An outline of the latest national and international guidelines on the diagnosis and management of HCV

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major cause of chronic liver disease worldwide, with approximately 71 million people chronically infected worldwide, leading to 400,000 deaths annually due to cirrhosis complications and liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma). In Ireland, the Health Protection and Surveillance Centre (HPSC) estimates that between 20,000 and 30,000 people are infected with hepatitis C, and of those, approximately 10,000 have been diagnosed, though this figure is disputed by some of the hepatology clinical community.

In 2016, the World Health Organisation (WHO) adopted the first Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis, calling for its elimination as a public health threat. The strategy presented a target for 2030 – of reducing new HCV infections by 80 per cent and mortality by 65 per cent. All WHO Member States, including Ireland, have approved this strategy. One of the major difficulties in eradicating HCV is that significant numbers of patients are unaware of their infection and remain undiagnosed.

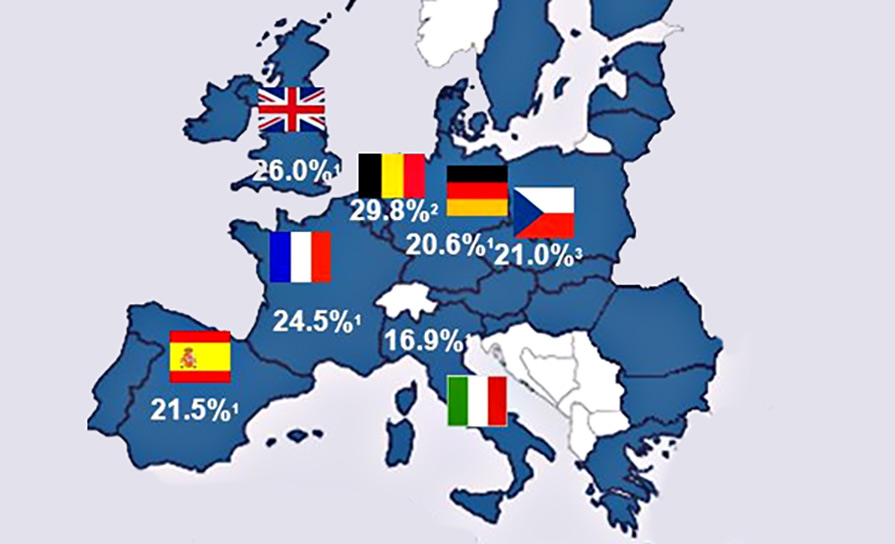

Thus key to the eradication goal is actively seeking out undiagnosed HCV cases; healthcare providers should screen individuals with risk factors, and providing free, widely available access to direct acting antivirals (DAAs), which can cure more than 95 per cent of cases and dramatically reduce long-term complications, like liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma, with minimal side-effects. In June 2019, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) published the EASL Policy Statement on Hepatitis Elimination. In so doing, EASL called on all European countries to implement a six-step action plan based on the WHO’s 2030 elimination targets, to develop a national strategy to increase public awareness, provide robust education to care providers at all levels, offer testing, and provide links to care.

At the end of 2019, EASL and three other health associations also joined forces in a call-to-action initiative: Calling to simplify HCV testing and access to treatment, integrating them with primary care and other disease programmes.

The call-to-action document outlines four clinical strategies that liver disease associations and their constituents can use in their continuing HCV elimination efforts, including simplifying diagnostic and treatment algorithms, integrating HCV treatment with primary care and other disease programmes, decentralising HCV services to local level care and task-sharing care with primary care clinicians and other healthcare practitioners.

The call-to-action also highlights the efficacy of existing screening and treatments, including accurate rapid HCV antibody screening and confirmatory viral load testing that can be accomplished in a single clinical visit and pan-genotypic DAAs that are available in fixed dose combinations. In 2018, EASL first published comprehensive clinical practice guidelines, EASL Recommendations: Treatment of Hepatitis C, to assist physicians and other healthcare providers, as well as patients and other interested individuals, in the clinical decision-making process, by describing the current optimal management of patients with acute and chronic HCV infections.

These recommendations were updated in September 2020 (final update of the series), and can be summarised as follows:

What is new in this final version of the EASL recommendations?

First of all, there are clear recommendations for the diagnosis of the infection, as well as for screening in order to link-to-care as many infected subjects as possible. Classically, the diagnosis of the HCV infection is based on the detection of anti-HCV antibodies followed by confirmation of the presence of the virus by a molecular, generally polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based, technique. HCV core antigen testing can be used as an alternative to RNA testing by PCR. For screening, the classical serum or plasma ELISA can be replaced by a whole-blood ELISA on dried blood spots, or by a rapid diagnostic test performed on serum, plasma, whole blood, or even saliva. Reflex testing for confirmation of replication is recommended to simplify and shorten access to treatment.

Once the diagnosis has been made, all subjects with recently acquired or chronic hepatitis C who are naïve to treatment or treatment-experienced (interferon, ribavirin and/or sofosbuvir) should be treated without delay.

Pangenotypic combinations of two direct-acting antivirals (sofosbuvir/velpatasvir or glecaprevir/pibrentasvir) should be preferred in the therapeutic indication. Today, the majority of patients should have access to a simplified treatment, without prior determination of the HCV genotype and subtype.

What is required to start antiviral therapy of hepatitis C?

Only three pieces of information are necessary for treatment initiation, according to the revised guidelines: Proof of viral replication (presence of RNA or core antigen), determination of the presence or absence of cirrhosis by a non-invasive test (possibly APRI or FIB-4, which are easily accessible), and the study of possible drug-drug interactions.

In this case, patients may be treated with sofosbuvir/velpatasvir for 12 weeks, or with glecaprevir/pibrentasvir for eight weeks if they have no cirrhosis or if they have cirrhosis and are treatment-naïve and 12 weeks if they have cirrhosis and a history of treatment failure. “This simplified approach results in very high sustained virological response rates and, above all, easy access to treatment for a very large number of patients. It is a key option for achieving the WHO elimination targets,” said EASL.

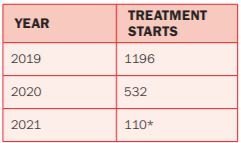

*End of March 2021

In specialised departments, it remains advisable to perform HCV genotype and subtype determination in order to offer cirrhotic subjects infected with HCV genotype 3 an enhanced treatment to optimise their response rates, the revised guidelines note. HCV genotype and subtype determination is also very important in regions where HCV subtypes inherently resistant to NS5A inhibitors are frequently found in infected subjects, or in industrialised countries in subjects originating from these regions.

However, such determination should be based on sequence analysis (because hybridisation-based assays cannot discriminate these subtypes), which is not available in many places. In the absence of reliable data with the most recent ‘pangenotypic’ dual therapies for most of these subtypes, it is recommended to treat them with the triple combination sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir as first-line therapy (subtypes 1l, 4r, 3b, 3g, 6u, 6v or any other subtype that naturally harbours polymorphisms conferring reduced susceptibility to NS5A inhibitors).

What is new on the treatment of patients who failed previous antiviral therapy?

Retreatment of patients who failed to achieve viral eradication after an NS5A or protease inhibitor-containing regimen is based on a triple combination of sofosbuvir, velpatasvir and voxilaprevir. In the most difficult-to-cure patients (advanced cirrhosis, multiple treatment failures, presence of complex resistance-associated substitution profiles), the use of the combination of sofosbuvir plus glecaprevir/pibrentasvir provides a better barrier to resistance to NS5A inhibitors. Treatment can also be reinforced by adding ribavirin and/or extending its duration to 16 or 24 weeks in the most problematic subjects.

What do the updated recommendations mean for the treatment of particular patient groups?

The treatment of many particular HCV-infected groups has been updated in this final version of the recommendations. An important novelty concerns paediatric treatments for which clear indications are given, pending the approval of the corresponding drug formulations. The treatment of adolescents is identical to that for adults. The treatment of HCV during pregnancy is also discussed (but not recommended in the current state of knowledge).

Other special groups that are discussed include patients with decompensated cirrhosis, those with hepatocellular carcinoma, solid organ (including liver) transplant recipients, patients who inject drugs and subjects under opioid substitution, and incarcerated subjects. The specific problem of certain co-morbidities (manifestations of HCV related to the formation of immune complexes, patients with renal impairment, co-infection with the hepatitis B virus, hemoglobinopathies and coagulation disorders) is also covered.

Source: https://easl.eu/publication/easl-recommendations-on-treatment-of-hepatitis-c-2020/

Ireland: National Hepatitis C Treatment Programme

The HSE’s National Hepatitis C Treatment Programme (NHCTP) was established in 2015, and is supported by a Clinical Advisory Group (CAG) and a Programme Advisory Group (PAG). All prescribing clinicians are entitled to membership of the CAG, which concurs with international guidelines and adopts the recommendations as best-practice in the Irish setting. Almost 6,000 people with HCV have been successfully treated with DAAs through the programme to-date.

Offered through designated hospital clinics initially, in 2017 DAA treatment was successfully expanded to the drug treatment service with on-site dispensing. In 2019 a community prescribing and dispensing pilot programme (GPs and pharmacists) was initiated, with new guidelines published by the ICGP and updated in July 2020. Although the preferred treatment route remains through one of the eight hospital-based treatment centres, community treatment may be preferred if patients find it difficult to attend the hospital based services for logistical, social or psychological reasons, the guidelines note. For the present, community treatment is restricted to low-risk patients.

Patients with cirrhosis, organ transplantation, HIV and recurrent HCV infection should be referred to a hospital treatment centre. It is expected that these criteria may change over time. Speaking in 2020, Clinical Director of the Programme, Prof Aiden McCormick, Consultant Hepatologist, St Vincent’s University Hospital, Dublin, said Ireland had achieved the interim WHO elimination targets for 2020, and appeared “to be on target to achieve the 2030 elimination targets. More robust metrics will be required to confirm we are achieving this.

The targets will only be achieved if we can identify the majority of infected patients in the country, which requires buy-in from all healthcare providers. Eradication will also require intensification of public health preventative measures, including needle exchange, etc, to prevent new infections and re-infections. It is a goal which can and should be achieved in Ireland.”

For more information, visit www.hse.ie/hepc. Any GPs wishing to become involved in treatment should contact the NHCTP at nhctp@hse.ie

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.