Different enterovirus strains can cause more severe disease with varying skin findings compared with so-called typical viral strains of hand, foot, and mouth disease.

Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) is a viral illness that mainly affects children younger than five years of age. In the past it was caused mostly by coxsackievirus A16 and enterovirus 71 (E71), and characterised by small blisters of the oral mucosa, palms, and soles, lasting for seven-to-10 days. Recently, different enterovirus strains such as coxsackievirus 6 (CV6) have become a major cause of HFMD outbreaks in Ireland and worldwide. These strains cause more severe disease with varying skin findings compared with so-called typical viral strains (CV A16 and E71). We present examples of the skin findings of HFMD associated with these newer circulating strains to update and empower primary care healthcare professionals.

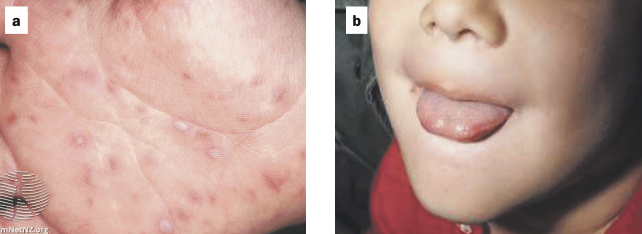

Figure 1: (a) Palmar vesicles and b) Small aphthae like vesicles on the tip of the tongue in a patient with ‘traditional’ HFMD. Image courtesy of Dermnet7

HFMD: An overview

HFMD is a common childhood illness that is usually self-limiting and caused by a group of viruses known as enteroviruses. It most commonly affects those under the age of five years and can cause constitutional upset with pyrexia associated with a mucocutaneous eruption and sore throat (herpangina). Historically, triggered by coxsackievirus A16 and enterovirus 71, it was easily identified by clusters of small vesicles (clear fluid filled blisters), often shaped like rugby balls, with a grey hue usually less than 5mm in size on the palms of the hands, soles of feet, and within the oral cavity (Figure 1). Current nomenclature and most online literature reflects this.1,2 We illustrate the additional skin findings that may accompany the more recent circulating viral strains to aid diagnosis and management.

Transmission is usually via droplet and faecal oral route. Incubation period varies, but is usually between three-to-five days, and children can transmit HFMD in their faeces for some time afterward. This age group are often in childcare settings where the illness can easily spread. Some exposed children can have little, or no symptoms, yet transmit the virus, thus recognition of cases is important to prevent outbreaks.

Children with HFMD are typically managed at home with general supportive measures including soft food, fluids, and paracetamol for fever and herpangina. They rarely require hospital admission unless they are unable to take sufficient fluids due to the ulcers in the oral cavity, or are unwell in another way, eg, persistent high temperature.

A very small number of children can develop neurological complications from enteroviruses, therefore, any child displaying extreme irritability or altered level of consciousness should present for assessment.

Some patients are sent to hospital due to the appearance of their skin despite being otherwise well, so in addition to preventing spread, it is useful to know what HFMD due to the newer strains can look like to better manage people in the community.

A subset of younger children can develop

a significant erosive napkin dermatitis, which can be painful and challenging to treat

Atypical HFMD

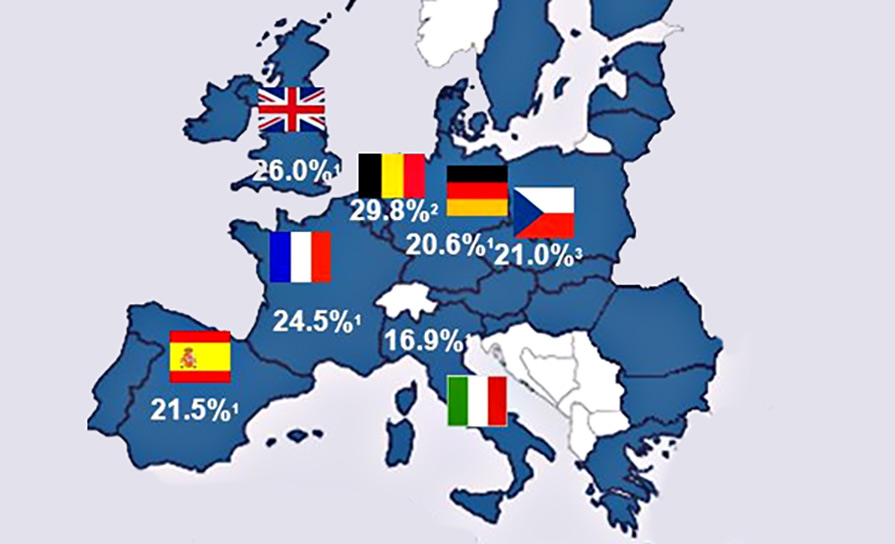

In 2012 an increase was noted in Irish hospital admissions3,4 of children who tested positive for the enterovirus and negative for herpes simplex virus (cold sore virus) and varicella zoster virus (chicken pox virus), with skin findings that differed from the classical HFMD described above and illustrated in Figure 1. This coincided with an emerging trend, first noted in South-East Asia, followed by the US, UK, and Ireland, implicating the coxsackie A6 viral strain in what was referred to as ‘atypical HFMD’.5,6

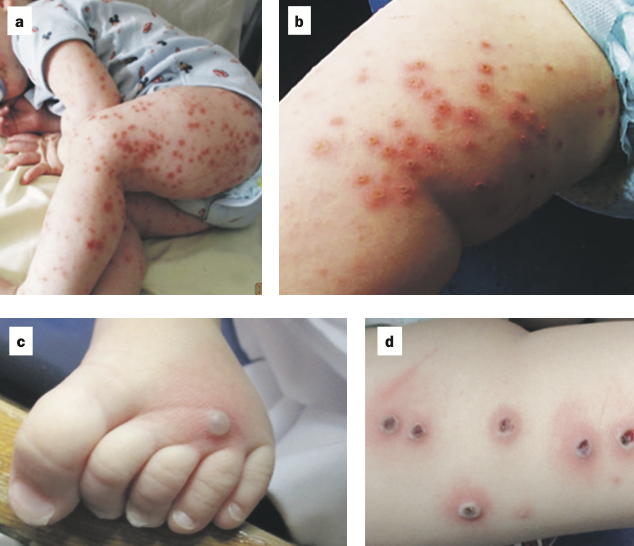

(d) Eroded bullous lesions on the thigh of the same child, some have developed an eschar. They occur on normal-appearing skin

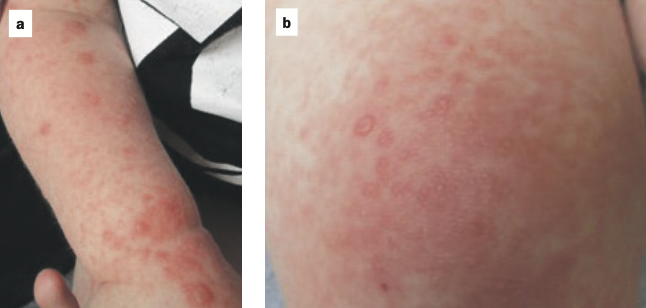

Compared to what was seen in the past, this strain affected both children and adults, and often had a more exuberant rash, with a higher temperature, and lasted for longer. The rash seen in atypical HFMD is often more extensive (Figure 2). Larger blisters are frequently seen and these bullae are described by some as ‘varicelliform’ (looking like chicken pox) (Figure 2 a-b). It frequently localises on dorsal rather than the palmar surfaces of hands and feet and often has a prominent perioral cutaneous eruption (stomatitis) (Figures 2, 3, and 6) rather than intraoral. The rash seen on the surface of the cheeks often resembles impetigo and indeed can be superinfected with Staphylococcus aureus, but is often accompanied by a similar rash in the perianal area and a generalised rash described below.

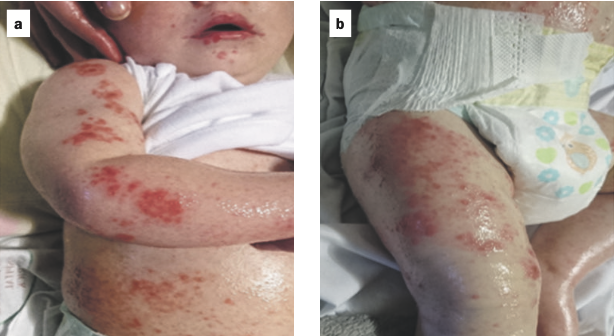

A subset of younger children can develop a significant erosive napkin dermatitis, which can be painful and challenging to treat. Other children with pre-existing atopic dermatitis can develop widespread vesicular eruptions coalescing in patches of eczema that looks like eczema herpeticum and is referred to, by some, as ‘eczema coxsackium’ (Figure 3).

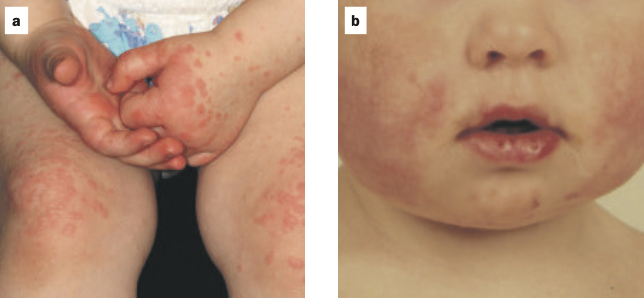

A more papular (bumpy) rash can occur, which looks like infantile acral papular acrodermatitis of childhood (also called Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, see Figure 4). This is a characteristic response of the skin to viral infection. It consists of a profuse symmetrical eruption of dull red spots that first develop on the thighs and buttocks, then on the outer aspects of the arms, and finally on the face (Figure 5). The individual spots are 5-10mm in diameter and are a deep red colour. Later they often look purple, especially on the legs. Some may develop clear vesicles.

Papular acrodermatitis of childhood is not usually itchy and the child may feel quite well or have a mild temperature despite the appearance of the rash. Mildly enlarged lymph nodes in the armpits and groins may persist for months. It settles without intervention but can take weeks to fade fully. Emollients are the treatment of choice. This may accompany the typical perioral and perianal papular vesicular eruption.

Shedding of the nail (onychomadesis) of an affected finger can occur in the aftermath. Nails and cutaneous lesions typically resolve without scarring.

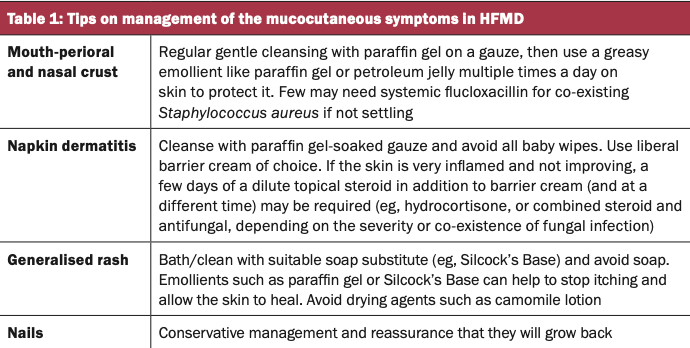

Treatment of HFMD is supportive (emollients, fluids, avoid irritants such as soaps and fragranced wipes), with use of antipyretics/analgesia as required. Enteroviruses do not typically respond to systemic acyclovir, but some patients with florid skin findings and systemic upset may receive this until their herpes and varicella swabs come back negative and their enterovirus positive. Other treatment tips are listed below in Table 1.

Conclusion

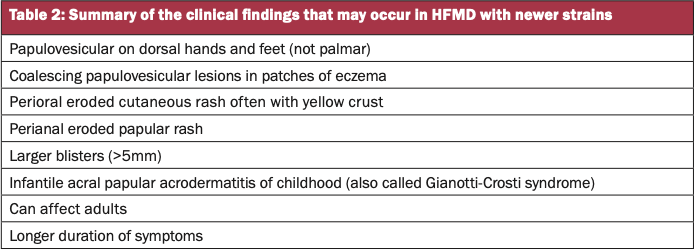

So called ‘atypical HFMD’ appears to be here to stay, yet parent, childcare, and indeed, healthcare information leaflets have not yet been updated to reflect the more variable florid cutaneous eruptions (summarised in Table 2). We believe there is merit in updating this literature to increase awareness of current presenting patterns. This may not only prevent some older children with more florid eruptions being admitted to an inpatient facility, but it will also allow those who look after younger children in the community to recognise the napkin dermatitis earlier, and may avoid widespread transmission.

References

1. National Health Service. Hand, foot, and mouth disease. UK: NHS; 2017. Available at: www.nhs.uk/conditions/hand-foot-mouth-disease/

2. Health Service Executive. Hand, foot, and mouth disease. Dublin: HSE; 2021. Available at: www2.hse.ie/conditions/hand-foot-mouth-disease/

3. Griffin L, Rafferty S, Ahmad K. Hand, foot, and mouth disease: Is it time for an update? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2023;48(11):1277-9

4. Molloy O, Flynn A, Azhar H, et al. Head, shoulders, knees, and toes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79 (Suppl.1):AB150

5. Sinclair C, Gaunt E, Simmonds P, et al. Atypical hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with coxsackievirus A6 infection, Edinburgh, United Kingdom, January to February 2014. Euro Surveill. 2014;19(12):20745

6. Lott JP, Liu K, Landry ML, et al. Atypical hand-foot-mouth disease associated with coxsackievirus A6 infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):736–41

7. DermNet [Internet]. Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease Images. [cited 2023 Dec 17]. Available at: www.dermnetnz.org/images/hand-foot-and-mouth-disease-images

8. DermNet [Internet]. Infantile papular acrodermatitis, Gianotti-Crosti images. [cited 2023 Dec 17]. Available at: www.dermnetnz.org/topics/infantile-papular-acrodermatitis-images

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.