In December 2016, a report was published by the National Cancer Registry Ireland (NCRI) showing that the number of patients with ‘primary liver cancer’ had increased by over 300 per cent in the 21-year period from 1994 to 2014. This is perhaps unsurprising, given that hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) arises almost entirely in patients with liver cirrhosis and Ireland is currently facing a growing epidemic of deaths related to advanced liver disease. The publication of this report just before Christmas was particularly apt, given that the sharp rise in liver cirrhosis is attributable to obesity and excess alcohol consumption in this country. This review looks critically at the current state of liver disease in Ireland and the climbing incidence of HCC, drawing on relevant comparisons to the UK. We discuss the management structures and pathways established to triage and manage patients with a new diagnosis of HCC. Finally, we examine the Irish healthcare infrastructure, which is struggling to deal with an epidemic of liver disease.

<h3 class=”subheadMIstyles”>Background and epidemiology</h3>

The incidence of HCC is rising globally. This is perhaps unsurprising, given deaths from liver cirrhosis have increased steadily over the past 30 years, exceeding one million worldwide in 2010. Deaths from liver cirrhosis are slowly declining in Western Europe, with the exception of the UK, Ireland and Finland, where cirrhosis mortality rates have continued to increase since the late 1980s. Liver disease is now one of the five ‘big killers’ in England and Wales, alongside heart disease, cancer, strokes and respiratory disease. Additionally, the Office of National Statistics in the UK has described liver disease as the third-biggest cause of premature mortality, as many patients die from liver disease during working age (18-to-65 years). In contrast to the other ‘big killers’, however, deaths from liver disease in the UK are rising sharply (Figure 1). Patients with established cirrhosis have a 1-to-5 per cent cumulative annual risk of developing HCC. Surveillance strategies, including a targeted liver ultrasound (US) and alpha feto-protein (AFP) measurement every six months, are recommended by European and American guidelines for these patients.

Sadly, the situation in Ireland mirrors that of the UK. A recent analysis of data from Ireland’s Hospital in-Patient Enquiry (HiPE) scheme has revealed that the rate of hospital admissions for alcoholic liver disease increased by 247 per cent between 1995 and 2007 in Ireland. Similarly, deaths from alcohol-related liver disease have almost doubled over the same time period. Concurrently, Ireland is facing an epidemic of obesity. It has been predicted that we will be the most obese nation in Europe by 2030. The majority of the obese population will have non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and many (up to one-in-20 of the Irish citizens) will have ongoing inflammation and scarring, which ultimately leads to cirrhosis. Of those patients with cirrhosis, 5-to-10 per cent will get liver cancer during their lifetime. It is not surprising, therefore, that the number of HCC diagnoses are rising in parallel with the increase in liver cirrhosis over the past decade.

<h3 class=”subheadMIstyles”>Diagnosis and management of HCC in Ireland</h3>

HCC is a vascular tumour and as such, demonstrates typical characteristics on contrast-enhanced imaging, ie, CT or MRI. A nodule in a cirrhotic liver, which hyper-enhances during the arterial phase and demonstrates washout on the portal venous and delayed phases, meets non-invasive criteria for the diagnosis of HCC. Such lesions do not require biopsy to establish a definite diagnosis of HCC. Notably, the NCRI database is comprised primarily of biopsy-proven tumours, suggesting that the real incidence of HCC in Ireland is significantly underestimated.

There is currently no mention or plan for HCC in the recently-published <em>National Cancer Strategy 2017-2026</em>.

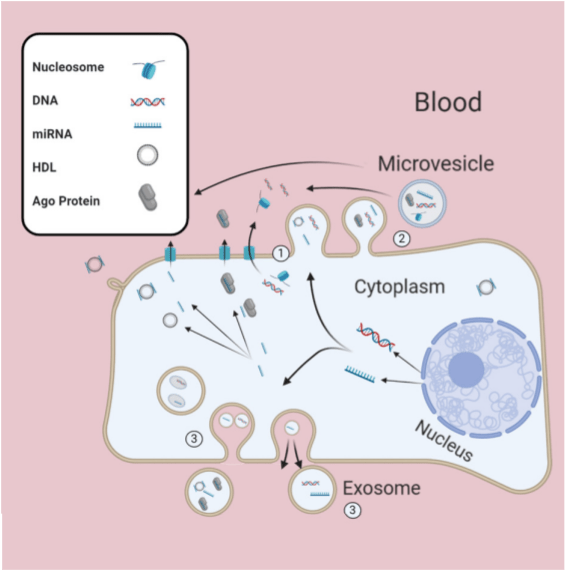

In 2014, a dedicated HCC clinic was established in St Vincent’s University Hospital (SVUH), Dublin, to deal with the growing number of HCC referrals to our centre. Between January 2014 and December 2016, there were 278 patients newly diagnosed with HCC at SVUH alone. Predictably, over 90 per cent of the patients referred had established cirrhosis most frequently caused by viral hepatitis, alcohol, NAFLD, and autoimmune liver disease. All cases referred to our unit are discussed at the weekly radiology multidisciplinary meeting, where a firm diagnosis of HCC is established and different treatments are discussed. The treatment for this cancer is guided by the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system (Figure 2). This staging system considers both tumour burden and the stage of the underlying liver disease, ie, the level of liver function and patient performance status. Treatment options range from curative to palliative and supportive therapies. Curative options include liver transplantation, liver resection and thermal ablation (radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and microwave ablation (MWA)). Non-curative options include transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE), selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) and sorafenib, an oral chemotherapeutic agent. Each of these therapies has proven survival benefit. Some patients may be eligible for a combination of these treatments, depending on their tumour burden and performance status.

<h3 class=”subheadMIstyles”>Treatments for HCC offered in SVUH</h3>

The number and volume of different treatments administered to patients with HCC in SVUH are captured in Table 1. Treatment for HCC can be broken down into four categories: Surgical therapy; loco-regional therapy; chemotherapy; and supportive and palliative treatments. These will be briefly reviewed here.

<strong><em>Surgical options</em></strong>

When considering the best treatment for patients with HCC, the presence of liver cirrhosis, with or without liver decompensation, must be considered. Resection is usually reserved for solitary tumours located in a favourable position. The presence of portal hypertension or poor synthetic function increases the risk for liver failure following surgery. Following successful surgery, there is a risk of developing <em>de novo</em> tumours in the background cirrhotic liver and ongoing surveillance is therefore required. Liver transplantation (LT) offers a predicted five- and 10-year survival of 80 per cent and 70 per cent, respectively. Patients must fulfil strict criteria (a single HCC ≤5cm, or no more than three HCCs each ≤3cm, and a serum AFP level <1,000kU/l) to be considered eligible for LT.

Those patients who are deemed appropriate candidates for LT go through a series of testing to assess their mental and physical ability to withstand the operation and transplantation process.

<strong><em>Locoregional therapy</em></strong>

Locoregional therapy for HCC can be delivered in a number of ways, including thermal ablation, TACE and SIRT. These techniques are available and carried out weekly in the Interventional Radiology (IR) Department in SVUH, under the care of a consultant interventional radiologist and their team. Thermal ablation refers to the use of heat energy to burn and kill the cancer cells. This can be done in the form of RFA and MWA, performed under general anaesthesia. The treatment is suitable for small solitary tumours only. TACE is used to deliver drug-eluting beads impregnated with chemotherapy into the arterial blood supply feeding the tumour, as well as blocking-off this blood supply. It is performed under conscious sedation. The aim is that the tumour becomes necrotic and dies. TACE is primarily used for patients with HCC who are BCLC stage B, but can also be used as a bridging therapy for those patients with earlier-stage disease awaiting LT. SIRT is a similar technique to TACE but delivers microscopic radioactive beads into the arterial blood supply feeding the tumour. The beads become permanently lodged in the small blood vessels of the tumour and emit radiation for several weeks or months after the treatment. The radiation destroys the tumour cells from within, with minimal impact to the surrounding healthy liver tissue.

<strong><em>Systemic chemotherapy and palliation</em></strong>

Sorafenib is the only systemic chemotherapeutic agent shown to have any impact on overall survival. Patients with HCC BCLC stage C, with compensated liver cirrhosis are offered this form of therapy. These patients are reviewed monthly in the dedicated HCC clinic and assessed for side-effects. Their management requires a good working relationship with their local GP and community-based nursing teams. If a patient is deemed to be BCLC stage D, ie, poor performance status with advanced liver disease, they are cared for in conjunction with palliative services. Supportive therapy includes symptom management for pain, nausea and encephalopathy, as well as endoscopy for variceal surveillance and escalation of diuretic dose and/or large-volume paracentesis for the management of ascites.

<h3 class=”subheadMIstyles”>Prognosis of patients with HCC</h3>

The NCRI report evaluates patient survival over a 20-year period and concludes that survival from liver cancer is poor. The latest estimate of five-year net survival in Ireland was just 17 per cent. These data contrast sharply with our experience in SVUH, where survival depends upon stage at presentation. In January 2014, a prospective database of all new referrals to the HCC clinic at SVUH was established. We analysed the survival probability, depending upon BCLC stage at the time of referral. In total, we had a complete dataset on 274 patients (BCLC stage 0 (n=18), A (n=112), B (n=68), C (n=40) and D (n=36)). A survival curve was generated to estimate the actuarial survival probability of each patient type over the study period. At the end of follow-up, the proportion of patients alive in each of the groups were as follows: BCLC stage 0 — 94.4 per cent; A — 77.7 per cent; B — 58.8 per cent; C — 45 per cent; and D — 25 per cent. The predicted median survival time for BCLC stage A, B, C and D patients was 66, 26, seven and one month, respectively. This data highlights the importance of appropriate screening strategies (US liver and AFP level every six months) for all patients with liver cirrhosis, and early detection of cancers. In our experience, the minority of patients with HCC (<40 per cent) were referred from outside the Dublin area and sadly, only 19 per cent of these cases were at a stage to be offered curative therapy. These cases were generally referred at an advanced stage of disease. In contrast, over 60 per cent of the referrals from within the Dublin area were at an early stage (>50 per cent) and suitable for curative therapy.

<h3 class=”subheadMIstyles”>Tackling liver disease and HCC in Ireland</h3>

The epidemic of liver disease and rising incidence of HCC needs to be tackled in a number of ways. Firstly, as described previously, liver cirrhosis is a silent condition and often progresses until patients develop signs or symptoms of liver failure. Frequently, at this stage it is difficult to reverse the liver disease and/or treat the HCC, which is all too often at an advanced stage. GPs are perfectly positioned to identify patients with emerging cirrhosis. Screening and early identification of these patients is undoubtedly cost-effective and will save lives. To this end, there are a variety of non-invasive scoring systems that can be used to identify patients with fibrosis and cirrhosis in the community. For example, Fibrosis 4 (Fib4), aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index (APRI), and the NAFLD fibrosis scores use the basic blood tests, including AST and ALT values, INR and platelet count, and give a reasonable indication as to the presence of fibrosis or cirrhosis. Where there is a concern, patients should be referred to the local hepatology service for a FibroScan (US-based technology) that can reliably measure liver stiffness and thereby exclude or confirm the presence of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis.

Secondly, there is a significant lack of trained hepatologists and specialist-trained liver nurses in the vast majority of Irish hospitals. There is an urgent need to create a number of dedicated hepatology centres in selected hospitals around the country. Each centre would be staffed with a dedicated hepatologist, radiologist and clinical nurse specialists. The hepatology unit would act as a referral centre for inpatient transfers (decompensated cirrhotic, variceal haemorrhage, acute severe hepatitis) and outpatient referrals (patients with progressive fibrosis and cirrhosis) from primary care and local hospitals. These centres would have the appropriate skill set to deal with liver emergencies, including bleeding oesophageal and gastric varices and reliably diagnose and deliver selected therapies to patients with HCC. These designated hepatology centres would feed data directly into a national cirrhosis registry, ensuring appropriate HCC screening is carried out, allowing early detection of HCC and thereby improving overall patient survival. The cost of implementing such a strategy would be significantly offset by preventing progression of liver disease and development of HCC, leading to a lesser requirement for LT and various other treatment modalities.

Thirdly, dramatic public health interventions are required to curb the rise in liver disease. A Public Health (Alcohol) Bill was introduced by the then Minister for Health Leo Varadkar in 2015 and passed all stages of the Seanad at the end of last year. The Bill proposed a suite of initiatives aimed at reducing harmful drinking in Ireland. The Bill includes five main provisions: 1) Minimum unit pricing; 2) health labelling of alcohol products; 3) regulation of advertising and sponsorship of alcohol; 4) structural separation of alcohol products in mixed trading outlets; and 5) regulation of the sale and supply of alcohol in certain circumstances. It is imperative that each part of this Bill is implemented in the short term. There is also a requirement to formally tackle the growing epidemic of obesity in Ireland. Promotion of healthy lifestyles to reduce obesity in the country and its results on health; Governmental regulations to reduce sugar content in food and drink; and use of new diagnostic pathways to identify people with NAFLD are critical elements of such a strategy. <strong></strong>

Significant progress has been made in the treatment of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) over the past three years in Ireland. This followed the arrival of new, curative, direct-acting antiviral (DAA) medications and the establishment of an effective treatment infrastructure, funded by the Department of Health and HSE, in late 2014. To date, over 2,000 patients have been treated in Ireland. Total eradication of infections from chronic HCV in Ireland by 2025 will pose additional challenges, including identification and treatment of silent infection and ‘difficult-to-treat’ groups. Finally, there is an urgent need for increased awareness of liver disease in the general population with a national campaign led by the HSE, supported by the regional specialist hepatology centres.<strong></strong>

<h3 class=”subheadMIstyles”>Conclusions</h3>

Deaths from liver disease and HCC are increasing at an alarming rate in Ireland. The current healthcare infrastructure is ill-prepared to deal with this epidemic. There is an urgent need to develop a national strategic plan to tackle this. We would strongly support the development of dedicated regional hepatology centres. These centres would not only deal with the acute complications of liver failure, but also establish registries for patients with a diagnosis of cirrhosis. Appropriate surveillance of these patients will translate into earlier detection of HCC and improved patient survival.

<p class=”referencesonrequestMIstyles”><strong>References on request</strong>

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.