Dr Iona Galloway, Dr Colleen Flannery and Prof Amar Agha outline the latest treatment approaches to differentiated thyroid cancer, which accounts for over 90 per cent of all thyroid cancers with a female predominance

Case report

A 40-year-old female presented to her GP with a palpable, painless, right-sided neck lump, which had been present for six months.

Thyroid function tests were normal. A neck ultrasound was performed, which demonstrated a 2.5×2.3cm solid hypoechoic thyroid nodule with irregular margins and microcalcification (highly suspicious, U5 classification) but no abnormal lymph nodes. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology was diagnostic of papillary thyroid cancer (Thy 5 classification).

The patient underwent a thyroid lobectomy; histology revealed an intrathyroidal classic variant papillary cancer.

Subsequent follow-up showed normal thyroid function, stable serum thyroglobulin levels and normal-looking contralateral thyroid lobe.

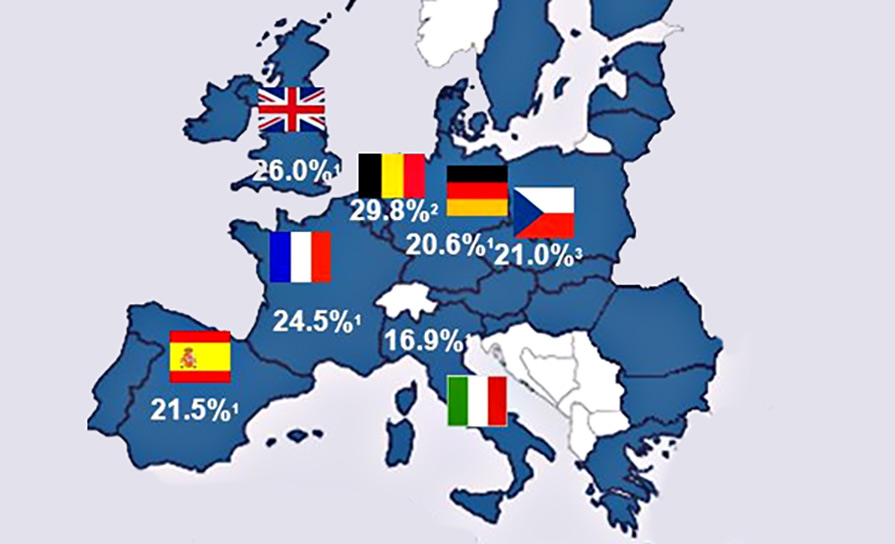

Differentiated thyroid cancer (papillary and follicular) accounts for over 90 per cent of all thyroid cancers with a female predominance. There has been a sharp increase in the rate of this diagnosis over the last four decades in many developed countries, with 2009 US data showing an incidence of 14.3 per 100,000 of the population and rising. Unpublished Irish data shows an almost 400 per cent increase in diagnosis between 1996 and 2012. By 2019, thyroid cancer is estimated to be the third-most commonly diagnosed cancer in women in the US. While the reason for this increase is not entirely clear, it is widely believed to be due to widespread use of neck ultrasound and other imaging modalities. The most established risk factor for differentiated thyroid cancer is exposure to ionising radiation, particularly in childhood. About 5 per cent of cases are familial.

Thyroid cancer usually presents as a palpable neck lump or as an incidental finding of a nodule on imaging. Neck ultrasound can be useful in the risk stratification of thyroid nodules and selection of nodules requiring an FNA. Different thyroid and radiology scientific bodies have introduced a reporting system. One of them is shown in Table 1. FNA cytology is the method of choice in differentiating benign from suspicious/malignant nodules, although there is a non-diagnostic rate of 15-to-20 per cent. Concerns have been raised about false-negative results with thyroid FNA; however, our data and that of others showed that when a well-targeted biopsy is taken with expert thyroid cytology review and multidisciplinary discussion, the false negative rates are very low (<1 per cent).

Management

The TNM staging of thyroid cancer is shown in Table 2.

Surgery

Microcarcinoma (<1cm)

Traditionally, intrathyroidal microcarcinomas were treated with thyroid lobectomy. However, recent evidence suggests that active surveillance of these small cancers may be acceptable, as only a small minority will progress over time.

Macrocarcinomas (>1cm)

Low-risk cancers between 1-to-4cm in maximum diameter without extrathyroidal extension and without clinical evidence of lymph node or distant metastases can be managed with either a lobectomy or a total thyroidectomy. Data suggests there is no difference in mortality between the two procedures, although it remains unclear whether total thyroidectomy confers a lower risk of recurrence.

For other cancers, total thyroidectomy is recommended. Thyroidectomies should be undertaken by a high-volume thyroid surgeon. Complications include recurrent laryngeal nerve damage and hypoparathyroidism in a minority of cases.

Radioactive iodine (RAI) ablation/therapy

The use of RAI ablation/therapy in the postoperative thyroid cancer patient has evolved over time. Historically, almost all patients who had a total thyroidectomy were treated with high-dose RAI to ablate any remaining normal thyroid remnant and also any microscopic lymph node metastases. Modern guidelines, however, do not recommend its use in low-risk patients (tumour less than 4cm without gross extrathyroidal extension and no lymph node metastases). On the other hand, RAI is recommended in high-risk patients (gross extrathyroidal extension, persistent or metastatic disease). For those in between, RAI may be considered on a case-by-case basis, especially in those over the age of 55 years or those with large-volume lymph node involvement.

TSH suppression

Similar to RAI treatment, thyroxine therapy to suppress (usually to undetectable levels) TSH is indicated for patients at high risk or those with persistent or metastatic disease.

Other novel treatments

A small percentage of patients will show disease progression, despite conventional treatments outlined above. The angiogenesis inhibitors lenvatinib and sorafenib have shown improved progression-free survival in patients with locally-advanced or metastatic disease that is resistant to RAI therapy. There also appears to be a higher overall survival with those agents, but the extent is not clear.

Follow-up

Patients with thyroid cancer should be followed-up in regional thyroid cancer centres with access to a multidisciplinary team. Patients are usually seen every six-to-12 months with measurement of thyroid function (TSH), thyroglobulin and periodic neck ultrasound or other imaging modalities as indicated. Thyroglobulin is a very sensitive marker of benign or malignant thyroid tissue. Therefore, in patients who underwent a total thyroidectomy and radioiodine ablation (athyreotic patient), a suppressed stimulated thyroglobulin together with a normal neck ultrasound are highly suggestive of disease remission.

Prognosis

With appropriate treatment, differentiated thyroid cancer has an overall excellent prognosis. The overall survival is greater than 90 per cent at 10 years. Those with stage 1 have almost a 100 per cent 10-year survival; stage 2, 95-95 per cent; stage 3, 60-70 per cent; and those with stage 4, <50 per cent 10-year survival.

References on request

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.