<h3><strong>Introduction </strong></h3>

Myeloma is one of the great success stories of modern haemato-oncology. The survival of patients has greatly improved over the last 20 years, firstly following the introduction of autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), and thereafter following the development of two new drug classes, proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib, carfilzomib, ixazomib) and immunomodulatory drugs (thalidomide, lenalidomide and pomalidomide).

For younger transplant-eligible patients, the median survival is currently approximately eight years. In parallel, refinements in diagnostic criteria and prognostic markers have facilitated the application of more risk-stratified approaches. For many patients, myeloma is therefore a chronic disease, albeit a malignancy, and the model of patient care is increasingly one of chronic disease management.

Despite these advances, myeloma remains an incurable malignancy of plasma cells, which accounts for approximately 10 per cent of all haematological malignancies in international registries.

According to the <em>Multiple Myeloma Cancer Factsheet</em> of the National Cancer Registry Ireland (NCRI) (May 2017), the annual incidence of myeloma in Ireland is 7.1 per 100,000 in men and 4.1 per 100,000 in women and a total of 271 new cases are diagnosed here every year. In general, the median age at diagnosis is around 70 years and, in a large Mayo Clinic series, 15 per cent of patients were below the age of 50 years. The NCRI found that the survival rate at five years had improved from 27.5 per cent (1994-1998) to 49.6 per cent (2009-2013) and that the estimated 10-year survival is 30.2 per cent.

<div style=”background: #e8edf0; padding: 10px 15px; margin-bottom: 15px;”>

<strong>Case Study</strong>

A 57-year-old schoolteacher had increasing mid-back discomfort over three months. One weekend, she developed a fever and a cough productive of green sputum, and her partner found her to be confused. She was brought to the GP, who referred her to the local emergency department. On presentation, she was disoriented, febrile to 38.5 degrees and had bilateral crepitations on auscultation. A chest x-ray revealed pneumonia. She was anaemic (Hb 10g/dl), had an elevated creatinine (140umol/l) and was hypercalcaemic (3.1mmol/l). Her total protein was 99g/L (66-87) and albumin 32g/l (35-to-50). She was rehydrated, commenced on intravenous antibiotics and treated for hypercalcaemia.

Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) detected an IgG kappa paraprotein of 45g/L and kappa light chains were present in her urine. She was referred to the haematology service with probable myeloma. There was an infiltrate of plasma cells on her bone marrow aspirate and an urgent CT scan of her spine revealed multiple thoracic vertebral compression fractures. Fluorescent <em>in situ</em> hybridisation (FISH) cytogenetic analysis detected the translocation, t(4;14).

She was started on treatment with the combination of oral cyclophosphamide, subcutaneous bortezomib and oral dexamethasone. Following discharge six days later, she went on to attend the day ward on a weekly basis over the next four months. Her paraprotein was 9g/L following completion of this induction therapy. As she had no significant medical history, she had been referred for stem cell collection. These were harvested by leukapheresis and she proceeded to an autologous stem cell transplant. The transplant admission lasted three weeks and was complicated by infection, mucositis and hair loss. At her assessment three months’ post-transplant, the paraprotein has fallen further to 2g/L, consistent with a further deepening of her remission. She was then commenced on maintenance treatment with oral lenalidomide and further follow-up consisted of once-monthly visits for clinical review, laboratory tests, her high-tech prescription for lenalidomide and an intravenous bisphosphonate for bone protection.

</div>

<h3><strong>MGUS</strong></h3>

Symptomatic myeloma requiring treatment evolves from the pre-malignant condition, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), although this asymptomatic precursor state has often gone undetected prior to the diagnosis of myeloma. MGUS is present in 3 per cent of the population over the age of 50 years and is increasingly common with age. The risk of progression to myeloma has been reported to be approximately 1 per cent per year over the following 25 years.

Although often an incidental finding on screening, the detection of a serum paraprotein understandably leads to concern. It is important to be aware that the risk of progression to myeloma varies widely and can be assessed based on the isotype (IgG, IgA, etc) of the paraprotein, its size and whether the serum-free light chain ratio is normal or not.

If SPEP detects an IgG paraprotein of less than 15g/L and if the serum free light chain kappa:lambda ratio is normal, these criteria identify a group of patients with low-risk disease, constituting almost 40 per cent of all MGUS patients, who only have a 5 per cent risk of progression to myeloma at 20 years. As a result, the MGUS guidelines of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology recommend that such patients be discharged from haematology clinics back to GPs for routine monitoring (https://www.b-s-h.org.uk/guidelines/).

Smouldering multiple myeloma (SMM) is an intermediate state between MGUS and myeloma. It is diagnosed when the plasma cells infiltrate within the bone marrow increases to greater than 10 per cent and/or the paraprotein increases to more than 30g/L in the continuing absence, however, of end-organ damage. The risk of progression to symptomatic myeloma is 10 per cent per year.

<h3><strong>Diagnosis of myeloma</strong></h3>

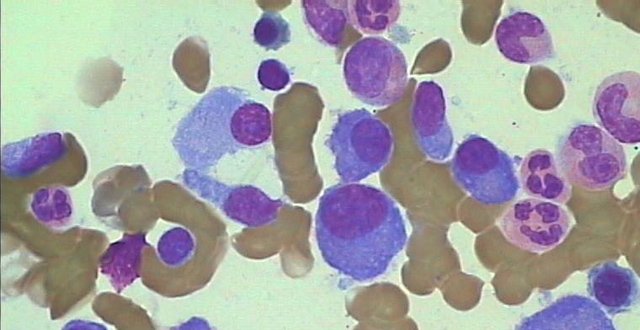

The diagnosis of symptomatic myeloma requires the presence of an infiltrate of malignant plasma cells (>10 per cent) in the bone marrow (see Figure 1), a monoclonal paraprotein in the serum and/or urine, and either the presence of end-organ damage as evidenced by the so-called CRAB criteria of hypercalcaemia (C), renal insufficiency (R), anaemia (A), and bone (B) lesions, or the presence of one of three biomarkers highly predictive of early progression to such end-organ damage: (1) greater than 60 per cent plasma cells within the bone marrow; (2) a highly skewed ratio of the involved to the uninvolved serum free light chain (>100:1), and; (3) more than one focal lesion greater than 5mm in diameter on MRI.

The commonest symptoms at presentation are fatigue and bone pain. Mid-to-low back pain has often been present for several months before cross-sectional imaging reveals damage, commonly vertebral fractures and co-existing asymptomatic lytic lesions. Occasionally, patients present with pathological fractures (Figure 2).

Be alert to an unexplained gap between the total protein (60-to-80g/L) and the serum albumin (35-to-50g/L) on the ‘liver profile’, as this may indicate the presence of a paraprotein and should prompt consideration of a request for a SPEP.

The following laboratory investigations should be performed in a patient suspected of having myeloma: FBC; renal profile; calcium level; and serum and urine protein electrophoresis. The serum free light chain assay is an expensive confirmatory assay and is usually ordered in the haematology clinic.

Except in rare cases of non-secretory MM, the identification and quantification of a monoclonal protein (M-protein) in the serum or urine is essential to the diagnosis and monitoring of myeloma. SPEP provides a measurement of the three principal immunoglobulins, IgG, IgA and IgM. If a monoclonal band or paraprotein is detected on the gel, immunofixation with antibodies to heavy chains (G, A, M) and light chains (kappa, lambda) is automatically performed to identify the paraprotein, eg, IgG kappa or IgA lambda.

The serum free light chain assay is a test using an antibody specific for free circulating immunoglobulin light chains. This test is reported as the ratio of kappa to lambda light chains. This test has improved our ability to diagnose and monitor light chain myeloma and has removed the need for sequential 24-hour assessments of urinary light chain excretion, a difficult test to perform in an older, frailer population and one that is often incomplete.

A urine collection should still be performed at diagnosis to assess for nephrotic syndrome. The spot protein to creatinine ratio (PCR) may be used as a surrogate for a 24-hour urinary protein in patients with newly-diagnosed myeloma. It is important to be aware that the standard urinalysis reagent strips do not detect light chains. If there is a discrepancy between such a urine dipstick test for protein and a separate test for urinary protein excretion, this raises the possibility of light chain proteinuria.

Until recently, a skeletal survey comprised of plain x-rays of the skull, trunk and limbs was the principal imaging modality used to assess for myeloma-related bone disease. However, this is a relatively insensitive technique and guidelines from the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) in 2017 recommended either whole-body, low-dose CT, whole-body MRI or, occasionally, PET/CT as the imaging techniques of choice.

<h3><strong>Prognosis</strong></h3>

The encouraging improvements in survival rates mask the fact that myeloma, though always a clonal malignancy of plasma cells, is a disease characterised by marked clinical and biological variability. Host factors such as age or frailty, the disease burden and tumour biology all combine to determine overall survival in any given patient. The Revised International Staging System (R-ISS) incorporates serum albumin, beta-2 microglobulin, LDH and FISH cytogenetic results as markers in a robust prognostic tool for newly-diagnosed patients.

FISH is a genetic test consisting of the use of labelled probes on plasma cells from a bone marrow aspirate to assess for the presence of specific known chromosomal abnormalities, principally hyperdiploidy, a good prognostic marker, and translocations involving the immunoglobulin-heavy chain enhancer at 14q, generally conferring a worse prognosis, eg, t(4;14), t(14;16) or t(14;20). FISH results are used to stratify patients in clinical trials and can also usefully inform treatment decisions in routine clinical practice.

<h3><strong>Treatment</strong></h3>

There are several phases to treatment: Induction chemotherapy following diagnosis; ASCT for younger, fitter ‘transplant-eligible’ patients; maintenance treatment until disease progression; and treatment at relapse.

Bortezomib is a first-in-class proteasome inhibitor, which has been available for use in Ireland since 2004. The main complications are transient gastrointestinal upset and peripheral neuropathy. This latter complication has been found to be less common when it is administered subcutaneously rather than intravenously and on a once-weekly rather than a twice-weekly schedule.

Immunomodulatory drugs are derived from the parent compound, thalidomide, which tragically led to an epidemic of foreshortened limbs (phocomelia) when it was used as treatment for ‘morning sickness’ in the first trimester of pregnancy in the 1950s in Europe. In 1999, thalidomide was found to be effective in the treatment of relapsed myeloma and prompted the development of the more potent, less-toxic compounds, lenalidomide and pomalidomide. As they are teratogenic, strict prescribing guidelines are in place to avoid inadvertent foetal exposure.

Modern induction chemotherapy usually consists of a ‘triplet regimen’ incorporating a proteasome inhibitor, usually bortezomib, or an immunomodulatory drug, usually thalidomide or lenalidomide, in combination with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide. The woman in the case report described in this article received cyclophosphamide, bortezomib and dexamethasone (CyBorD). Alternatives would include lenalidomide, bortezomib and dexamethasone (RVD) or bortezomib, thalidomide and dexamethasone (VTD). Most patients will respond to any of these regimens. A notable change over the last decade has been the use of lower doses of dexamethasone, usually now given in weekly pulses rather than in longer four-day blocks.

<h3><strong>Transplant-ineligible patients</strong></h3>

As the median age at diagnosis of myeloma is around 70 years, many newly-diagnosed patients are frail and have multiple coexisting illnesses. Dose-reduced triplet regimens or orally-administered doublets, such as lenalidomide and dexamethasone, are likely to be better tolerated in this population. In the absence of transplantation, longer courses of less intensive treatment are often an effective, less toxic approach.

<h3><strong>Transplantation</strong></h3>

ASCT remains the standard-of-care for the treatment of younger, fitter patients. In a large MRC UK randomised controlled trial, those in the transplant arm survived, on average, one year longer. The upper age limit is based upon biological rather than chronological age although, for practical purposes, it is approximately 70 years. The transplant admission lasts for three weeks and the main complications are myelosuppression and mucositis.

At St James’s Hospital, Dublin, 557 patients underwent ASCT for myeloma between 1999 and 2016, 503 ‘up-front’ shortly after diagnosis and 54 as a second transplant, usually several years later (see Figure 3). The population consisted of 306 (60.8 per cent) men and 197 (39.2 per cent) women. The median ages at transplant were: 53 (35-to-67) years (I), 57 (31-to-69) years (II) and 59 (29-to-70) years (III), respectively.

During this period, novel drug classes have included proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib, carfilzomib (Named Patient Programme (NPP)) (2016-2017)), immunomodulatory drugs (thalidomide, lenalidomide and pomalidomide) and, more recently, monoclonal antibodies (daratumumab (NPP) (2016-2017)). These developments have led to consistently improving five-year overall survival rates in younger transplant-eligible patients in these three consecutive six-year cohorts, as follows: 62 per cent (I), 67 per cent (II) and 80 per cent (III), respectively (see Figure 4).

<h3><strong>Maintenance </strong></h3>

Maintenance treatment consists of the continued use of a therapy until disease progression. Two large, randomised, controlled trials evaluated the efficacy of maintenance low-dose lenalidomide in the post-transplant setting. A recent meta-analysis reported improved overall survival at seven years of follow-up in those patients who received maintenance.

<h3><strong>New developments </strong></h3>

There have been two main advances in the treatment of myeloma in the last three years. The first has been the development of several antibodies targeting proteins on the plasma cell surface. Daratumumab is a humanised IgG1κ monoclonal antibody against CD38, which has shown promising single-agent activity in relapsed and refractory myeloma. It is available for use in Ireland from April 2018. Other novel antibodies include isatuximab, also targeting CD38, and elotuzumab, targeting the protein SLAMF7.

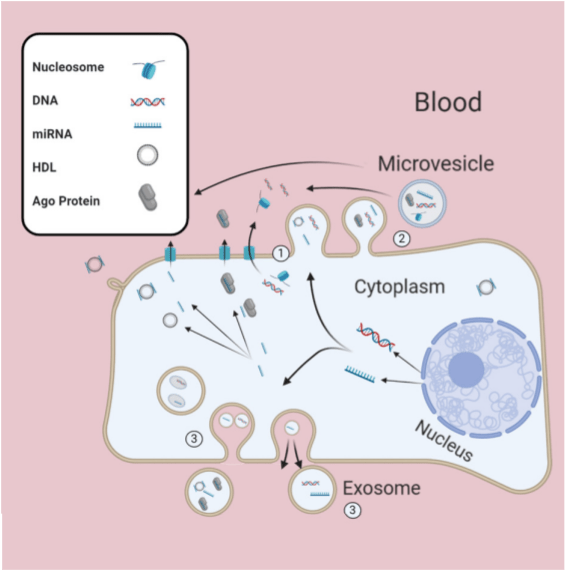

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is a revolutionary new approach to the treatment of haematological malignancies, including myeloma.

This technique involves the collection of peripheral blood lymphocytes from patients by apheresis. These are then genetically engineered <em>in vitro</em> to target cell surface proteins expressed by a given cancer cell and re-infused back into the patient following immunosuppressive treatment.

The most promising results so far in myeloma have been based on CAR-T cells targeting the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), a protein whose expression is largely restricted to plasma cells. High response rates have been reported in heavily pre-treated patients who had become refractory to all other treatment options. These are, however, early days and although highly promising, challenges include toxicity, cost and patient selection. Clinicians are working with the pharmaceutical industry to bring CAR-T cell clinical trials to Ireland over the coming year.

In summary, the last 20 years have seen a complete transformation of the field of myeloma therapies, which has resulted in deeper remissions and greatly improved survival rates (see Figure 5). Although currently incurable, the range of available therapies and the prospect of CAR-T cell approaches raise the possibility that we may achieve cures in some patients in the coming years.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.