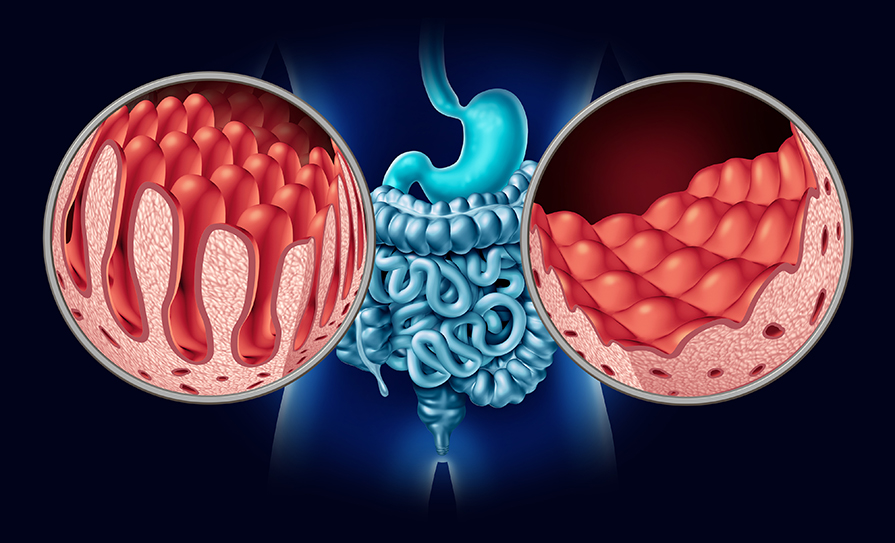

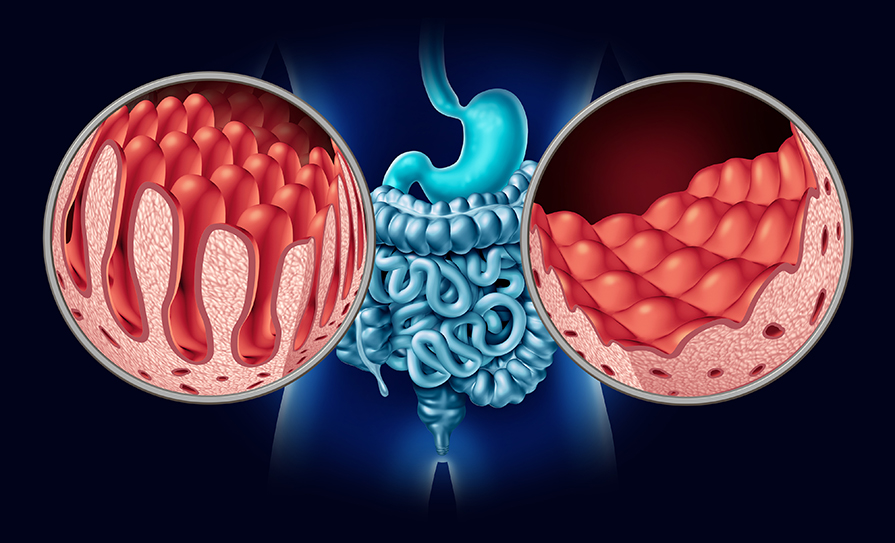

The impact of non-adherence to a gluten-free diet can have wide-ranging effects on our patients

I want you to consider that everything we’re doing is wrong.” This was the opening statement made by a Professor of Gastroenterology presenting at a UK symposium last year. The topic of discussion was how we monitor coeliac disease after initial diagnosis. With adherence rates reported to be between 42-and-92 per cent, it is true that many coeliacs are at risk of developing complications such as lymphoma, ulcerative jejunitis, osteoporosis, infertility, and nutritional deficiencies.

In children signs of non-adherence include faltering growth and delayed puberty. To reduce the incidence of comorbidity we must have the right tools to detect gluten exposure. There are a variety of methods used in practice to assess adherence to a gluten-free diet – validated scores, questionnaires, ask the patient, request a dietitian review, and serology. Biomarker and score results give us quick reassurance; until they don’t.

Long-term follow-up in coeliac disease remains controversial. Currently, there are no effective non-invasive markers of gluten-free diet adherence, with point-of-care testing, dietary adherence questionnaires, and serology all having poor sensitivity for the detection of villous atrophy (VA). Despite this information being disseminated in the literature and at conferences, serological response continues to be used as a surrogate for histological recovery. A recent survey reported 65 per cent of gastroenterologists in Canada used bloods including serology as a monitoring tool. The details suggest serology was performed less frequently in adults than children, in favour of routine intestinal biopsy, showing a trend towards the use of the gold standard assessment.

There are inherent difficulties in using coeliac serology as a monitoring tool. In order to obtain clinically-meaningful endpoints, it is essential that patients are eating a certain amount of gluten prior to testing. Guidelines vary on the amounts and duration with one institution saying gluten in more than one meal daily for six weeks, and another recommending one-to-three slices of bread daily for one-to-three months before testing. Once you can be sure the patient is adequately prepared for a test there are a few other serological anomalies to consider. It is reported that 1.7-to-5 per cent of coeliacs are affected by seronegative coeliac disease (SNCD). This is a rare and still poorly defined form of coeliac disease, presenting with negative serology, villous atrophy, genetic compatibility, with or without symptoms of malabsorption and who demonstrate clinical and histological response to a gluten free diet. A further 2 per cent of coeliacs have IgA deficiency. This is a separate entity to seronegativity. In this case, if not done automatically by the lab, you need to order IgG antibodies as an alternative to IgA antibodies. According to a recent meta-analysis, sensitivity of the anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTg) antibody for ongoing villous atrophy was only 43.6 per cent. So even if well considered and accurately prepared there appears to be a limit to how much serological testing can tell us about mucosal healing. It is like flipping a coin. There is a 50 per cent chance of persistent villous atrophy with a negative IgA tTg result.

If you decide to pursue biopsy as a method of monitoring and find persistent villous atrophy, there are caveats here too. There are many mimics of villous atrophy including use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or olmesartan, helicobacter pylori gastritis, giardiasis, collagenous or microcytic colitis to name but a few. The timing of a biopsy must also be selected carefully. Villous atrophy improves on a strict gluten-free diet, but this may take two-to-three years so be careful not to repeat the biopsy too early.

It has been suggested that immune tolerance is possible over time. A recent study showed that neither occasional nor voluntary dietary gluten intake was associated with the onset of clinical, serological, histologic, or endoscopic changes in a group of coeliac patients. Interestingly, no association was found between histological alterations and the amount of gluten intake following diagnosis. This means the traditional advice of a strict gluten-free diet for all warrants further investigation and review. The tolerable amount of gluten is still contended, and this casts a shadow over current dietary advice. Perhaps there is a subset of patients where a more relaxed approach can be considered, but we need the monitoring tools to allow that to happen in a safe way.

Dietetic assessment of adherence also has limitations. Targeted dietetic intervention through removal of identified gluten sources or avoidance of trace amounts of gluten led to resolution of persistent villous atrophy in only 50 per cent of patients studied.

Coeliac serology appears to be a poor surrogate marker for mucosal recovery, and dietary assessment may fail to uncover a potential gluten source in some patients with ongoing villous atrophy. This could be explained by non-disclosure or under reporting of dietary intake, but warrants further investigation. Although current clinical guidelines do not recommend routine repeat biopsy, it appears to be the surest way to monitor mucosal healing and response. Although such a change in clinical practice would have financial implications, the cost of non-adherence has a clear impact on the health of individuals. Equally, an overly strict gluten-free diet can affect quality-of-life. In the meantime, we need more accurate non-invasive markers of mucosal damage in children and adults with coeliac disease who are following a gluten-free diet. Perhaps novel biomarkers such as gluten immunogenic peptide (GIP) might have the ability to increase detection rates of non-adherence. This convenient urine test checks for gluten exposure. There has been criticism of false negatives, but researchers say testing over several days is a pragmatic approach. According to one study, three negative urine tests from three different days revealed a 97 per cent possibility of no villous atrophy. New biomarkers are promising and will add to our understanding of gluten metabolism and, with additional studies, could be used as a supplemental tool in the future management of our patients.

The spectrum of gluten-related disorders (GRDs) includes dermatitis herpetiformis, gluten ataxia, wheat intolerance and non-coeliac gluten sensitivity. Greater awareness of testing guidelines is important to both diagnose and effectively manage GRDs lifelong.

UK National Institute for Clinical Care and Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend that serological testing for coeliac disease should be considered in people with unexplained neurological symptoms, particularly peripheral neuropathy or ataxia, specifically anti gliadin antibodies (AGA). According to the gluten sensitivity neurology service at Sheffield University, UK, these disorders account for 26 per cent of all neuropathies. A new cut-off point for AGA has been set to diagnose neurological dysfunction such as gluten ataxia (GA). GA is the second highest cause of ataxia in the UK; 40 per cent of these have villous atrophy. The significance of abnormal AGA outside of enteropathy in untreated GA, however, is the prevention of cerebellum atrophy. A gluten-free diet normalises AGA if detected early. It also improves spectroscopy imaging. In the case of late diagnosis, the diet can only stabilise GA. Unfortunately, this tends to be the case in the absence of gastrointestinal symptoms and average time to diagnosis is 10 years resulting in permanent neurological damage. Ask a patient to stand on one foot and walk heel to toe to assess gait. To further increase detection rates, healthcare practitioners should be alert to reports of intractable headaches and balance problems. Patients usually do not report these to their gastroenterologist because they are focused on bowel issues, but these may have been reported to a GP or other healthcare professional. Coeliac disease also increases the risk of vascular dementia.

In conclusion, the impact of non-adherence to a gluten-free diet can have wide-ranging effects on our patients, from chronic micronutrient deficiencies to infertility. Current monitoring methods fall short in detecting rates of non-adherence in coeliac disease, leading to comorbidities that are largely preventable. Long-term monitoring is not as straightforward as we once thought and requires more thorough consultation. Do not rely on serology alone. Serology, dietary adherence, and mucosal remission do not have a perfect relationship. The only way to know for sure if your patient is responding to diet therapy is to repeat biopsy. GRDs are lifelong chronic conditions. Patients require a long-term monitoring plan at time of diagnosis with access to appropriate services and healthcare professionals including a registered dietitian. Despite the high prevalence of coeliac disease in Ireland, there are currently no dedicated community or primary care services to co-ordinate the necessary follow-up. Care is managed by gastroenterology outpatient departments and GPs around the country. To reiterate the opening statement, please consider everything we are doing is wrong.

References

Schiepatti A, Savioli J, Vernero M, Borrelli de Andreis F, Perfetti L, Meriggi A, Biagi F. Pitfalls in the diagnosis of coeliac disease and gluten-related disorders. Nutrients. 2020 Jun 7;12(6):1711. doi: 10.3390/nu12061711

Rej A, Aziz I, Sanders DS. Coeliac disease and non-coeliac wheat or gluten sensitivity. J Intern Med 2020;288:537-4

Sharkey LM, Corbett G, Currie E, Lee J, Sweeney N, Woodward JM. Optimising delivery of care in coeliac disease – comparison of the benefits of repeat biopsy and serological follow-up. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013 Nov;38(10):1278-91. doi: 10.1111/apt.12510

Silvester JA, Rashid M. Long-term management of patients with coeliac disease: Current practices of gastroenterologists in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010 Aug;24(8):499-509. doi: 10.1155/2010/140289

Elli L, Bascuñán K, di Lernia L, Bardella MT, Doneda L, Soldati L, et al. Safety of occasional ingestion of gluten in patients with coeliac disease: A real-life study. BMC Med. 2020 Mar 16;18(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-1511-6

Ludvigsson JF, Bai JC, Biagi F, Card TR, Ciacci C, Ciclitira PJ, MM, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology. Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: Guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 2014 Aug;63(8):1210-28. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306578

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.