An overview of the current prevalence of and elimination strategies for hepatitis B and C, and the impact on liver cancer rates in Ireland

In 2016, the World Health Organisation (WHO) adopted a Global Health Sector Strategy on viral hepatitis and set elimination targets for chronic viral hepatitis by 2030.1 The main targets are to reduce the incidence of hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) infections by 90 per cent, provide access to care for 80 per cent of treatment-eligible individuals, and achieve a 65 per cent reduction in mortality (compared with the 2015 baseline). Are we on track? How are we doing it?

In the last 10 years there has been a complete shake-up of the HCV paradigm. Current direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agents achieve a sustained viral response rate of over 95 per cent after eight or 12 weeks of treatment. The number of HCV patients developing end-stage liver disease and requiring a liver transplant is constantly reducing. Currently, HCV-positive organs are even considered for the pool of organ donation which, despite clinical and ethical controversies, has a very positive effect on reducing organ shortages. According to a retrospective review of the United Network for Organ Sharing in the US performed by Dhaliwal et al,2 from 2014 to 2017, 1.03 per cent (n:253) of liver transplants were performed with positive donors and negative recipients, and 6.73 per cent (n:1,650) with positive donors and positive recipients.

Nonetheless, the HCV landscape still faces huge challenges as many patients remain undiagnosed and there is still a subset of patients who struggle to engage with healthcare services and remain at risk of disease progression and development of liver cancer. According to the WHO,3 in 2015 just 7.4 per cent of those diagnosed with HCV infection had started treatment.

Micro elimination programmes have been the response. Healthcare providers have moved from the hospital to outreach clinics to facilitate HCV treatment and break barriers between service providers and patients. The cascade of HCV care has improved, with reduction in time from diagnosis to treatment, and in some countries, GPs have become the main prescribers of DAAs.

And what about HBV?

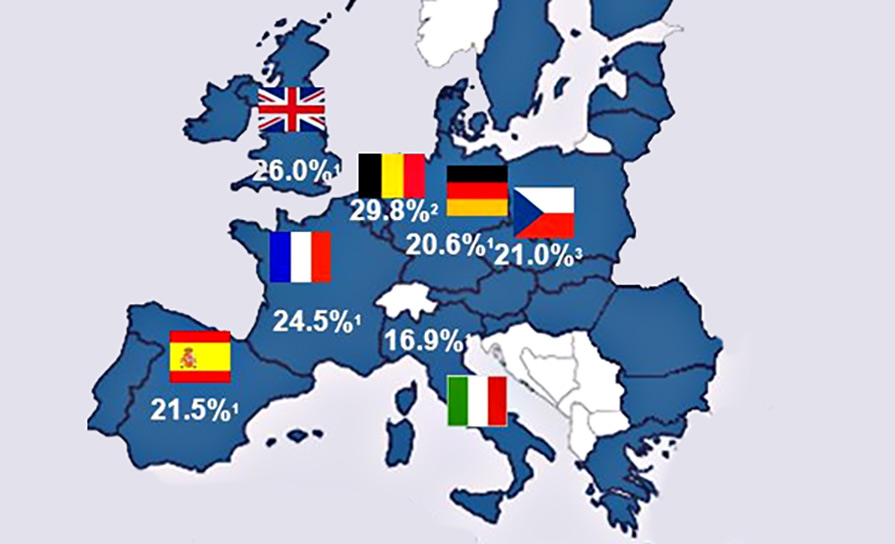

HBV these days affects more than 350 million people. Sub-Saharan Africa and southeast Asia are the regions with a higher prevalence (hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg) prevalence >8 per cent), while prevalence in Western countries remains low (HbsAg <2 per cent). Ireland is considered a low-prevalence country, although prevalence data in the general population is lacking. An antenatal HBV screening programme from an Irish maternity hospital reported a prevalence of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) of 0.35 per cent in the cohort of pregnant women.4

Most HBV infections occur during childbirth and childhood, and the earlier the infection arises, the higher the risk of it becoming chronic (neonatal transmission carries a 80-to-90 per cent risk of chronic infection, whereas this drops to 30 per cent during childhood). Universal vaccination is key in reducing transmission, but worldwide coverage with the initial birth dose vaccination is still low at 39 per cent.

HBV vaccine is known as the first anti-cancer vaccine, ever since universal infant vaccination in Taiwan demonstrated a significant reduction in hepatocellular cancer (HCC) incidence, because of reduction of its transmission. In Ireland it has been part of the primary immunisation schedule for infants since 2008.

In contrast, horizontal transmission of HBV during adulthood rarely becomes a chronic infection (<5-to-10 per cent). However, the probability of developing a symptomatic infection in the form of malaise, vomiting, high liver blood tests, and jaundice are higher (up to 30 per cent). Fulminant hepatitis accounts for less than 1 per cent of acute HBV infection in adults, but carries a mortality of around 80 per cent without liver transplantation.

Natural history of hepatitis B is dependent on the complex interplay between HBV replication and host immune response. It is characterised by four phases and the duration of each varies depending on age at the time of infection.

The decision to start treatment in immunocompetent patients is determined by three main factors: Fibrosis (assessed by biopsy or transient elastography), ALT levels, and HBV viral load. Treatment criteria differ for patients who are on chemotherapy, high-dose of steroids, etc, due to higher risk of HBV reactivation in this subset of patients. Estimates suggest that 15-to-25 per cent of patients living with HBV will require treatment. Current available treatments are interferon and nucleos(t)ide analogues (NA), but just a low fraction of patients achieve functional cure; that is long-term HBsAg loss (8-to-15 per cent after 48 weeks treatment and <10 per cent after five years, respectively). Third-generation NA, entecavir, and tenofovir, strongly suppresses HBV replication, but patients require long-term treatment due to high reactivation rates once NA is stopped.

Studies have shown a great impact of NA on chronic hepatitis B, with significant reduction in the incidence of cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, and HCC development. Despite the high potency of entecavir and tenofovir in achieving viral suppression, they do not act on HBV covalently closed circular DNA; thus, a residual risk of HCC remains.

Nowadays, there are multiple treatments in the pipeline for HBV cure, with new anti-HBV agents and an optimised combination of current regimens. New drugs for HBV cure include agents that directly target the virus life cycle, from inhibition of its entry or RNA translation, to agents that indirectly modulate the immune response, such as toll-like receptor agonists, therapeutic vaccines or immune checkpoint inhibitors. Translation inhibitors, such as small-interfering RNA and antisense oligonucleotides, have become the first to lead the race for a finite treatment and functional cure. Phase 3 trials have started the recruitment of patients this year, and plenty of developments are expected in the forthcoming years.

HCC

However, present-day HBV infection is challenged by HCC, as around half of the total liver cancer mortality is attributed to HBV. HCC is the sixth most common cancer and is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. In Ireland, data from the National Cancer Registry Ireland (NCRI) shows that liver cancer represented the sixth most common cause of male cancer-related death during the period 2018-2020.5 Five-year net survival during that period was 19 per cent; the second highest mortality after pancreatic cancer.

Data from Cancer Research UK not just highlights an increase in HCC mortality rates, which have more than tripled since the 1970s, but also an increase by almost half on the incidence rates over the last 10 years.6 This reflects an urgent need to improve HCC services in Ireland, which should start with clear and concise actions specifically targeted for HCC by the National Cancer Control Programme (NCCP) and be included in the next National Cancer Strategy 2027-2036.

The most important factor in HCC survival is its stage at diagnosis, as well as the fibrosis stage of the primary liver disease. In early stages, curative treatments, such as resection or radiofrequency ablation, provide five-year survival rates of 70 per cent, whereas in symptomatic advanced stages survival is one-to-1.5 years. Hence, low survival data from NCRI would suggest late diagnosis of HCC. This result would be in keeping with a retrospective study of patients attending the HCC clinic that we conducted in St Vincent’s University Hospital, Dublin.7 In the study, 23.1 per cent of patients with HCC secondary to chronic hepatitis B were diagnosed in early stages (BCLC 0 and A) and 70.9 per cent in advanced stages (BCLC B-D). During the study period 71.8 per cent of patients died.

In this total cohort of HCC patients registered at the Irish National Liver Transplant Unit, from January 2014 to August 2021, just 4.6 per cent of patients had HCC caused by HBV. Despite HCC-related HBV representing just a small fraction of HCC in Ireland, it affects a younger cohort of patients (in our study mean age was 54 years, while NCRI data cited the median age of males at diagnosis as 71 years and the median age of females as 74 years). Detection of HCC as part of an ultrasound screening programme, as well as having a previous diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B, were the only factors associated with an early-stage diagnosis, and subsequently with better survival.

Lack of awareness and barriers

Lack of awareness of HBV in the population from high endemic regions represents a huge barrier to care and to preventing devastating consequences of chronic hepatitis B, such as HCC. In a study from New Zealand, 40 per cent of a cohort with advanced HCC were not aware of their HBV diagnosis.8 In a similar study focused on African immigrants with HCC in New York City, Carr et al reported that 71 per cent were unaware of their HBV status when they presented with HCC.9

Chronic HBV, as well as chronic HCV, are known as silent liver diseases as symptoms develop late in their natural history once end-stage liver failure has developed or cancer-related symptoms have emerged. Moreover, usually at the time of infection, patients are asymptomatic. Hence, the importance again of diagnosing patients at risk of hepatitis B/C infection independently of their liver function tests.

HBV and HCV are well-known blood borne viruses and hence share some risk factors for infection, but in Ireland 80 per cent of patients with chronic HCV are previous or current drug users, whereas less than 1 per cent of chronic HBV are in this group.10 Consequently, the profile of patients affected with HBV and HCV is different and healthcare providers should be aware of which patients need to be screened for each of these chronic infections

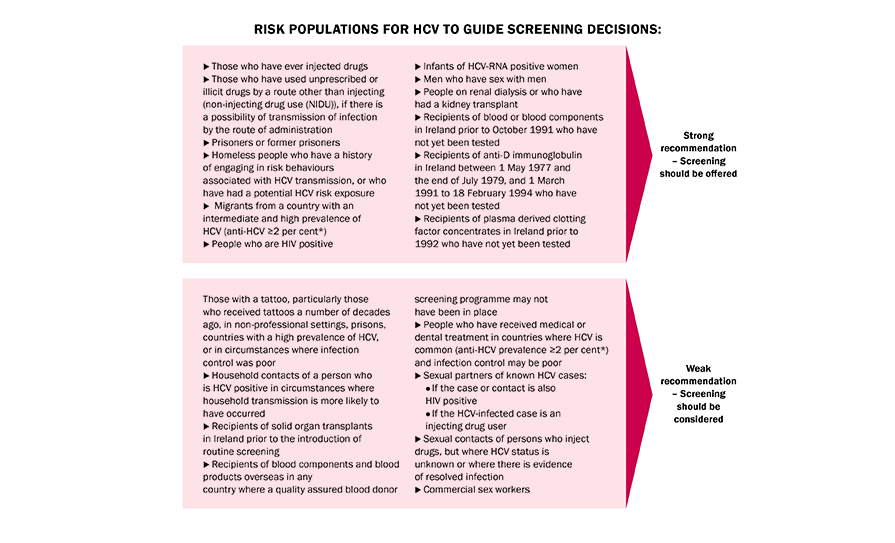

(see Figure 1: AASLD screening recommendations for hepatitis B, and Figure 2: Hepatitis C screening, National Clinical Guideline).

Other barriers have been reported that can lead to low HBV screening rates in high-risk populations, such as African or Asian immigrants. There are patient-related barriers (cultural beliefs, different language with healthcare provider, misconception that there is no treatment if diagnosed with chronic HBV), healthcare provider-related barriers (gaps in healthcare knowledge, underestimation of HBV risk, among others), and healthcare system-related barriers (economic, low numbers of specialised clinics, etc).

FIGURE 2: Hepatitis C Screening. National Clinical Guideline No 15 (Department of Health)12

In summary

It is important to learn from HCV knowledge: Hepatitis C has become an easy and effective to treat disease, but the population to target those treatments to is missing. Estimates from WHO suggest that just 20 per cent and 9 per cent of patients living with HCV and HBV, respectively, have been diagnosed. In the HBV field, resources should be focused not just on treatment development and research, but also on public health measures to increase awareness and knowledge of HBV, as well as facilitating screening, vaccination, and linkage to care.

Since last April, the Irish National Hepatitis C Treatment Programme in collaboration with SH:24 and the HSE have launched an online Hepatitis C Home Test platform (https://hepctest.hse.ie) for free HCV antibody testing. ‘Free test. Free cure.’ has been created to increase awareness, screening, and diagnosis of HCV. After completing an online questionnaire in relation to key HCV infection risk factors, the user gets a testing recommendation (testing is recommended or it is not). In the following two-to-four days a test kit arrives at the user’s doorstep. Outcomes of this screening strategy are not available yet, but so far over 3,000 tests have been delivered. Similar innovative strategies are needed to identify patients with hepatitis B in Ireland.

Diagnosis at early stages of HCV and HBV infections and linkage to appropriate care reduces incidence (preventing future infections), morbidity, and mortality. To achieve the 2030 WHO hepatitis elimination goals we need to work together with all stakeholders involved.

At-risk populations for HBV (to guide screening decisions)

- Persons born in regions of high or intermediate

HBV endemicity (HBAg prevalence of ≥2 per cent)

- Africa (all countries)

- North, Southeast, East Asia (all countries)

- Australia and South Pacific (all countries except Australia and New Zealand)

- Middle East (all countries except Cyprus and Israel)

- Eastern Europe (all countries except Hungary)

- Western Europe (Malta, Spain, and indigenous populations of Greenland)

- North America (Alaskan natives and indigenous populations of Northern Canada)

- Mexico and Central America (Guatemala

and Honduras)

- South America (Ecuador, Guyana, Suriname, Venezuela, and Amazonian areas)

- Caribbean (Antigua-Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Haiti, Jamaico, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia,

and Turks and Caicos Islands)

- US-born persons not vaccinated as an infant

whose parents were born in regions with high HBV endemicity (>8 per cent)*

- Persons who have ever injected drugs*

- Men who have sex with men*

- Persons needing immunosuppressive therapy, including chemotherapy, immunosuppression related to organ transplantation, and immunosuppression for rheumatological or gastroenterologic disorders

- Individuals with elevated ALT or AST of

unknown etiology*

- Donors of blood, plasma, organs, tissues, or semen

- Persons with end-stage renal disease, including predialysis, hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and

home dialysis patients*

- All pregnant women

- Infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers*

- Persons with chronic liver disease, eg, HCV*

- Persons with HIV

- Household, needle-sharing, and sexual contacts

of HBsAg-positive persons*

- Persons who are not in a long-term, mutually monogamous relationship (eg, >1 sex partner

during the previous six months)

- Persons seeking evaluation or treatment for

a sexually-transmitted disease*

- Healthcare and public safely workers at risk for occupational exposure to blood or blood-contaminated body fluids*

- Residents and staff of facilities for developmentally disabled persons*

- Travellers to countries with intermediate or high prevalence of HBV infection*

- Persons who are the source of blood or body fluid exposures that might require post-exposure prophylaxis

- Inmates of correctional facilities*

- Unvaccinated persons with diabetes who are aged 19 through 59 years (discretion of clinician for unvaccinated adults with diabetes who are aged ≥60 years)*

References

World Health Organisation. Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis 2016-2021. Towards ending viral hepatitis. 2016. Available at: www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIV-2016.06

Dhaliwal A, Dhindsa B, Ramai D, Sayles H, Chandan S, et al. Impact of utilisation of hepatitis C positive organs in liver transplant: Analysis of united network for organ sharing data base. World J Hepatol. 2022 May 27;14(5):984-991

World Health Organisation. Global Hepatitis Report. 2017. Available at: www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565455

Cafferkey MT, Beckett M, Butler KM, Cahill I, Dooley S, Hall WW, et al. Antenatal hepatitis B screening: Is there a need for a national policy? Ir Med J. 2001 Apr;94(4):111–2

National Cancer Registry Ireland. Cancer in Ireland 1994-2020: Annual Statistical Report of the National Cancer Registry. 2022. Available at: www.ncri.ie/publications/statistical-reports/cancer-ireland-1994-2020-annual-statistical-report-national-cancer

Cancer Research UK. Liver cancer statistics. Accessed May 2023. Available at: www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/liver-cancer

Sopena-Falco J, McCormick A, MacNicholas R, Houlihan D, Bourke M, Feeney E. Hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Screening, screening, and more screening. IMJ. 2023 Apr;116(4):756

Mules T, Gane E, Lithgow O, Bartlett A, McCall J. Hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma presenting at an advanced stage: Is it preventable? N Z Med J. 2018 Nov 30;131(1486):27–35

Carr J, Cha D, Shaltiel L, Zheng S, Siderides C, et al. African Immigrants in New York City with hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma demonstrate high morbidity and mortality. J Immigr Minor Health. 2022 Apr;24(2):327-333

Murphy N, Thornton L, O’Donnell K, Igoe D, Barry J, Bourke M, et al. Drug-related bloodborne viruses in Ireland 2018. Health Protection Surveillance Centre. 2018. Available at: www.hpsc.ie/a-z/hepatitis/injectingdrugusers/publications/Drug-related%20bloodborne%20viruses%20in%20Ireland,%202018.pdf

Terrault N, Bzowej N, Chang K, Hwang K, Jonas M, et al. AASLD guidelines for treatment of hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016 Jan; 63(1):261-83 Department of Health. Hepatitis C Screening. NCEC National Clinical Guideline No 15. 2017. Available at: https://assets.gov.ie/11574/f02459434e3f40ec8596c6494a6f8423.pdf

Dr Julia Sopena Falco, Locum Consultant in Hepatology, National Liver Unit, St Vincent’s University Hospital, Dublin

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.