin. It is important for individuals to complete the full course of antibiotics to reduce the risk of recurrence.9,10 Women may benefit from using lactic acid vaginal gels to facilitate restoration of the normal vaginal flora. Preparations are available OTC in pharmacies.10,12

The most commonly prescribed treatments include:9,10,12

- Metronidazole is the first-line treatment for BV. The oral form is usually taken for five-to-seven days. Side-effects of oral metronidazole can include nausea, a metallic taste in the mouth, and a risk of interactions with alcohol.

- Clindamycin is an alternative for women who cannot tolerate metronidazole. The cream form may weaken latex condoms, so alternative contraception is advised during treatment.

Recurrent BV, defined as two or more episodes within six months, is common. The reasons for recurrence are not fully understood, but incomplete treatment or reinfection may be contributing factors. In cases of recurrent BV, longer courses of antibiotics or alternative treatments may be necessary.12

Prevention

Maintaining vaginal health requires a combination of healthy lifestyle choices and awareness of factors that can disrupt the vaginal microbiome. Douching should be avoided, as it disrupts the natural balance of bacteria in the vagina. Instead, the vagina is self-cleaning, and gentle, unscented soaps should be used externally. Wearing breathable, cotton underwear can help prevent excess moisture and maintain a healthy environment. Practicing safe sex by using condoms can also reduce the risk of bacterial imbalances and infections. A balanced diet, particularly one that includes probiotics found in yogurt and fermented foods, may also support a healthy vaginal microbiome.1,2,3,11

Emerging research suggests that probiotics, particularly strains of Lactobacillus, may help restore and maintain a healthy vaginal microbiome.13 Some studies indicate that oral or vaginal probiotics can reduce the recurrence of both BV and yeast infections by promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria. However, more clinical trials are needed to confirm their efficacy. In addition to probiotics, microbiome transplants are being explored as a potential future treatment for chronic vaginal infections. This experimental therapy involves transferring healthy vaginal microbiota to individuals with recurrent BV or other imbalances and holds promise as a targeted, long-term solution.2,3,5

Conclusion

Vaginal health is closely tied to the balance of the vaginal microbiome, which can be disrupted by various factors, including antibiotic use, hormonal changes, and lifestyle habits, as mentioned. Yeast infections and BV are two of the most common vaginal health issues, each requiring specific treatment and preventive strategies. As research on the vaginal microbiome progresses, we may see more personalised and effective treatments for maintaining vaginal health. Regular gynaecological check-ups and open communication with healthcare professionals are important for managing and preventing vaginal infections and promoting long-term wellbeing.5,9,11

References

1. Chen X, Lu Y, Chen T et al. The female vaginal microbiome in health and bacterial vaginosis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:631972

2. Lehtoranta L, Ala-Jaakkola R, Laitila A, et al. Healthy vaginal microbiota and influence of probiotics across the female life span. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:819958

3. Holdcroft AM, Ireland DJ, Payne MS. The vaginal microbiome in health and disease – what role do common intimate hygiene practices play? Microorganisms. 2023;11(2):298

4. Kalia N, Singh J, Kaur M. Microbiota in vaginal health and pathogenesis of recurrent vulvovaginal infections: A critical review. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2020;19(1):5

5. Jeanmonod R, Chippa V, Jeanmonod D. Vaginal candidiasis. Florida: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459317/

6. Health Service Executive. HSE Antibiotic prescribing: Candida genital thrush. Dublin: HSE; 2024. Available at: www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/2/gp/antibiotic-prescribing/conditions-and-treatments/genital/vaginal-candidiasis/

7. Satora M, Grunwald A, Zaremba B, et al. Treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis – an overview of guidelines and the latest treatment methods. J Clin Med. 2023;12(16):5376

8. Donders G, Sziller IO, Paavonen J, et al. Management of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: Narrative review of the literature and European expert panel opinion. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:934353

9. Sobel J, Vempati Y. Bacterial vaginosis

and vulvovaginal candidiasis

pathophysiologic inter-relationship. Microorganisms. 2024; 12(1):108

10. Kairys N, Carlson K, Garg M. Bacterial vaginosis. In: StatPearls [Internet].Florida: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459216/

11. Javed A, Parvaiz F, Manzoor S. Bacterial vaginosis: An insight into the prevalence, alternative treatments regimen and its associated resistance patterns. Microb Pathog. 2019;127:21-30

12. Health Service Executive. Antibiotic prescribing. Bacterial vaginosis. Dublin: HSE; 2024. Available at: www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/2/gp/antibiotic-prescribing/conditions-and-treatments/genital/bacterial-vaginosis/bacterial-vaginosis.html

13. Mollazadeh-Narestan Z, Yavarikia P, Homayouni-Rad A, et al. Comparing the effect of probiotic and fluconazole on treatment and recurrence of vulvovaginal candidiasis: A triple-blinded randomised controlled trial. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2023;15(5):1436-1446

Theresa Lowry Lehne RGN, PG Dip Coronary Care, RNP, BSc, MSc, PG Dip Ed (QTS), M Ed, PhD, Clinical Nurse Specialist/ANP, and Associate Lecturer, South East Technological University

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.