Dr Anne Marie Hannon gives a detailed overview of the characteristics of acromegaly

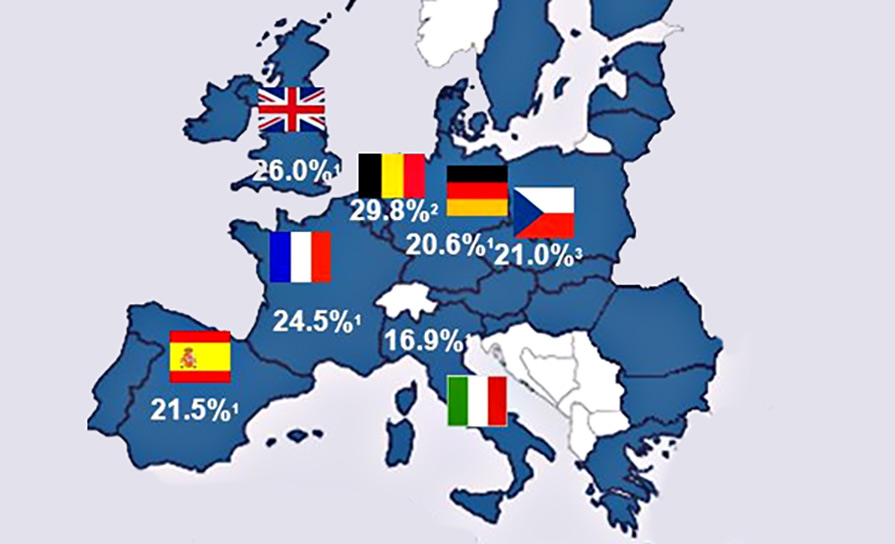

Acromegaly is a chronic, systemic condition characterised by growth hormone (GH) excess, typically secreted by a pituitary adenoma. Acromegaly is a rare disease and it is under diagnosed. The prevalence of acromegaly has been estimated from several registry-based studies. The prevalence ranges between 20 cases per million in the Mexican acromegaly registry to 134 cases per million in the Icelandic registry. The remainder of European registries estimate the prevalence to be 40-80 cases per million population. Acromegaly affects both men and women equally and the average age at diagnosis is 40 to 50 years.

Untreated acromegaly is associated with increased mortality in comparison to the background population. Mortality is traditionally due to cardiovascular disease, but some series have also shown an increased risk of malignancy. The Endocrine Society recommends treating to target a normal plasma IGF-1 concentration for age and a GH concentration of <1ng/ml. Population studies have shown that if the plasma GH and IGF-1 are controlled to this target, then the standardised mortality ratio (SMR) returns to that of the background population.

The onset of acromegaly is typically insidious in nature; therefore, the diagnosis is often delayed. It has been reported that patients have the disease an average of eight-to-10 years prior to diagnosis. During this time excessive GH and IGF-1 concentrations can lead to significant morbidity. As acromegaly is a multi-system disease, patients with acromegaly may present to a wide range of specialties. Approximately 40 per cent of acromegaly cases are diagnosed incidentally (by unrelated physical or dental examination). The remainder may be diagnosed when they present to ophthalmologists with visual disturbance, by rheumatologists with severe osteo-arthritis, by gynaecologists when they present with menstrual disturbance and by sleep physicians with obstructive sleep apnoea. As these conditions are extremely common in the background population it would not be cost-effective to screen all these patients for acromegaly. Therefore, a high clinical index of suspicion is required to accurately identify patients who should be screened for acromegaly.

Clinical presentation

Acromegaly patients may present due to symptoms and signs of GH excess, systemic complications of the disease or due to compression effects of an expanding pituitary mass. Clinical manifestations of acromegaly range from subtle facial features to marked clinical signs. In a large published case series only 10-15 per cent of acromegaly patients actively sought medical attention for a perceived change in appearance. More often, patients present incidentally or with complications of the disease.

Symptoms

Symptoms of acromegaly include sweating, arthralgia, headaches, menstrual disturbances/erectile dysfunction and symptoms of respiratory or cardiac compromise. Patients may also present with visual compromise if the pituitary adenoma extends superiorly into the suprasellar cistern and compresses the optic chiasm. Persistent compression may result in blindness if left untreated.

The majority of patients with acromegaly have macro-adenomas; therefore symptoms of hypopituitarism may be present. Hyperprolactinaemia occurs in approximately one third of patients with acromegaly, this may be due to compression of the pituitary stalk by a large adenoma or co-secretion of prolactin and GH from the adenoma. Acromegaly should therefore be considered as a rare, but important cause of hyperprolactinaemia.

Signs

The classic acromegaly phenotype includes enlarged hands and feet, prognathism, prominent supra-orbital ridges, increased interdental space, dental malocclusion and macroglossia. Excessive growth of hands and feet is present in the vast majority of patients with acromegaly in published case series. This occurs predominantly due to soft tissue swelling, which increases the width of the feet and fingers leading to larger ring and shoe sizes.

Up to 70 per cent of patients with acromegaly have hyperhidrosis and oily skin. Signs of insulin resistance may also be present including acanthosis nigricans and skin tags.

Complications

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA)

Macroglossia, prognathism and hypertrophy of the laryngeal mucosa all contribute to upper airway obstruction in acromegaly. Sleep apnoea has been reported to occur in between 20-to-87 per cent of patients in the literature. The discrepancy of rates observed likely reflects varying practices in screening for OSA in acromegaly. Normalisation of plasma GH and IGF-1 concentrations typically results in improvement and in some cases resolution of OSA.

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Peripheral neuropathies are reasonably common at presentation in acromegaly. They occur due to neural enlargement and increased tissue swelling. Carpal tunnel syndrome is the most common peripheral neuropathy observed, and it has been reported in 20-64 per cent of patients at diagnosis. As the symptoms generally improve, or disappear with the successful treatment of acromegaly, there is usually no indication for surgical intervention for carpal tunnel syndrome unless the symptoms persist post normalisation of plasma GH and IGF1.

Metabolic complications

GH excess is associated with insulin resistance, increased gluconeogenesis and lipolysis, all of which contribute to the development of impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) or diabetes mellitus. The reported prevalence of IGT varies widely in the literature, with figures of up to 40-52 per cent in some series. Diabetes mellitus is present in up to 28-42 per cent of acromegaly patients at diagnosis. Again, successful treatment of elevated GH and IGF-1 concentrations will result in remission or improvement of glycaemic control.

Cardiomyopathy

GH and IGF-1 excess may induce a specific acromegalic cardiomyopathy which is characterised by concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricle, diastolic dysfunction and progressive systolic impairment which may ultimately lead to heart failure. The reported prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) in studies varies widely between study populations, with reported prevalence ranging between 11-and-78 per cent. The wide variation in reported prevalence of LVH on echocardiogram testing is likely due to different study designs, different criteria for diagnosing LVH and different study populations. Successful treatment of acromegaly with both surgery and medical therapy has been shown to reduce the prevalence of LVH in patients with acromegaly. Diastolic dysfunction and myocardial fibrosis are also observed in acromegaly. Diastolic dysfunction has been shown to improve in patients with inactive disease compared to those with active disease. Valvulopathies (particularly aortic or mitral regurgitation), arrhythmias, and conduction disorders may also occur in acromegaly. Heart failure at diagnosis appears to a poor prognostic indicator, in one study, the one- and five-year mortality rates for patients with heart failure were 25 per cent and 37.5 per cent, respectively.

Hypertension

The reported prevalence of hypertension in acromegaly studies ranges from 18-60 per cent with a mean prevalence of 35 per cent. Most studies are retrospective in nature and blood pressure is measured at clinic visits. A minority of studies have evaluated blood pressure using 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitors (ABPM). Hypertension in acromegaly is predominantly diastolic hypertension, occurs earlier, and is less commonly associated with a family history of hypertension than the general population.

Osteo-arthritis

Arthropathy is extremely common in acromegaly, and has been reported to be present in up to 84 per cent of patients at diagnosis. It is more common in older patients and it may affect any joint(s). The majority of patients exhibit joint swelling and cartilaginous thickening. Acromegaly also appears to be associated with increased risk of vertebral fractures, in spite of normal bone mineral density. Whilst arthralgia often improves with the reduction in plasma GH and IGF-1 concentration, the damage due to bone remodelling and osteophyte formation is usually permanent and may negatively impact the quality-of-life for many patients living with acromegaly.

Who to screen?

As acromegaly is a rare disease, identifying which patients to screen can be challenging. Screening is recommended for patients presenting with a new pituitary tumour, systemic effects of GH/IGF-1 excess, cardiovascular and metabolic features, respiratory and bone/joint manifestations as described above. In particular, screening should be considered in patients with medical conditions such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, carpal tunnel syndrome, severe osteo-arthritis, hypertension and OSA. A number of studies have looked at screening populations with diabetes mellitus, carpal tunnel syndrome and sleep apnoea. Due to the low prevalence of acromegaly however, universal screening in these conditions does not appear useful. Instead a clinical assessment with an evaluation of acromegaly symptoms and signs will guide which patients to screen. 3D facial analysis has also been shown in some studies to be effective at early identification of patients with acromegaly, however, if and how this could be used clinically to identify patients with the disease remains to be seen.

Diagnosing acromegaly

Screening tests for acromegaly are a plasma IGF-1 concentration +/- plasma GH. Plasma GH concentrations may be misleading, as GH is secreted in a pulsatile manner. If the plasma IGF-1 concentration is elevated or equivocal, patients should be referred to a specialist centre for further investigation. Severe obesity, prolonged fasting and severe malnutrition suppress plasma IGF-1 concentrations in patients without acromegaly, but may also affect concentrations in patients with acromegaly. Extreme stress, physical exercise, acute critical illness and fasting state may cause a physiological increase in the peak GH secretion. Therefore, if there is a high index of suspicion, consider repeating the test. Diagnosis during pregnancy is particularly challenging, as there is significant homology between placental GH and 22kDa pituitary GH and some GH assays will cross-react with placental GH.

Confirmation of the diagnosis is made with failure to suppress GH concentrations following a 75g glucose load. A normal response is defined as suppression of the plasma GH to <0.4ng/ml following a glucose load. After GH excess has been demonstrated, the next step is identifying the source of GH hypersecretion. Pituitary MRI is recommended, given >95 per cent of acromegaly cases are caused by a pituitary adenoma.

More recently, a new entity termed ‘micromegaly’ has been described. This describes a group of patients with raised IGF-1 concentrations and apparently normal basal and/or glucose suppressed GH concentrations at diagnosis. These patients more commonly have microadenomas and lower plasma IGF-1 concentrations in comparison to the classic acromegaly patients. Micromegaly patients therefore appear to have distinct features to the typical acromegaly patient and the clinical implications of this condition require further study, to evaluate if a mildly elevated IGF-1 in the setting of a controlled GH is harmful to the patient.

Despite significant advances in therapeutic options for patients with acromegaly over the past number of decades, early identification remains challenging. An enhanced awareness of the signs and symptoms among medical professionals is of paramount importance in the prompt diagnosis of acromegaly, initiation of appropriate treatment and ultimately in providing improved patient care.

References on request

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.