An overview of vaccination guidelines for hepatitis B in Ireland

Case reports

Paul is a 19-year-old gay man. He has been sexually active for two years. On the advice of his friends, he presented to the Gay Men’s Health Service for a routine sexual health screen. As part of his tests, he was screened for hepatitis A, B, and C. On review of his results, it became evident that he had no immunity to hepatitis A or B, so he was recalled for vaccination. He received three doses of a combined hepatitis A and B vaccine. Two months later he was recalled to see whether he had appropriate immunity. He had.

Tom is 47, and is a smoker in a larger body. He failed to mount an immune response to the standard hepatitis vaccination schedule. He received a double dose of vaccine at the same schedule and this time was successful.

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a double stranded DNA virus, a member of the Hepadnaviridae family. There are eight genotypes of HBV (A-H) with genotype A the predominant genotype in northwest Europe and North America. The whole virus consists of an inner core and an outer surface coat. The inner core contains genetic material (DNA), DNA polymerase, an enzyme essential for reproduction, the core antigen, and the e antigen. The outer surface coat contains the surface antigen.

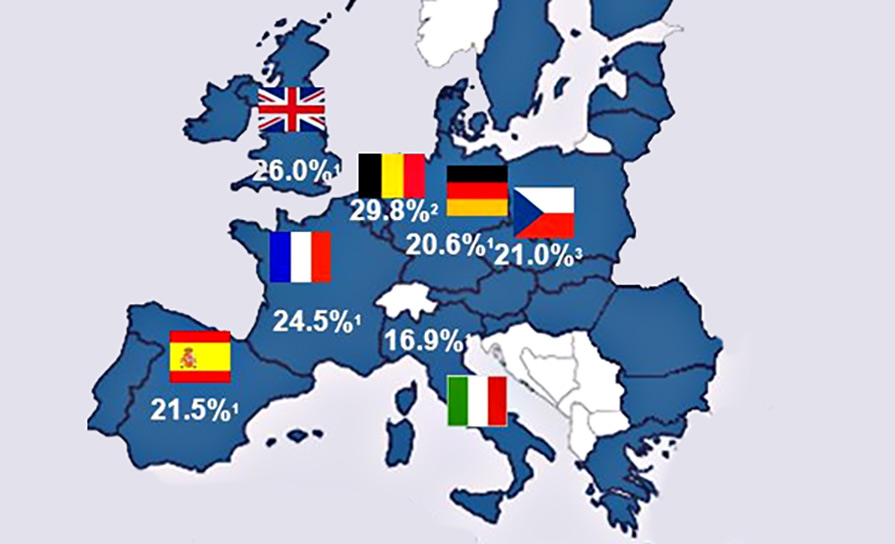

HBV infects more than 350 million people worldwide. It has an incubation period of 60-to-180 days. Of those infected, more than 90 per cent recover fully. In 2-to-5 per cent, the disease becomes chronic, as manifested by the persistence of the hepatitis B surface antigen for more than six months.

Chronic HBV infection may lead to the development of hepatic failure, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. It occurs in 5-to-10 per cent of symptomatic cases, but is higher in the immunocompromised, those with untreated HIV, those with chronic renal failure, and those on immunosuppressant drugs. It results in premature death in 15-to-25 per cent of individuals infected. All patients found to be HBsAg-positive (active HBV infection) should be referred to a hepatologist for further evaluation and consideration for treatment where appropriate. Patients with chronic HBV may have normal or minimally abnormal liver function. Many have few clinical manifestations of chronic liver disease, but may admit to fatigue or malaise. HBV infection is a notifiable disease to the Health Protection Surveillance Centre (HPSC).

Serology

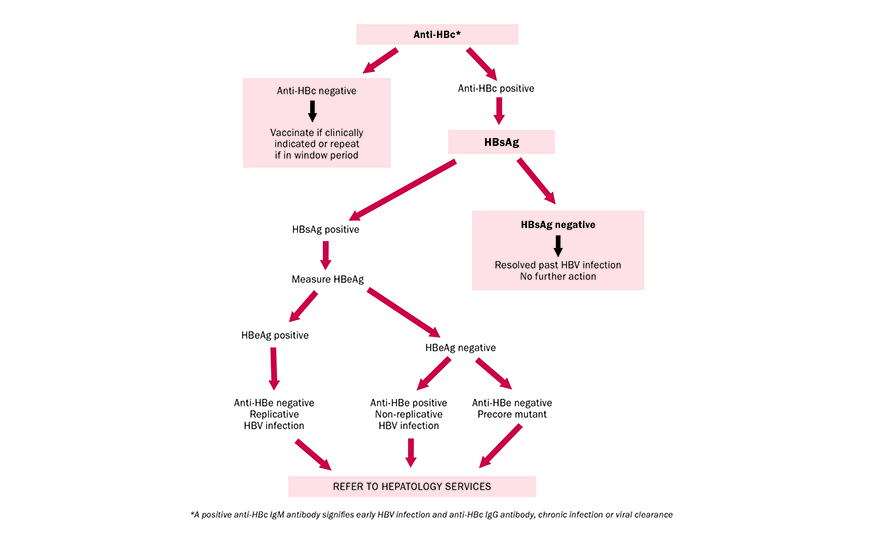

Serological markers of HBV are available to diagnose HBV. Testing determines whether the person is infected with HBV, and if so whether the infection is acute or chronic and if not infected, whether protective antibodies exist. There are three antigenic determinants associated with HBV infection – HBsAg, HBcAg, and HBeAg, and three corresponding antibodies – anti-HBs, anti-HBc, and anti-HBe.

- HBsAg: HBV surface antigen. This antigen appears in the blood from about six weeks after an acute infection usually before jaundice is clinically evident. It may disappear or persist. Its presence indicates current infection or a chronic infection, as well as a carrier state. The presence of HBsAg in the serum indicates active HBV infection and all HBsAg-positive persons should be considered infectious.

- Anti-HBs: HBV surface antibody. In persons who recover from HBV infection, HBsAg disappears from the blood and anti-HBs develops. Its presence in the serum indicates immunity from HBV infection following natural infection or vaccination.

- HBcAg: HBV core antigen. This antigen does not circulate in blood and does not appear on the laboratory results.

- Anti-HBc: HBV core antibody. This antibody appears at the onset of liver test abnormalities and persists for life. Acute or recently-acquired infection can be distinguished by the presence of immunoglobulin M (IgM) class of anti-HBc and can persist up to six months if the disease resolves.

- HBeAg: HBe antigen is only detected in serum of patients with acute or chronic infection. It is a measure of viral replication and infectivity. Its persistence correlates with the development of chronic liver disease and its loss correlates with low levels of replicating virus. Certain HBeAg-negative individuals have high measurable HBV DNA levels (viral genetic material), suggesting high viral turnover. This is due to a mutation in the precore region of the HBV genome and results in failure to produce HBeAg even in the presence of active viral replication. This is known as the ‘precore mutant’ HBV.

- Anti-HBe: HBV e antibody. This appears in the blood after the disappearance of HBeAg and correlates with low infectivity.

In the event of a positive HBsAg result, the National Virus Reference Laboratory (NVRL) will perform further serological tests; the HBeAg and the anti-HBe. These tests indicate the degree of infectivity or active viral replication. If the HBeAg is positive and the anti-HBe is negative, it suggests that there is active viral replication, that the patient is highly infectious, and the likelihood of viral clearance is small. Similarly, if the HBeAg is negative and the anti-HBe is positive, it suggests that the active infection will most likely clear, and the patient may recover fully.

FIGURE 1: Diagnostic algorithm for hepatitis B in high-risk populations such as IVDU/MSM

Vaccination

The HBV vaccine differs from the natural hepatitis virus in that the host (patient) is not injected with the complete hepatitis B virus, but with the yeast-grown recombinant spherical surface antigen. Because it is free of genetic material, which is in the core, it is not infectious and vaccination does not result in infection. The body, however, reacts against the HBsAg by making antibodies to this surface antigen so when natural exposure occurs, ie, the intact virus, the body recognises the surface antigen component of the virus and already has antibodies to hand to fight the infection immediately.

Anti-HBs on its own will only tell you the presence and the amount of anti-HBs. It will not differentiate between past natural exposure and vaccination. It is not a useful test on its own for differentiating between past natural exposure and the need for vaccination.

It has been recommended by the National Immunisation Advisory Committee (NIAC) that the following groups should receive hepatitis B vaccine if non-immune:

- Healthcare personnel: Doctors, nurses, dentists, midwives, laboratory staff, cleaning staff, general assistants, healthcare professionals, and anyone who is at particular risk through contact with blood, or;

- Anyone who is at particular risk through contact with blood or body fluids: The sexual partner’s family and household contacts of acute cases of HBV, families adopting children from countries with high prevalence of HBV, babies born to mothers with chronic HBV, people with haemophilia, and others requiring regular blood transfusions, patients with chronic renal failure with poor immunity and who may require dialysis, and patients with chronic hepatitis.

- Patients and family contacts: The sexual partner’s family and household contacts of acute cases of HBV, families adopting children from countries with high prevalence of HBV, babies born to mothers with chronic HBV, people with haemophilia and others requiring regular blood transfusions, patients with chronic renal failure with poor immunity, and who may require dialysis and patients with chronic hepatitis.

- Security and emergency services personnel.

- Susceptible members of high-risk groups: Individuals who may have multiple sexual partners, particularly homosexual and bisexual men (MSM) and sex workers, prisoners, tattoo artists, and immigrants from, or travellers to, areas with a high seroprevalence of HBV.

The contraindications to HBV vaccination include use in patients known to be hypersensitive to the vaccine, use in the presence of acute febrile illness, and known allergy to aluminium, the inactive ingredient of the vaccine.

Special precaution should be used in those with cardiac or pulmonary insufficiency, debilitation.

Facilities for management of anaphylaxis should be in place in the event of a serious hypersensitivity reaction occurring (see protocol for the management of anaphylaxis).

The vaccines should only be given when there is a doctor on site. In patients with thrombocytopaenia (low platelet count), bleeding disorder, on heparin or warfarin, vaccines may be administered subcutaneously. This route of vaccination may result in a sub-optimal response to the vaccine.

HBV infection in pregnant women may result in severe disease in the mother and chronic infection in the new-born. Immunisation should not be withheld from a pregnant woman if she is in a high-risk category (eg, active intravenous drug use, IVDU).

Common side-effects to the vaccine include mild transient local soreness, erythema, and induration at the injection site (occurs in up to half of the vaccine recipients), and fever, malaise, rash or flu-like symptoms – usually transient and usually responds to paracetamol.

Standard vaccination for HBV is at the elected date, one month later, and at six months. Guidelines recommend testing of anti-HBs two months after the course. In cohorts at risk of hepatitis C infection, MSM or IVDU, combined HBV and hepatitis A vaccines with the same protocol is recommended. In certain cases, for example after a known HBV exposure, a super accelerated vaccine course is recommended. This is one vaccine at the elected date, one at seven days, one at 21 days, and a booster at one year.

Non-responders

Following a three-dose course of HBV vaccine, however, 10-to-15 per cent fail to mount an adequate antibody response (non-responders). Booster injections are offered according to the initial response.

Failure to respond to hepatitis B vaccination means that the patient is not protected and in the event of a high-risk exposure, passive prophylaxis, passive immunisation is required. Clinical predictors of a poor response include:

- Male sex;

- Increased age (over 40);

- Increased BMI;

- Smokers;

- Immunodeficiency (eg, advanced HIV) or those on immunosuppressive therapy.

Anti-HBs (anti hepatitis B surface antibody) levels are measured as mIU/ml. The laboratory will report a level ranging from zero to >1,000.

- Zero or <10mIU/ml – non responder

Exclude past infection or chronic carriage by checking anti-HBc and HBsAg. These tests should have already been sent as a screening test on all patients presenting for vaccination for the first time.

Repeat a three-dose course of HBV vaccine (a different brand of vaccine should be considered). Alternatively, some patients who fail to respond to a three-dose course of a single vaccine may respond to a three double-dose course – one injection into each arm on at the elected date, at one month, and at six months.

- >10mIU/ml – adequate responder

No further action needed.

Antibody persistence

The duration of antibody persistence is not known and there is no current consensus on the need for booster doses. It is thought that the immune system will mount an anamnestic response, (has an effective immunological memory) by augmenting an antibody response to HBV exposure post adequate vaccination or prior natural infection. This means that if the antibody titre has declined with time and is barely detectable, the body will increase the level of these antibodies if required.

Dr Shay Keating, 254 Harold’s Cross Road, Dublin 6W

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.